BoonPong was 36yo when the Japanese arrived in Kanchanaburi. He and his family (6 siblings and extended family) lived in a set of three contiguous shop houses within the walled city and just a few hundred meters above the busy docks area at the point where the Kwae Noi and Mea Klong rivers met. Just up the road was the governor’s mansion.

His father, Khun Mar Khien, was a renowned physician and herbalist. One of the shops was his office and a pharmacy. Out of the others, the family ran a thriving trading business. If you wanted it; they’d supply it. Everyone knew the Sirivejjabhandu family. BoonPong himself was the town mayor at the time.

Of course, the people of Kanchanaburi were aware that the Administration of Prime Minister and Field Marshall Phibun Songkhram (ironically ‘songkhram’ in Thai = war) had capitulated to the Japanese. Just after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, they landed an army in southern Thailand that quickly marched across the Malay Peninsula and took control of Singapore (15 Feb 42). At the same time, the IJA landed a small force at Samut Prakan and demanded to see the Prime Minister.

Holding Saigon, Singapore and Burma, the IJA literally had Thailand surrounded. What military forces Thailand maintained were mostly on the north (Chiang Mai / Chiang Rai area) guarding the Sino-Burma border areas.

It wasn’t until about AUG 42 that the first IJA troops arrived at the walled city of Kanchanaburi. Again, the small garrison of Thai troops at Lat Ya guarding the traditional Burmese route of invasion were no match for the 1000 or so IJA engineers and support troops that were preparing to extend the railway to Burma. It had only taken the IJA engineers and their mostly Thai workers a matter of weeks to lay the 50Km of rails from Nong PlaDuk to Kanchanaburi. Now the IJA support troops were there in force to support the push across the river.

Needless to say, they needed supplies. They were quickly pointed to the Sirivejjabhandu family business and they were contracted to provide basic necessities. Life was good for all concerned. Over time, Kanchanaburi became a major HQ of the IJA troops supporting the building and then operation of the TBR.

But the town’s people were shocked and appalled when LtCol. Toosey’s group of British POWs was marched past the town walls and up to Thamakam where they would eventually build a bridge. It was NOV 1942, the Japanese soldiers had been in the area establishing a HQ and supply depot since about AUG. But the arrival of rather bedraggled POWs was a shock to all who saw them. A small group of British POWs under the command of Major John Roberts of the 80th Tank Regiment had preceded them and built the camp where they were to live.

