There are a fair number of TBR-related sites still in existence. Of these, only a handful are regularly visited by tourists and then one is forced to query if those day-trippers even know why they are there.

As a way of documenting and preserving them, I present here a list of TBR-related sites in geographical order of their alignment. All but three are in the Province of Kanchanaburi and most are in the immediate area of Kanchanaburi City.

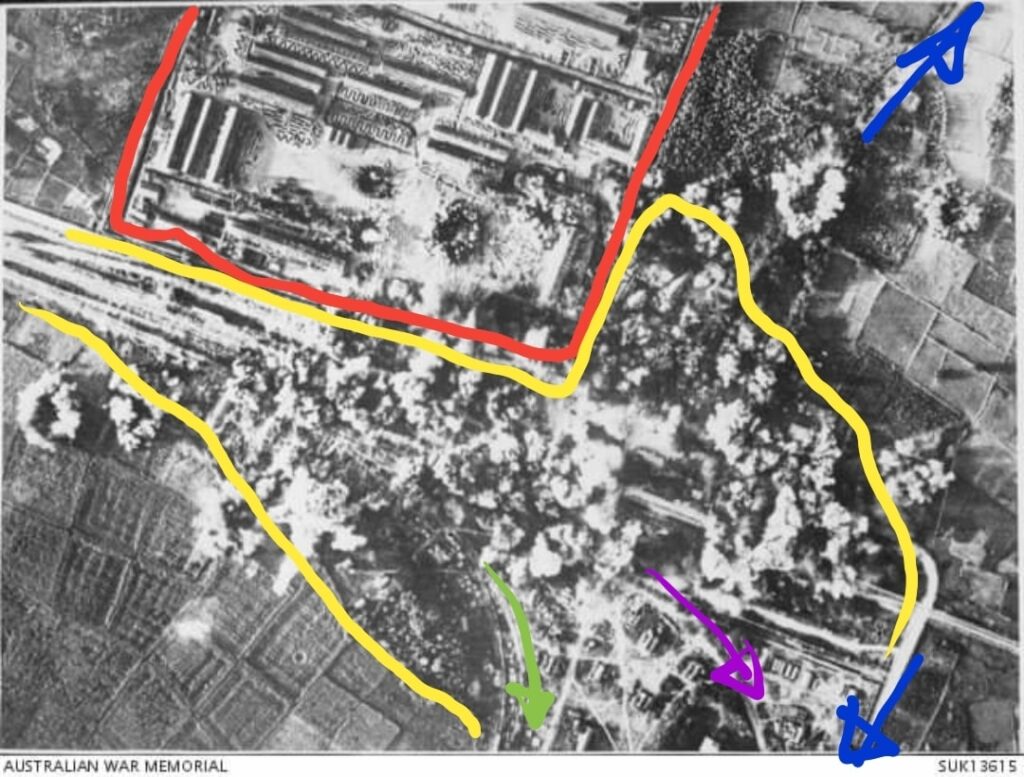

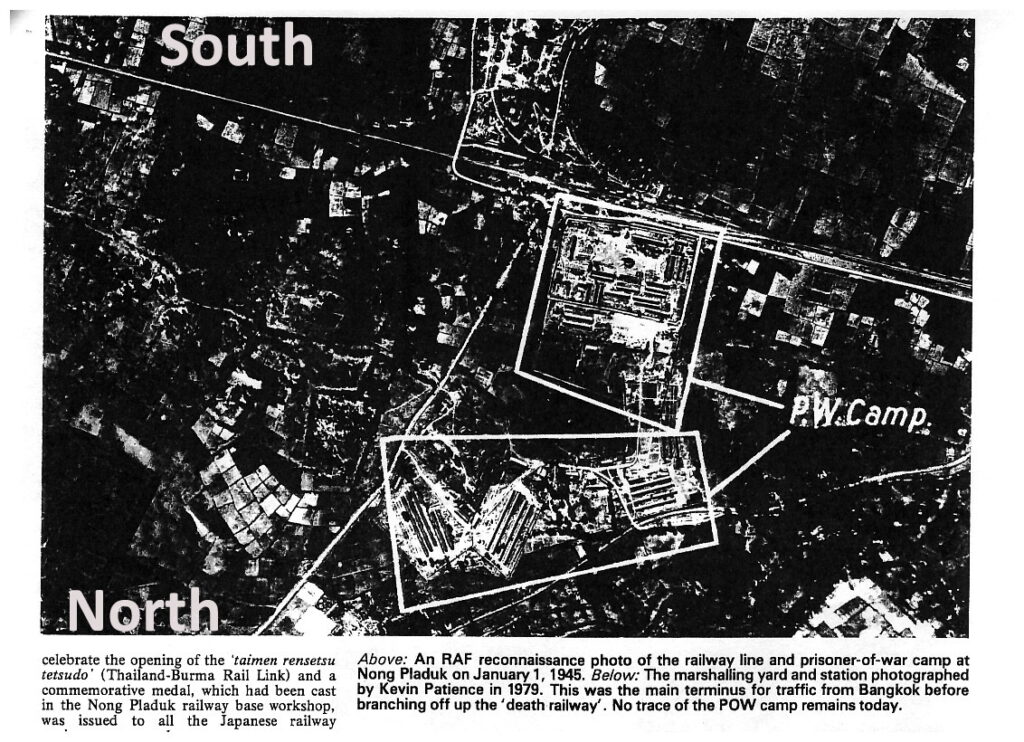

We begin at the beginning! Labelled as Nong Pla Duk Junction on maps, this SRT station is still a major maintenance center as it was in the TBR-era. One aspect that differentiates it from other TBR-sites is that it has a memorial stone erected by the Japanese to commemorate the beginning of the TBR in SEP 1942. Era recon photos clearly show the POW camp location to the immediate north of the rails. Just to the east is the location of the POW cemetery (next to the recently built fly-over).

Post-construction, a second POW camp was esastablished and many of the Dutch POWs were re-located there. It was just to the north of the original camp. Just to the south, in the area behind the local temple, are scattered remnants and artifacts of the TBR, all located on private land.

About three Kms west is one of the most poignant of all the TBR sites. Wat Dom Toom is located on the east side of the small city of Ban Pong. Here is the point at which the trains from the south carrying the POWs from Changi or the romusha from Malaya stopped to discharge their cargo. The open field in the middle of the temple grounds was the site of the transit camp. All new arrivals passed through the “gate to hell” to begin their TBR horror story.

Today, nothing denotes the location or the significance of this site. Among all the others, IMHO, this is the single site deserving of development as a major new tourist attraction. [see Section 11.7 for a more complete description of this site]

Simply because it is on the main road in line with the famous Bridge, the CWGC war cemetery at Don Rak is one of the most visited TBR sites. The signage describes the layout and contents of the cemetery but offers little more concerning its linkage to the events of 1942-45. [Section 11.4 describes this location]

Next to the cemetery is the Thai-Burma Railway Centre and museum. For anyone interested in the story of the TBR, this is a must visit! This is the single-most effective effort to relate the full story in its most realistic aspects. It requires a minimum of an hour (likely somewhat more) to try to absorb the huge amount of information imparted here.

