A proposal for a new memorial by a colleague and fellow TBR aficionado, Thansawath Saranyathadawong:

Translated into English from his original Thai post.

An excavation in Kanchanaburi in 1990 found about 500 skeletons of Asian workers who came to build the Death Railway. This article is a little long article, but I want you to please read it to the end.

In the most oft told story of the Death Railway, we can only see images of Western (Allied) Prisoners of War (POWs), thin to the bone. Their work was hard and they were subjected to violence by Korean guards and Japanese soldiers. Many thought that the railway could only be completed because of the sweat and life of a western prisoner of war.

But in fact, there were huge numbers of Asian laborers from many nations, including India, Burma, China, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Malays, Javanese, Indonesians, as well as local Thai workers. There were as many as 250,000-500,000 Asian laborers building the Death Railway of whom 30-50% died!

There are about 61,000 Allied POWs, which are actually many times less than the Asian laborers. But we also know very little about the story of the Asian laborers.

For reference, I use the New York Times as I wrote above.

Article on the World War II Cemetery in the book of Arts and Culture in February 1991 written by Khun Sathaporn Kwanyuen, an officer of the Department of Arts at the search point.

The book written by Ajarn Worawut Suwanrit Titled the Great War of Asia

and another set of foreign articles and documents from Landscape Kan, Pak Phraek area, written by Somchaya Thanangku

The number of deaths of Asian laborers is estimated at 90,000-100,000, or 40% of all Asian workers because of being crowded; lack of cleanliness; to say nothing of the lack of medication, insufficient food, and many diseases.

Turn around and look at the Allied POWs. The death toll was about 13,000, or 21% of all prisoners of war. The living conditions of prisoners of war were bad, such as not enough food, not enough medicine, hard labor but if you come across the story of the Asian laborers, you will know that the prisoners of war had better living conditions than Asian laborers. Prisoners of war were normally soldiers with knowledge of discipline and cleanliness; to prevent epidemic as well as in each unit was a military doctor. Therefore, these physicians are also able to advise or be able to design and modify existing ones into medical devices; including requesting to share medicines from Japan to treat the severely ill . Prisoner of war camps have better cleanliness management compared to labor camps. Separate camps were set up for various disease patients to prevent infection from spreading.

Therefore, it is not wrong to say that the Asian labor force is the main labor in the construction of this railway line.

Let’s get into the story about the discovery of a large number of skeletons of Asian laborers at the side of Kanchanaburi City Hall in 1990 or 1990. To begin with, it seems mysterious and difficult to answer. But here is how the story unfolded:

“One night, the owner of a motorcycle repair shop named Khun Sompong (a Wang Sai native) had a dream that he was standing in a sugarcane field.

There were many people in the sugarcane-free area. But the conditions of those people were all languid, starving, sick and wearing torn clothes. They looked pitiful, someone walked in and told them to come and help them to get free. In the dream, Khun Sompong recalled that there was a large stag (dead and devoid of foliage?) tree in the area as a landmark.

Khun Sompong tried to find the area of his dreams. So drove a motorcycle to search. When he arrived in front of Soi SangChuto 14, something inspired him to stop and ask the locals there. Khun Sompong asked if there were any burial grounds in this alley. The old man in front of the alley didn’t say anything, just pointed into the alley. So he drove to look and found that there was a sugar cane plantation and in it was a huge bare tree, as he had dreamed of. The area is located about 100 meters from the city hall wall and about 200 meters from SangChuto Road. [In the area of the large City Hall and near the huge hospital complex on SangChuto Rd.]

But when he found it, but Khun Sompong was still unable to do anything.

At that time, there are people from the Bodhibhavana Welfare Foundation to contact would like to buy the land of Mr. Sompong. So his wife took this opportunity to discuss the strange things that her husband had dreamed of and the places in his dreams that he had found. The staff of the said foundation gave advice that Khun Sompong contact the landowner, Teacher Ananya Wattanayam. for permission in writing to dig on her land.