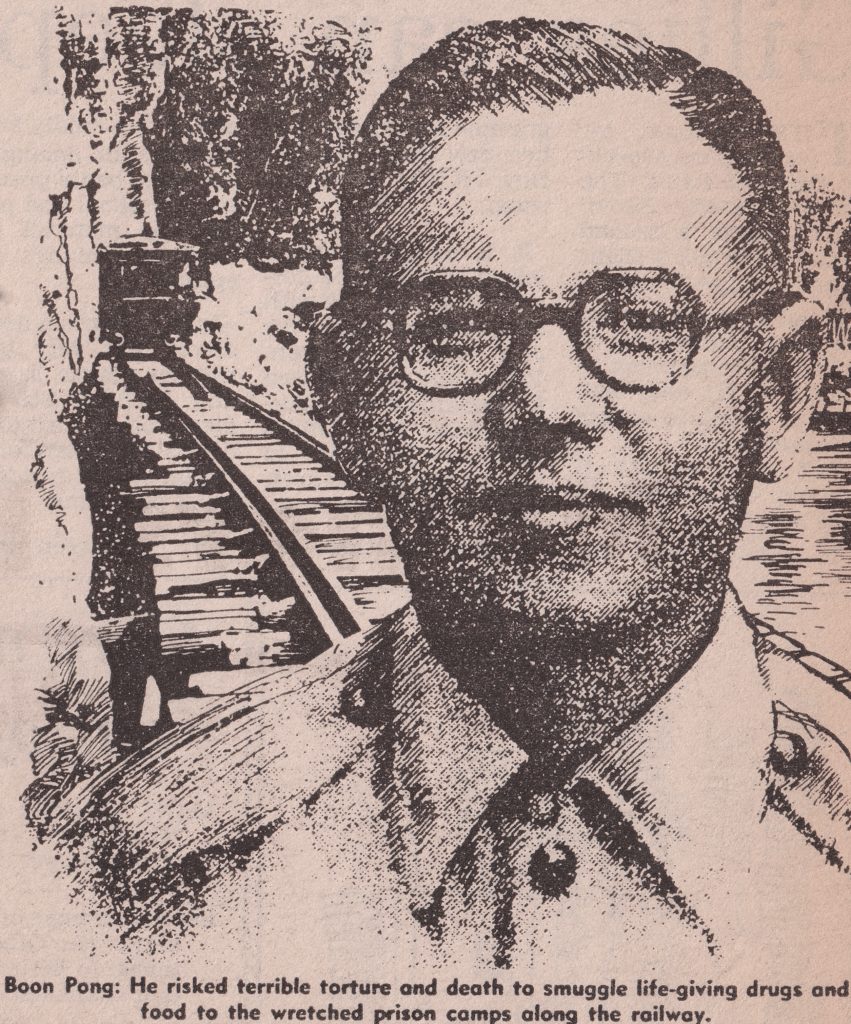

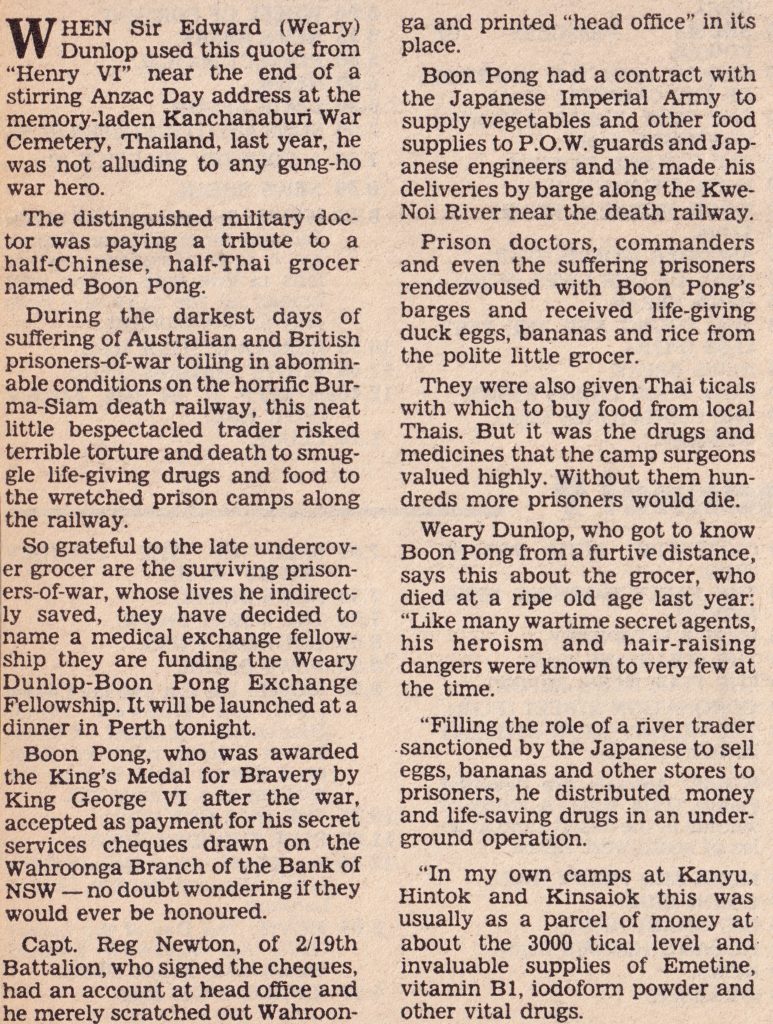

As the work on the Thai-Burma Railway began in earnest, more and more POWs and native Asian laborers were moved through Kanchanaburi to camps in the jungles to the west. The Kwae Noi river was the major route of movement of men and supplies. The Japanese authorities awarded the Sirivejjabhandu family more contracts for goods of all types; supplying various staples and some food items like fresh vegetables, eggs and fruit. Part of the contract apparently included logs and/or finished railway ties (sleepers). Khun (Mr. in Thai) BoonPong took the lead in delivering those supplies by boat along the Kwae Noi River. One of the camps that he frequently visited was that of the largely Australian H-Force commanded by LtCol. E. “Weary” Dunlop in the Hintok area nearly 100 kilo upriver from KAN.