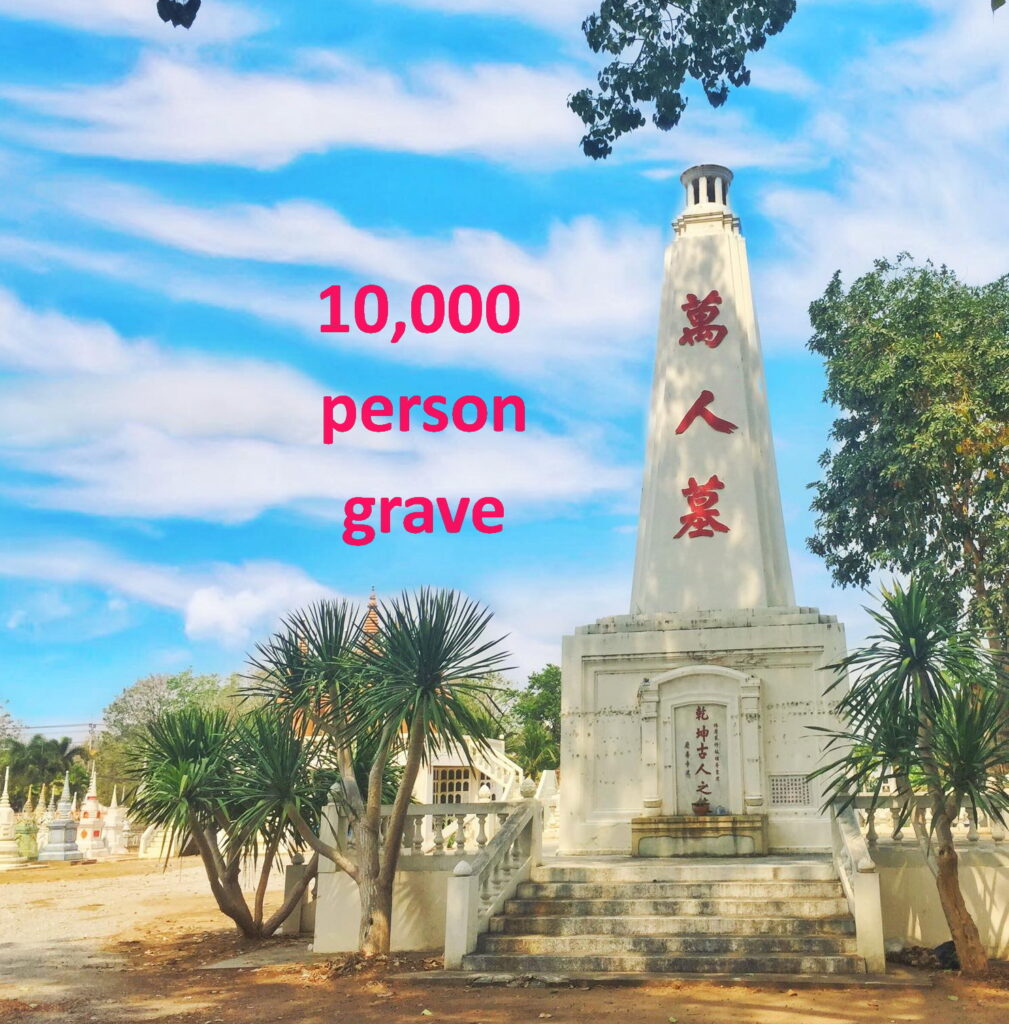

Immediately adjacent to this cemetery to the east is a typical Thai-Chinese family cemetery belonging to Wat Yuan. Located in its center is a most unique memorial obelisk labeled (in Chinese) as “Grave of 10,000 souls”. These are mainly Malay-Tamils who died in the immediate post-construction time (1943-46).

FEB 2024 Update: This memorial is in the process of being renovated and re-dedicated to the Tamil-Indians who are now known to be buried beneath it. The Malaysians and Indians in Bangkok (MIB) have opened a website to further tell the story of the Asian Forced Laborers at afl-mib.org

The primary destination of almost all tourists is the actual Bridge over the River Kwai. Despite the mis-labelling and general lack of knowledge of how this iron bridge is connected to history, it is visited by millions. Only a few know WHY they came! It is undoubtedly the focus of all TBR-related activity. The adjacent markets stalls, jewelry shops and restaurants draw huge amounts of revenue from the pockets of visitors.

TBR-era displays are located near the railway station where one can board the train and ride the restored portion of the TBR. Again, neither the display nor the railway provide much in the way of background information as to the TBR connection. There are, however, two tiny memorial markers that harken back to the TBR. One, to the left of the bridge, maps the path of the TBR and relates some basic statistics. The other was erected in 1997 to commemorate the contribution of the US POWs who labored and died on the TBR. [see Section 14.1]

A short walk east of the bridge is perhaps the most unique and most enigmatic of all the existing structures. This is the Thai-anusorn shrine dedicated in 1944, conceived by the IJA but built by POW ‘volunteers’. It is dedicated to the POWs and romusha who gave their lives in ‘service of the emperor’. Here, too, in this park-like setting opposite the City Hotel, nothing is displayed to make the link to the TBR and since the inscription is written in Chinese, the casual visitor usually fails to appreciate its meaning. This is another site that IMHO is ripe for future development – however ‘sanitized’ that story may need to be. Its story can be found in Section 14.3.