At first, Teacher Ananya denied that she had never buried anyone. But her older sister insisted that this sugar cane field used to be a burial ground for a railway worker during World War II. She related [Bg 25pg19]: “when she was about 20 years old [1945] field hospitals for sick Indians, Malayan and Singaporean workers were located where the Kanchanaburi Provincial Hall is now. Every morning the Indians dug a hole to bury the dead bodies in the evening. The bodies were simply thrown into the pit and covered with dirt. Some days, 2-3 bodies were buried; some days more than 5.” Teacher Ananya agreed to sign a permit to exhume the body without asking for any compensation for excavating the field. Another neighbor stated [Bg25pg19] that: ”I saw Japanese soldiers digging huge graves into which bodies were dumped. Some were sick but still alive.”

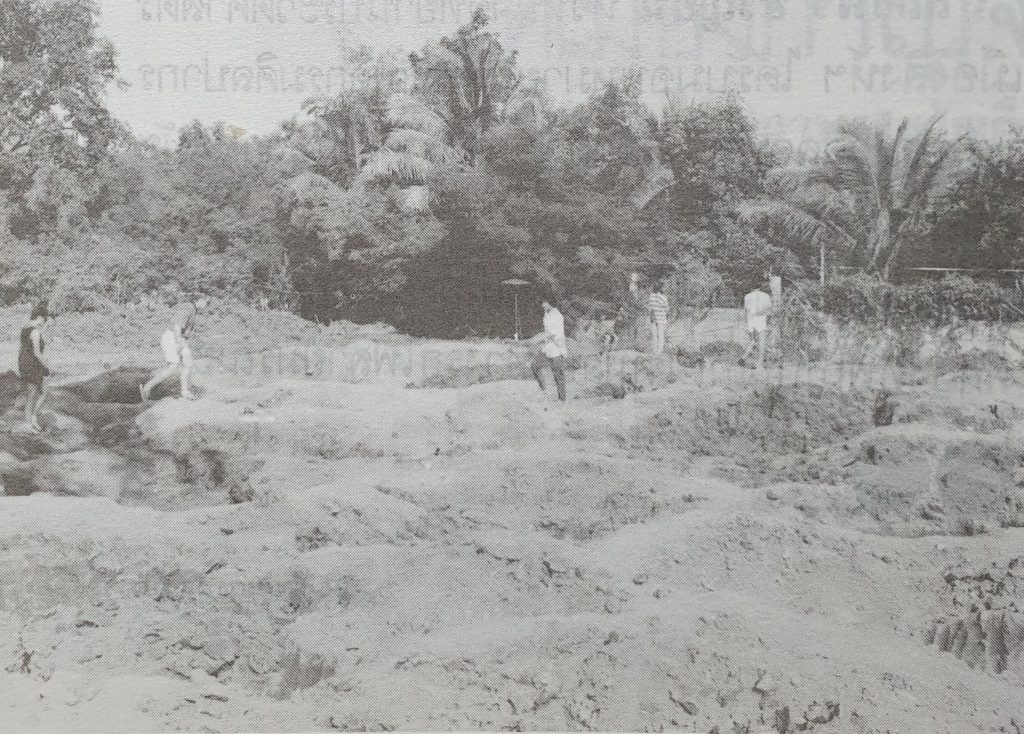

A tractor was loaned by Pol Lt. Gen. Chamras Mangalarat, to plow the area until the soil was ready to look for the skeletons to be dug up with a hoe and shovel.

Before starting the digging, the Bodhiphanasongkho Foundation held a ceremony for the dead. In the excavation, there will be a spirits and the medium pointed to the graves. Red flags were placed and excavations were carried out. Many people participated in this merit making ceremony.

On the 15th of Nov 1990, the first day of the exhumation hundreds of skeletons were found lying on top of each other in a hole. Also found were some a glass containers and a number of zinc-coated rice bowls.

By Nov 16, 1990, as exhumations continued, approximately 104 skeletons were found.

After news spread the Director-General of the Fine Arts Department came to inspect the excavation area. Seeing that this kind of digging may destroy historical evidence, he asked that they stop digging. A letter was sent to the governor Kanchanaburi and he ordered the foundation to temporarily stop the excavation handed the project over to the Archeology Division Muang Sing Historical Park led by Khun Sathaporn Kwanyuen and with Ajarn Worawut Suwanrit, Secretary-General of Kanchanaburi Rajabhat Cultural Center [or teacher’s college in those days].