He was deeply moved and appalled by the condition of the men in that and other camps where he took supplies. He managed to establish a working relationship with LtCol. Dunlop and a handful of other POW leaders, including LtCol. Toosey. They formed what became known as the ‘V Organization’ or sometime the ‘V Men’s Club’. [see Section 15.2 for a more detailed discussion of this group] Over the course of the period of labor on the TBR, Khun BoonPong, his wife, daughter and sister, at great risk to themselves smuggled desperately needed items to these camps. Some of the most cherished items were drugs which the Japanese refused to supply to the POWs. Since he had a physician father and also a pharmacy, procurement was not an issue; delivery was. One of the contracts the family had was to supply ‘consumer goods’ to small canteens that the captors allowed the POWs to have access to. BoonPong provided things like tobacco and sugar. They would conceal the contraband in the items being delivered and apparently through some secret coding method would mark those packets so the POWs-in-the-know could extract those items. This was the primary method that ‘prohibited items’ like medications and medical instruments, as well as cash, were passed to the POWs. He was able to involve others — pro-British businessmen in Bangkok in particular — who provided cash currency that was smuggled to the camps to allow for the purchase of extra food or whatever was available from local villagers. Khun BoonPong’s wife, Surat, his sister, and daughter were often involved in the exchange of bundles of cash or coins to the POWs.

He dealt with a number of the POW commanders including LtCol. Toosey but his relationship with Dunlop was the strongest. Dunlop (a physician himself) credits Khun BoonPong with saving many POW lives at the risk of his own for the smuggling. Soon after the war, BoonPong was shot and seriously (nearly fatally) wounded. Dr. Dunlop used his considerable influence from Australia to get blood flown in to save BoonPong.

As I write this essay in early 2021, the Sirivejjabhandu family dwelling is open as a private museum. Awaiting your arrival is the single surviving member of the family who knew and lived with Khun BoonPong. She is the wife of his youngest brother and is 90+ years old. She relates one episode of this saga in that the Japanese left behind some 200 trucks. The family managed to ‘secure possession’ of them and BoonPong had them modified and began a bus service from KAN to BKK and in the KAN area. Apparently, this start-up was partially funded by donations from former Australian POWs led by Dunlop.

Khun BoonPong died in his beloved state of Kanchanaburi on 29 Jan 1982. He was awarded the George Cross and made an MBE [Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire] and the Orange-Nassau by the Dutch. Khun BoonPong’s story is not widely known, his heroic efforts are mainly recounted in POW survivor accounts of their experience. The Thai PBS network also made a mini-series a few years ago, recounting a fictionalized version (and somewhat sanitized as far as the treatment and condition of the POWs is concerned) that is available on YOUTUBE:

https://pows.jiaponline.org/2019/01/honoring-thai-hero.html

Also see https://2nd4thmgb.com.au/story/boon-pong/ which includes this story:

More from that site:

There is no doubt without the assistance and bravery of this man, many more hundreds of POWs would have died. He managed to get messages, medicines, money and contraband to several camps. His wife was also his accomplice, assisting him whenever she was able. She would entertain Japanese soldiers who visited her store while her husband talked with Camp doctors and leaders who managed to persuade the Japanese guards to drive to Kanchanaburi for supplies. Boonpong’s wife had learnt a little Japanese from her Japanese neighbour.

Boonpong was contracted by the Japanese to provide supplies to the railway workforce. It was during his delivery visits to work camps along the river/railway Boonpong was to see for himself the horrific conditions the POWs lived in.

He began to secretly work with a resistance group based in an internment camp Bangkok – the ‘V’ organisation, the source of BoonPong’s cash and drugs.

In early 1943 Boonpong acted as intermediary between the ‘V’ organisation and POWs. Most British civilians were interned in the Vajiravudh College, Bangkok. These included Mr. Peter Heath, Chief Officer of the Borneo Company involved in shipping and commence, Mr K. Gairdner of Siam Architects Imports Company and Dick Hempson of the Anglo-Thai Corporation importing business. Gairdner’s Thai wife, Millie was free to move about and soon learnt of the plight of large numbers of British POWs who had been working on the earlier stages of the rail construction – prior to Australians or Dutch.

Initial efforts had been paid for personally by group, but realising the magnitude of what was ahead, it was decided to raise funds from the general business community.

This was the beginning of what would become known as ‘V’ Organisation, later becoming two groups both names ‘V’.