A bit to the southeast, next to Wat Chai Chumphon, is a museum named JEATH. This was actually the first and for many years the only site that attempted to link to the TBR history. It, too, is a must visit for anyone seeking a fuller understanding of history. [see Section 14.4]

Just a short distance from the original JEATH museum is a WW2-era site that is only indirectly associated with the TBR. The now-derelict Paper Factory was built in 1938 to make paper for the printing of Thai currency. It operated into the early 1950s, so it is contemporary with the TBR but is a site of historical interest in and of itself. (see Section 11.3) Similarly, near the current Railway Station is a display of a WW2-era locomotive. This, however, is not of a style that operated on the TBR itself.

Located not far from the preserved walled city gate, is the BoonPong house. This is a family-run museum that preserves the memory of Khun BoonPong and the smuggling operation he ran to provided vital items to the POWs. Not much English is spoken here and few visitors find their way to this unique place. His story is related in Section 11.2.

Nearer the bridge is a second site that had adopted (stolen?) the name JEATH museum. This is a third-rate attempt to separate tourists from their pocket money and is best avoided. The only item in the entire museum that can be directly linked to the TBR is a display of a glass case of human remains in this for-profit establishment! Give this place a miss!

Those who chose to ‘ride the rails’ of the restored portion of the TBR often detrain at the west end of the WangPo trestle. This is the second-most photographed portion of the actual TBR. There is a small market that caters to the tourists as they await the return of the train from Nam Tok (aka Tarso) to ferry them back to the Bridge.

The second site overseen by the CWGC is the cemetery at ChungKai. This is located across the river from the other sites near the point where the Kwae Noi River joins the Kwae Yai, opposite the old walled city. This cemetery marks the eastern boundary of a large POW camp that served many purposes over the course of the TBR build period.

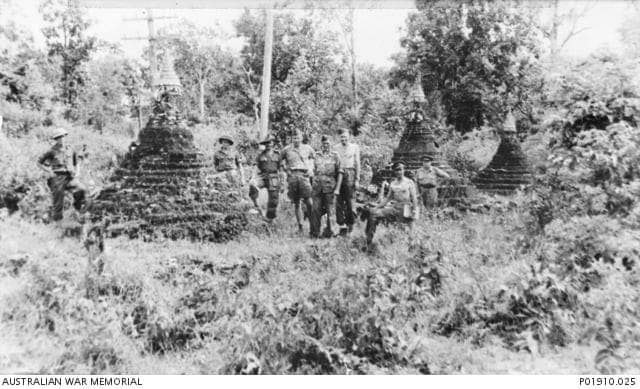

Proceeding west beyond ChungKai one can enter Wat Khao Poon. At the river’s edge one can descend a rickety set of steps to the level of the railway. You will find yourself standing between the first two of many ‘cuttings’ that were chopped and blasted through limestone that blocked the path of the TBR. These are the most accessible of any. [Section 8.5] Also see the entry below concerning the Khao Poon nearby caves.

Drone footage courtesy of Dan Manners:

The most infamous of these ‘cuttings’ is HellFire Pass. Located some 80 kilometers west of the Bridge, this is not as well-known nor as oft visited. It is however quite unique in that it is operated by the Australian government as a memorial to those who labored and died to build it. The POW contingent that labored here were not exclusively Australian, their numbers were dwarfed by the romusha workers. [Section 8.7]. Although the rails no longer exist, a portion of the TBR trace has been reclaimed from the jungle as a hiking trail.

Fifty kms farther on, is Wat PuThaKhian. On the grounds of this small temple are preserved a short section of the TBR. It is thought that this is the only place where any original sections of the rails exist although this is disputed by some.

Between these two sites is the Sai Yok waterfall park. Here, too, a WW2-era (not directly TBR) locomotive is on display. If one looks carefully it is not hard to find the remains of the trace as it curves out of the park, crosses the current highway and swings westward.