On 20 Nov 1990

The Archeology Division began digging two trenches beyond the site of the foundation’s excavation to the south, but no bodies have been found. By 23 Nov a third trench was dug near the site previously excavated by the villagers.

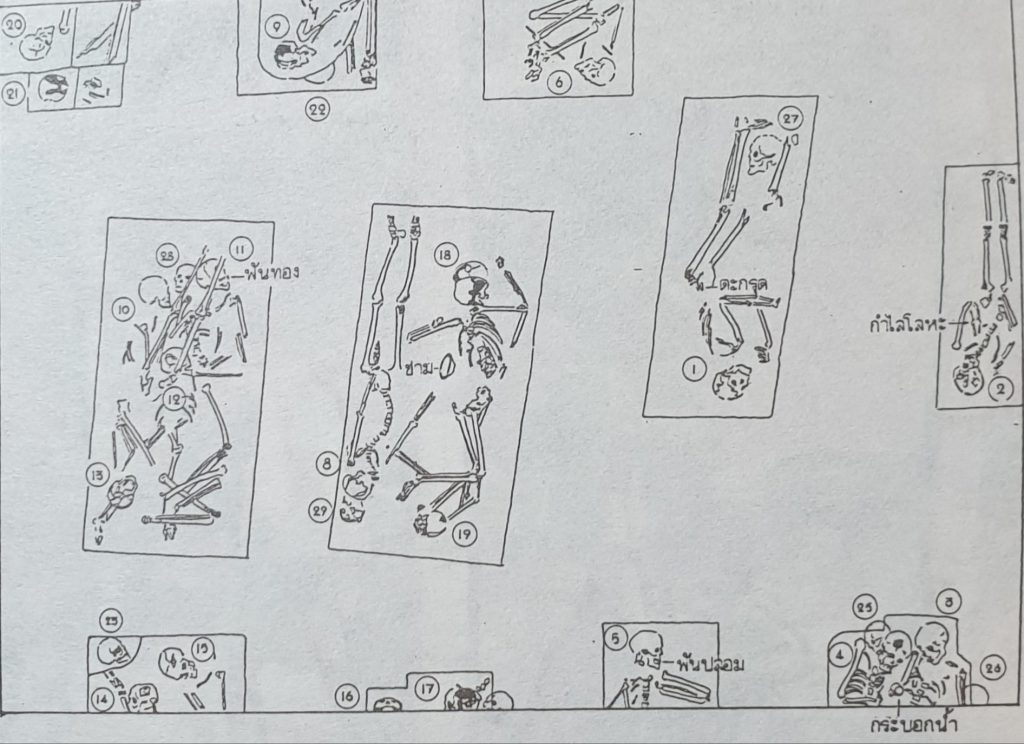

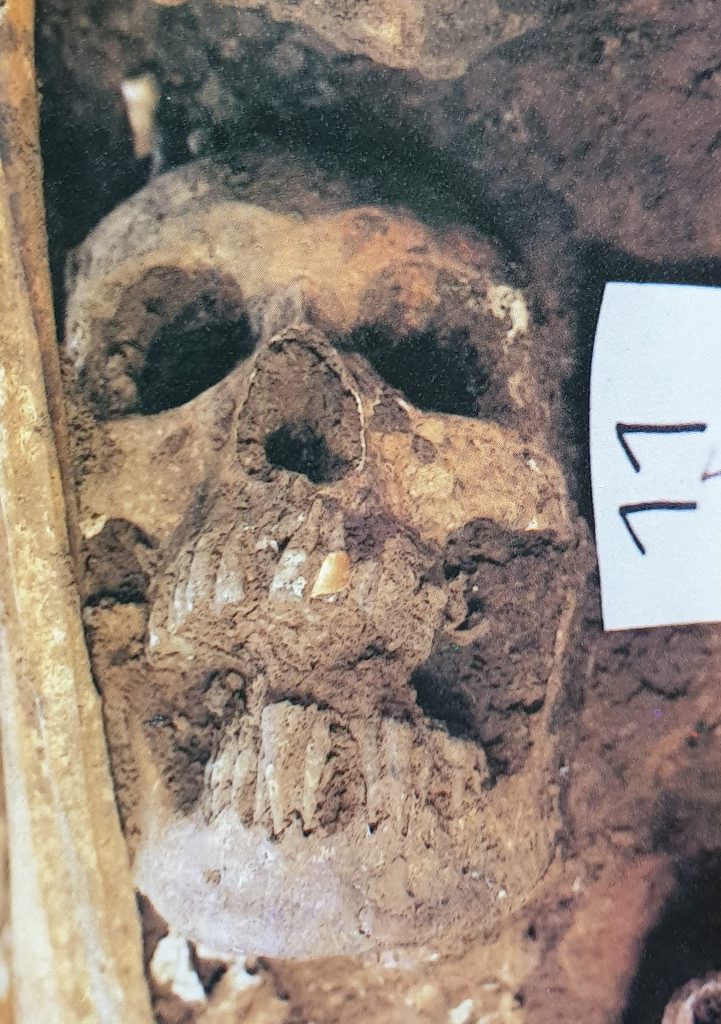

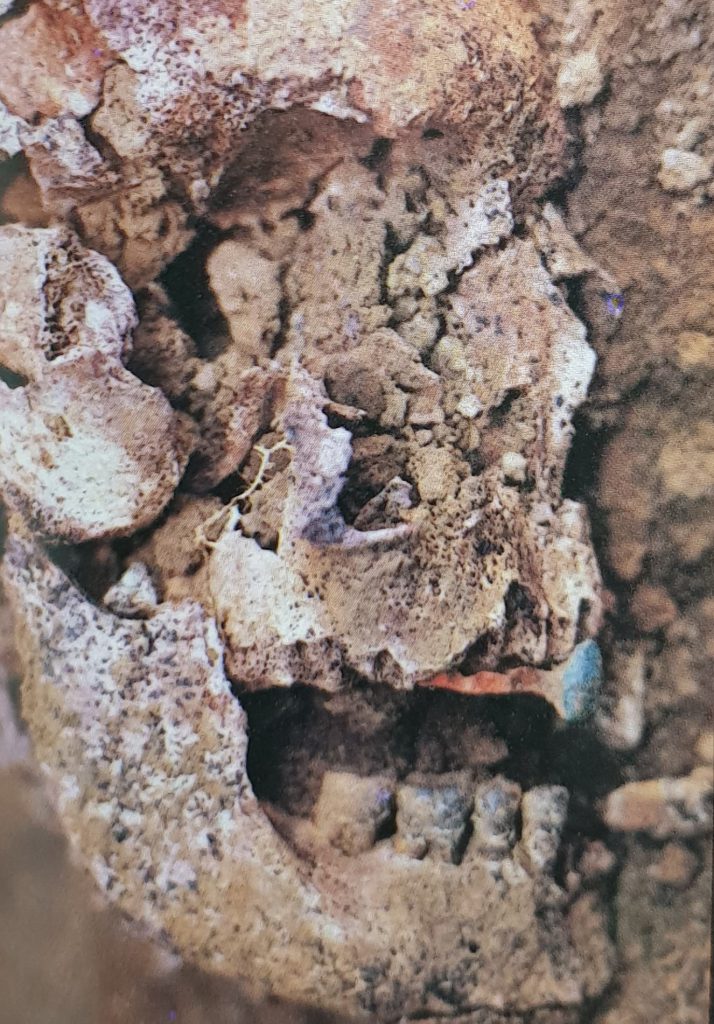

In this third area, about 4x5meters in size, 35 over-lapping skeletons were found; 24 facing north, 11 facing south. The skeletons were deteriorated due to the fact that it was under a sugar cane field and had trapped groundwater. Most of the skeletons were located 60-70 cm below the surface of the soil. One of those skeletons belonged to a girl under the age of 10, as she still had her baby teeth. And at the same time, a bracelet was on the left arm of this skeleton.

From the excavations of archaeologists many double burials were unearthed. There were two burials in the same pit. That is to say, after the first burial, the soil was layer about 30 cm. and then the other corpse was placed on top and then the grave was covered.