Heath and Hempson later stated “Money was therefore raised from persons outside the Camp under guarantee of repayment in sterling after the war. The guarantees were originally signed by persons of standing within our camp or known to be possessed of means.”

Attempts were made through the Red Cross to contact the British Government to inform them of the POW’s plight and to obtain pledges of financial support for the reimbursements of all moneys raised after the war.

Four Railway Camps assisted by ‘V’ Organisation with considerable amounts of money (English Pounds) included No. 4 Group Base Hospital Camp Tarsau – 2,400, Tamarkan – 2,800, Tonchan – 933 and Tamuang – 1000.

The organisation included many foreign and local business owners who were able to raise large sums of money on loan. Millie was one of those who risked passing money and drugs directly to POWs via the many POW lorry drivers.

Amongst those Boonpong had personal dealings with many POWs. Included were Capt Reg Newton, 2/19th Btn who headed up D Force U Battalion, Colonel Toosey of Tamarkan, later Weary Dunlop and others. Boonpong as a Thai river trader and supplier to the Japanese first made contact with Colonel Toosey at Tamarkan. So began a system of smuggling aided by his daughter, to provide much needed medicines.

Boonpong’s barges eventually operated from Bampong to Takanun and during the wet season as far north at Neike.

Boonpong had personally lent his own money during the war (cashing POW cheques, lending money on watches etc to be redeemed after the war) that by 1947 Boonpoong was found to be in financial difficulties. A POW organisation raised funds and at least one British Division Association in response to Col. Toosey’s request donated nearly 40,000 pounds to enable him to set up a bus company in 1948.

Businessman and former mayor of Kanchanaburi from 1942-1945, Boonpong died January 1982 aged 76 years.

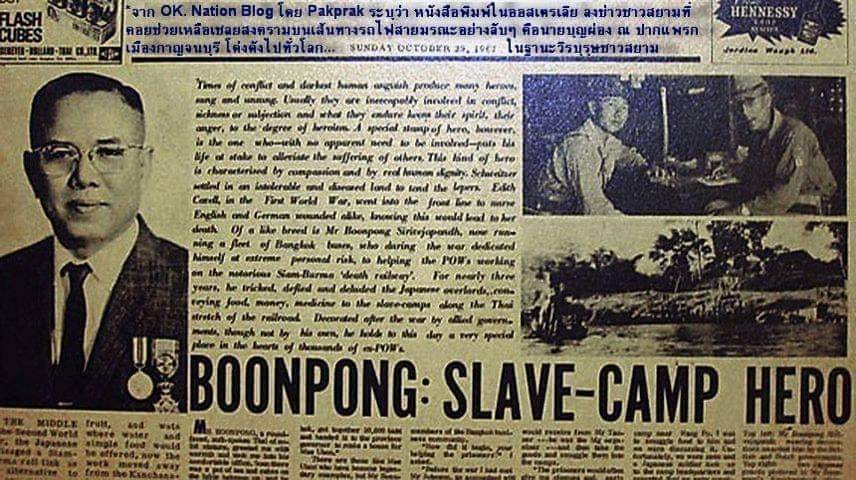

After the war, little was known in the outside world of Boonpong and his role.

Thai newspapers reported that in 1948 he was awarded the MBE by the British and Orange-Nassau by the Dutch.

In his 1985 address on Anzac Day at Kanchanaburi Weary Dunlop paid tribute to Boonpong and other Thais who had assisted POWs. In 1986 a Fellowship was established – a collaborative programme between the Royal Australian College of Surgeons and the Royal College of Surgeons Thailand providing Thai surgeons opportunities for surgical training attachments at Australian hospitals.

In 1998 the Australian Government at opening of Hellfire Pass Museum formally recognised the bravery of Boonpong, presenting his grandson with a Certificate of Appreciation for the ‘unrepayable debt’ owed to his grandfather. $50,000 donation was made to the Boonpong-Weary Dunlop Exchange Fellowship.

One cannot begin to imagine how many more hundreds, perhaps as many as a thousands of lives would have been lost without the efforts of the ‘V’ organisation and Boonpong.