The last TBR-related site in Thailand is an ancient one. It was historically one of the main crossing points of armies and merchants between Siam and Burma. This is Three Pagodas Pass. This was the point of highest elevation of the TBR and where it crossed into Burma. Only a small section of preserved rails marks any association with the TBR.

Apparently the only sites in Burma that have a preserved association with the TBR is the CWGC cemetery and the museum at Thanbuzayat. It near the site of the Burma-side start point of the project. This small museum that makes an attempt (however feeble) to relate the story of the TBR. Unfortunately, due to political issues and lack of infrastructure, this site is inaccessible to even the most hardcore TBR aficionado.

In summary, there are roughly two dozen sites that a true aficionado may seek to visit to gain a better appreciation of the complete story of the TBR. But no physical site can convey the horror and inhumanity of the journey that the builders endured.

If you are tempted to visit the caves at Khao Poon I offer two warnings. The descent is a long, slow, leisurely walk. However, at about the lowest point the path narrows to barely a crack in the rock. Most adults need to side-step through. If you are blessed with a bit of extra weight, you may not make it past this choke point — which is perhaps a good thing, because the exit is via a seemingly endless set of nearly vertical steps that will tax your heart and stamina! Jump to 7:00 to see the exit stairs.

The exit path is seen at 15:00 in this vdo. Also at the beginning he tours the two cuttings.

0.2a A slightly different version

Except for the famous Bridge, there is not much in the way of physical evidence that the Thai-Burma Railway (TBR) ever existed. Most of the original iron sections of track were recycled to other parts of the State Railway of Thailand. The track, ties (sleepers) and ballast have all been replaced in the ensuing decades (almost a century).

The repaired iron bridge stands as a silent memorial to the thousands who labored and died on the TBR. But even there, only 2 tiny monuments tell anything of the history of the place. Most tourists, foreign and domestic, are loathe to cite any facts about the Bridge or the Railway as a whole. It is truly a piece of history that is being lost in the fog of time, if not war. And no one seems to care!

The single group that is dedicated to telling the story of the TBR is the staff of the TBRC = Thai-Burma Railway Centre. [https://www.tbrconline.com/ ] Rod Beattie and his crew have done an amazing job of telling the fullest story available via many different styles of displays and actual artifacts. It is located immediately adjacent to the main war graves cemetery in downtown Kanchanaburi. In one to two hours, visitors can learn the basic saga. But it would take multiple visits to absorb it all.

Of course, the most poignant reminder of the events that transpired from 1942-45 is the Don Rak cemetery’s nearly 7000 graves of those who perished working this project. In all, the three Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries hold over 12,000 such graves. But this is far short of the actual number of deaths that occurred. Other TBR-related deaths occurred in Japan, Vietnam and Singapore where men were sent along with the maladies they contracted while working the TBR. Nearly 300 men are interred in common graves having been cremated during the cholera outbreak. There are also a considerable number of POW remains that were never recovered. Except for a few dozen Dutchmen, they are not commemorated here. TBR survivors who died en route to new assignments when their Hellships were sunk, are commemorated elsewhere and not necessarily identified as being associated with the TBR. The less visited companion cemetery at ChungKai holds nearly 1700 more sets of remains. And another 3600 are in the third site in Burma.

In addition to these 12,000 recovered and commemorated men, tens of thousands more Asian Forced Laborers remain in the jungle without a memorial. Recently, a group of Tamils and Malaysian-Indians have rediscovered a tomb that likely holds over 10,000 of their ancestors. But these died after construction was finished. Those left in the jungle have no headstone of any sort. Hopefully, soon this group can rectify that wrong!

Perhaps the second most recognizable site is the viaduct at WangPo. Many confused tourists still think that this is the ‘original’ bridge and that the iron structure they just rode the train across is a ‘replacement’. Such is the level of knowledge and confusion over the true TBR story.

One of the oldest sites in town is actually rarely visited by any of the tourists that flock to the nearby Bridge with its jewelry and souvenir shops as well as an ersatz museum. The Thai-anusorn Shrine was built by the POWs themselves but the concept originated with the IJA staff. It commemorates those who died – both Allied and Asians – while ‘serving the Emperor’. Its story is too enigmatic and convoluted to relate here but it stands, generally unnoticed, in a quiet park about 150m from the Bridge.