That 2/4 MG site also displays 2008 photos of the old city of KAN:

Also a 2008 Australian movie “The Quiet Lions”:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1262946/

The booklet provided by the Sirivejjabhandu family museum mentions the following names as being part of or contributors to secret V organization. They are Kenneth G Gairdner, R D Hamwim., David Hempson and Peter E Heath. I could only find the merest mention of Heath via an on-line search. Researching their stories could be a life-long quest in the darkness. Kenneth and Millicent Gairdner were real people who left a significant electronic footprint. Millicent was not Thai; her maiden name was DeSilva and she was born in Cambodia likely to diplomat or business man.

An interesting Bangkok Post article:

https://www.bangkokpost.com/travel/369279/echoes-of-a-storied-past

Purloined from Green Writing Room Hilary Custance Green’s reading and writing notepad:

https://greenwritingroom.com/2014/01/12/boon-pong-and-other-forgotten-heroes/

Tucked into one of the books on Barry’s shelves about Far East POWs was a little photocopied leaflet of 1998, being re-issued for ‘X’mas 2000’. It starts:

I am one of the persons who had seen the event about the railway construction from Kanchanaburi to Myanmar during World War II when I was 19 years old, 1941. As a saleswoman at Khao Chon Kai (Chungkai) War-prisoner Camp.

“Her name was Lulu Na Wanglan and she tells her story, explaining that even after 50 years, ‘I dreamed of those war-prisoners before I started to wright.’. She supplied prisoners until she had ‘no more capital to trade or sale goods.’ At this point she was given some money, probably by the local underground, to continue supplying prisoners. She was suspected of spying by the Japanese and was warned by Mr Boon Pong in time to escape. The prisoners thought she had been shot (confusing her with a brave French spy, ‘Lulu’ who had been killed by the Japanese) and they missed her. After the war, UNO staff painted Lulu on their vehicles. Prisoners remember her in their memoirs.”

Boon Pong (Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu) was a Thai trader whose sympathies were aroused by the state of the prisoners. In early 1943 he became the interface between the V organisation and the prisoners. The ‘V’ organisation was run by an interned British man, Ken Gairdner, with a Thai wife, Millie, and many free business connections. Many others (Peter Heath and Dick Hempson) were involved and as the prisoners’ conditions worsened they raised large sums of money on loan. Millie was among those who dared to risk passing money and drugs directly to prisoners via the many POW lorry drivers.

The upriver camps had almost no supplies of medicine and very little food, especially higher up-river where barges could not go. Conditions became dire beyond imagining and their only source of relief was the money and drugs that Boon Pong managed to get to them, acting always as a legitimate trader. He also obtained and supplied ‘Canary Seed’ (radio batteries), if the Japanese had discovered this he would have been tortured and killed. There were other traders, but his prices were lowest. He worked the length of the river, but after the railway was complete and the men poured down-stream in vast numbers to the big base ‘hospital’ camps, his role became even more crucial in saving lives with supplies of food and medicines and even violin strings.

In a story by Brian Brown of the Royal Signals in Beyond the Bamboo Screen (ed. Tom McGowran) he quotes another POW saying the Boon Pong’s wife swam their camp moat at night with medical aid round her neck. The effect on morale of the efforts by this family were incalculable.

Australian Surgeon and POW, LtCol. Weary Dunlop, kept a diary. 25 October 1943 reads: The hospital today obtained some most useful drugs and money *. The footnote reads: By grace of that magnificent man, Boon Pong. His entry 30 December 1943, A Valuable supply of drugs and 3,000 ticals [this was due to the wonderful services of Boon Pong, the river trader]. And so on.

In the aftermath of the war in September 1945, Boon Pong was shot outside his shop in Kanchanaburi in front of his wife and father. Julie Summers in her book about LtCol. Toosey, The Colonel of Tamarkan writes:

A British officer, …Captain Newall heard the shots and rushed to the scene. ‘He had been shot through his neck and left arm and he had also been shot clean through the back. There was a large hole in his chest where the bullet emerged and spent itself. He looked up at me. “Thai police kill me.” That was all he said.’

A British medical team gave him blood transfusions and operated on his wounds and, amazingly, he eventually recovered. In 1947, Colonel Toosey heard that Boon Pong, now running a bus company, had got into financial difficulties.

Toosey asked fellow prisoners to contribute and they raised £38,000. Boon Pong’s company became successful and his sons now run it. He received the MBE in 1948. He is popularly supposed to have been awarded the George medal, but Clifford Kinvig in The River Kwai Railway, says there is no official record of this.

He died in January 1982 and in 1988 The Weary Dunlop -Boon Pong Fellowship – an Australian exchange fellowship for Thai surgeons, was set up soon thereafter:

Boon Pong is remembered in many memoirs and I have only given a rather scrambled outline here of his contribution to humanity. I apologize for any errors.

==========================================

I do not think that this is typical, but here is the camp itinerary of a British POW:

He left Singapore OCT 1942 and was attached to Group 4 (19 (Bridge Bn)

His work camps and distance from the start of the Railway at Nong Pladuk

1 Tha Makham 56.2 Km under Lt. Col. Philip Toosey 135 Field Regiment

R/A. Oct 42 – June 43 [likely participated in the building of the wooden bridge]

2 Kannyu 2 151 Km under Capt Douglas Viney 135 Field Regiment R/A. June

43 – August 43

3 Tha Khanun 223.4 Km Capt Douglas Viney August 43 – November 43

4 Tha Sao (Headquarters of Group 4 until moved to Tha Muang in mid 1944)

125 Km under Lt. Col. Alfred Knights 4th Bn. The Royal Norfolk Regiment.

November 43 – June 44

5 and 6 Konkoita 262.53 Km and Kree (Kri) 192 Km. under Lt. Col.

MacKellar 88 Field Regiment R/A. June – October 44.

7 Tha Makham 56.2 Km. under Lt. Col John Williamson 1 Indian H.A.A.

Regiment R/A. October 44 – January 45.

8 Phetchaburi not on the Railway (building an Aerodrome) Under Sergeant

(Lt) Ross Davidson 105 General Transport Company, Australian Army

Service Corps.

==================

A bit more on the history of the Seri Thai:

These are purported to be shots of barges use at Ubon, but they are undoubtedly similar to those Khun BoonPong would have used on the Kwae Noi river:

Here’s another version of his story as posted on the internet as translated from Thai:

When I post these translations; I clean them up somewhat but do not fully edit them for grammar.

Boon Phong Sirivejchaphan…Hero of the Death Railway…….

The word “Thai kindness” seems to be the most appropriate for this matter. Even now you are gone but your name remains forever. with your great kindness for the prisoners of war at that time…..about ten years ago many moviegoers have seen Schindler’s List, the 1993 best Oscar film by renowned director Steven Spielberg, based on a true World War II era. When the German soldiers built a Jewish concentration camp to genocide the Jews completely. But a businessman named Childer who had good ties with Nazi officers I couldn’t bear to see the brutal massacre. Thus, he secretly saved thousands of Jews from being killed by smoke gas.

We also have an anonymous hero in our country during World War II. Rescue of prisoners of war from Japanese soldiers’ attacks in the construction of a railway crossing the bridge over the River Kwai Kanchanaburi but rarely anyone reveals his story to the society is a man named “Boon Phong Sirivejchaphan”. On the one hand, his business was known to the people of the capital thirty years ago. is the Boon Phong bus; a private bus company that has a concession to pick up passengers in Bangkok before the authorities seized the bus business as a state enterprise later. But it seems that Boon Phong’s name is well known among the Allied nations. who remember his merit more than Thai people.

In 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army decided to build a railway linking Burma and Thailand to transport troops and weapons. The goal was to successfully invade Burma and India in a short time. The Japanese army therefore recruited more than two hundred thousand Asian civilian workers [aka romusha] and Allied prisoners of war.

Most of Australians is caught in Singapore. More than sixty thousand Malaysians to complete a four-hundred-kilometer railway line within a year until it has been dubbed the Death Railway because the saying “One sleeper is one prisoner’s life” and Kanchanaburi is an important victory that the Japanese Army chose to build a railway.

A prisoner camp was built along the cutting path. Thousands of Allied prisoners of war suffered from sickness, hard labor, imprisonment, etc. But many prisoners of war survived through the secret assistance of many Thais who secretly helped deliver supplies and medicines to these prisoners in humanitarian manner. If caught by Japanese soldiers they may have been tortured or shot and killed. At that time, Mr. Boonpong Sirivejchaphan was the mayor of good standing in Kanchanaburi and lived on Pak Phraek Road, which is the commercial district of the city. He was also a Thai merchant, owner of Siri Osoth shop. Concessions were given to deliver food to the prisoners’ camps all the way to the end of the Death Railway and auctioned off railway sleepers for sale to the Japanese soldiers as well.