For a number of reasons, I personally hold in great disdain the business that represents itself as a JEATH museum. Not only did it steal the name JEATH from the original museum (dating back to 1977), but it has the audacity to display the remains of over 100 of the Asian Laborers mentioned above in this for-profit enterprise. To make matters worse – if that is possible – 99% of what is displayed in that building has nothing what so ever to do with the TBR! They display a replica of the original wooden bridge, but if one looks closely enough it has a concrete base.

Beyond just strolling across an old bridge, and possibly stopping to look in on the cemetery that they pass on the way there, comparatively few tourists visit any of the other possible TBR-related sites. This is likely because they are either on a guided tour or on a personal day-trip three hours drive from Bangkok and want to get home before dark.

Other than the TBRCtr, the most informative place to go is the original (1977) JEATH museum located on the river bank in the old downtown area of Kanchanaburi city. Those who take the time to tour it cannot help but come away moved by the experience and with a bit of knowledge of the TBR saga. Since this museum is operated by the temple next door, it is technically not a for-profit business. It can be adequately – if hurriedly – toured in under an hour.

In their rush to get to and from Kanchanaburi, all the tourists drive past two other sites that no one but true aficionados of the TBR have even heard of. At the east-end start point of the TBR at the NongPlaDuk railhead, there stands a stone marker citing the place and date of the initiation of the project. The first POWs to arrive in Thailand from Singapore in June 1942 were housed at a camp there. Today, that site is a huge sugar cane field. On an adjacent field is the site of the POW cemetery. One has to know where to look to even remember what happened here.

For the first three kilometers the TBR track run parallel to the pre-existing line coming up from Singapore and Malaya. At the point where they diverge stands the Buddhist temple of Wat Don Toom. The trains arriving after their 3-5 day journey from the south would discharge their cargo (they could hardly be called passengers) in the small town of BanPong. A squalid transit camp existed on the grounds of this temple. Tens of thousands of POWs and hundreds of thousands of Asians were introduced to the TBR in that camp. They were generally happy to leave it behind, only to find much worse awaiting them. First, they had to trek 150 to 300 kms just to get to the place where they would live, work and die. Again, for me personally, this place holds the deepest of meaning. Only 39 US POWs passed through those gates. All the others arrived in Burma by ship, not train. But those 39 were have some of the worst experiences of all the 700 Americans who worked the TBR. Here, too, is a tiny and almost unknown memorial to some of the Japanese soldiers who died during their time in Thailand. We are led to believe that about 1,000 of the 15,000 or so Japanese troops died of disease or in the frequent Allied bombings.

The next site I will mention is only slightly harder to access. It is about a half-kilometer section of the TBR located just west of the ChungKai cemetery. The British POWs, many of whom were officers, that were sent to this first actual work camp laid the track from the bridge, then they moved dirt to make a 10m high berm to level the ground at the river bank before making the first two of dozens of cuttings through limestone obstacles that the TBR required. Beyond those, they built a moderate-size bridge still today called the Officer’s Bridge. With only slight physical exertion, one can walk into those cuttings and see a few of the holes chiseled in before the rock was split away.

The other place where one can feel the presence of the workers is at HellFire Pass. This is about an hour’s drive beyond the Bridge and at the 150 Kilo point of the TBR. It takes considerably more exertion to walk this path. There are 100 or more steps descending from the museum on the bluff down to the Kunyo Cutting as it is officially named. This is the first documented place where Asians labored in large numbers alongside mainly Australian POWs to chop away the 75 x 25 m outcropping. It is said that many men were beaten to death in the few weeks that it took to make this cutting. Today, the Australian government has adopted this as their official remembrance site.

Beyond this point there are only scattered remnants of anything to mark the path of the TBR. Man and Nature have reclaimed almost all traces that it ever existed. Almost anyone with a metal detector and the stamina to hike the jungle can still easily find artifacts. Too bad there is not a ‘bone detector’ of the same ilk. In 1991, hundreds of skeletons of Asians were excavated in the city. Out in the jungle, thousands of remains lie unburied and unremembered.

LEST WE FORGET.