At that time, Pak Phraek was an important trading place is the source of goods that are closest to the barracks and Boon Phong had the advantage of other shops that can speak English and communicate well with Japanese soldiers and prisoners of war. Therefore, it was entrusted to enter and exit the prisoner of war camp. From a merchant career that started from selling products only, but when he got to know the suffering and suffering of prisoners of war in the camps, especially malaria patients. There is not enough quinine to cure the patient. Every day, sick people died and their bodies were thrown into the river. And finally, Boon Phong received a request for help from Dr. Weary [Dunlop]. Australian surgeon for humanitarian reasons. So he risked his life to smuggle quinine to Dr. Weary to cure his surviving patients regularly. Sometimes food, medicine and utensils are hidden in the vegetable baskets to be given to prisoners of war, mostly Australians. England and the Netherlands. Many times he had to sneak into the camp at night with items around the neck hanging medical supplies and later to Ms. Panee and their ten-year-old daughter secretly brought pills to the prisoners of war so that the Japanese would not suspect them.

In addition, Mr. Boon Phong is also a secretive contact with prisoners of war. Helped send secret documents indicating the bridge’s coordinates to the Allies many times until the Allies dropped bombs on the bridge over the River Kwai accurately. Aunt Lamyai, Boon Phong’s [surviving] sister-in-law, once said that “The bridge is in the forest in the grove. who is going to see at that time”, I believed that Boon Phong had to be the part that caused the bomb to land in the right place.

”Sometimes many prisoners of war had no money. Boon Phong gave the prisoners a loan to buy things according to John Coast, a former British prisoner of war who recorded that “The prisoners are thin. Lack of food and no money. He gave loans with items such as watches, rings, or cigarette packs as collateral. We still don’t trust him very much. but time proves he is truthful in every word. He returned his belongings to everyone who redeemed them. ”Finally, when you Surat (Boon Phong’s wife) knows the story. There was a serious quarrel in the family. One party does not want the family to be in danger. But the other side sacrifices to save people from dying in front of them. Even having to bet on life with family, wives, daughters and everyone of Sirivejchaphan’s family.

Until the end of 1944, the world war was nearing its end. [editor’s note: this happened post-war not in 1944]. The Japanese army is losing every battle. Boon Phong was shot in the city and was wounded. which was assumed to be from people who were dissatisfied with Boon Phong helping prisoners. Later, Dr. Weary had recorded that Boon Phong survived the shooting. The bullet went through the chest. But with the best efforts of the former prisoner of war’s medical team, it was closely supervised.until Boon Phong escaped the danger.

He lived for a long time until he came out to do business on the Boon Phong buses. With the help of Allied soldiers to collect 200 trucks seized from Japanese soldiers. Let him come to the bus business in the capital in the year B.E. 2490. [1947], After the war, former foreign prisoners and foreigners hailed him as the hero of the Death Railway, who thousands of foreigners insisted that “they owe him a lifelong debt of gratitude to Mr Boonpong. It’s a debt… that can’t be paid back!!!

”In 1948, Mr. Boon Phong was awarded the Royal Order of the Australian Government. England and the Netherlands and every Christmas he and his wife received many congratulatory letters and gifts from prisoners of war. and Queen Elizabeth II and her husband. On his visit to Thailand in 1972, Boon Phong and his wife were ordered to attend and join the dining table. and was decorated with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel Boon Phong of England and the Netherlands.

Until on January 29, 1982, the news was published in the newspapers of England, the Netherlands and Australia reported that Thai World War Hero died of Coronary Heart Disease Several former veterans were interviewed. Praise the bravery and keep them alive because of this Thai man. In 1998, on the opening day of the Hellfire Pass Museum to commemorate the Allied prisoners of war who died during the construction of the Death Railway, the Australian government, headed by Prime Minister John Howard, has also formally declared Boonpong’s courageous memoir by a certificate admitting that they owe Mr Boonpong. By giving to many men Mr. Boon Phong and specify in the declaration “May this certificate be a mark of gratitude for the virtuous deeds of your ancestors and to symbolize the warmth of our friendship which has grown steadily since the war. During the life of a person who has lived for many decades others will remember our lives only at certain critical moments. How will one person’s life be remembered by others? We have the right to choose.

Information: documentary.com via Sakon Ketkaew.