In addition, they also unearthed the belongings of the deceased like metal water cylinders. Some had a stamp written on the origin of the production as Hong Kong or Japan. Some reports say the year of manufacture is 1939. Two pieces of metal Takrud [a tube-shaped amulet or talisman] were found and a piece of rope was found in the Takrud’s string loop. The Takrud was found at the hip of the skeleton. (That person had tied the takrut around their waist)

Some of the bodies were found with teeth inlaid with gold. Some of the bodies were found wearing dentures. Seven bodies were found to have black teeth caused by chewing betel nuts.

The archaeological evidence is consistent with the stories of the elderly that in the past this area was an Asian labor camp and witnesses had seen the digging of the graves of Asian laborers (reported to have been Tamil-Indians). It is suspected that there may still be more remains in the areas adjacent to the sugar cane field, but they had no permission to work there.

The statement is as follows:

Mrs. Urai Bosub

65 years old, Pak Phraek villagers, interviewed on November 21, 2000

“Said that at that time [1942], he was 15 years old, the Japanese came to Kanchanaburi. An Asian labor camp was built along the railway line from Ban Khao Din to Ban Bo. (Presently Phahon Hospital). Asian workers had a hard life, waking up early and going to work hard with not enough food. Malaria, dysentery and cholera caused many deaths. Some children have no rice to eat, no milk to eat, and were so skinny. The deceased laborer were be buried. The bodies were tossed and piled on top of each other and sprinkled with lime to reduce bad smell because the grave would not be covered at once as so many corpses had to be disposed of. When enough corpses were added, the grave was filled.

Mr. Iam Bosub, 81 years old, interviewed on March 20, 2008.

The Japanese camp was located at Ban Bo School. As for the Indian, Javanese, Malay labor camp, at Ban Bo Hospital. Mr Iam saw that many workers fell ill. Some people are cholera. Some people have wounds all over their bodies. There were many deaths. and the bodies were buried behind the school [now the Phahon Hospital sit].

The abbot of a temple in Ban Pong [near the beginning of the TBR; 50 Kms from KAN] had seen Asian Indian laborers get off the train at Wat Don Toom and walk to Kanchanaburi. The procession was accompanied by children and women. Most of the women were the wives of male workers who left for work. Women are also housewives and cooks.

Robert Hardie, a British physician POW, said of the Asian laborers: A large number of Chinese, Malay, Indian and Tamil laborers were persuaded to build the Death Railway. By the way, Japan claims that it’s a light job and good pay. They were sent to Thailand by arriving at Ban PongThe [Wat Don Toom] from there they were herded on foot to Kanchanaburi and beyond. Asian laborers numbered in the tens of thousands and camps were set up along the railroad tracks.

We have heard of the horrors of death from the epidemic among the Asian laborers. Many were so ill that they could barely speak. Some Asian laborers died in the forest, rotting corpses were not buried. The sanitation system does not have crowded people. There were swarms of flies all over the place. Importantly, there is no medical treatment in these camps.

Muthammal Palanisamy, a former teacher in Malaysia has tried to piece together the story of the surviving Asian laborers returning to Malaysia after the war. She has gathered information from 12 Malaysian laborers and that story is being compiled and will continue to be written in a book. It is noteworthy that many Indian-Malay Asian workers say the same thing: the Japanese soldiers invited them to work on building a railway. The construction of this railway will help Japan send troops to fight against the British and this railway would help to liberate India. This is one reason why the Tamil-Indians who were sent by the British to work in Malay decided to join the construction of this railway.

When studies revealed that these were not corpses associated with prehistoric civilizations, Arts Department itself did not continue the survey and let the Bodhib-havana-songkha Foundation come to exhume the rest of the body from the area.

===============================

The next question is, where are those bodies now?

The information obtained is as follows:

In the Foundation’s documents, it stated that after excavating for 10 days, they had enough skeletons to fill a six-wheeled [medium sized] truck. The bodies were brought back to the foundation’s HQ in Bangkok to make merit and perform funeral rites. After cremation, the ashes were taken to a cemetery in Saraburi Province [northeast of Bangkok]. Annually. Chinese rituals are performed during Qingming [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qingming_Festival]

Before cremation, the Thai Department of Fine Arts inspected the skeletons at the Bodhibhavana Welfare Foundation in Bangkok. But little additional information was gleaned because of the skeletons were all jumbled together with others from other cemeteries.

This was the largest group of remains that were excavated and disposed of.

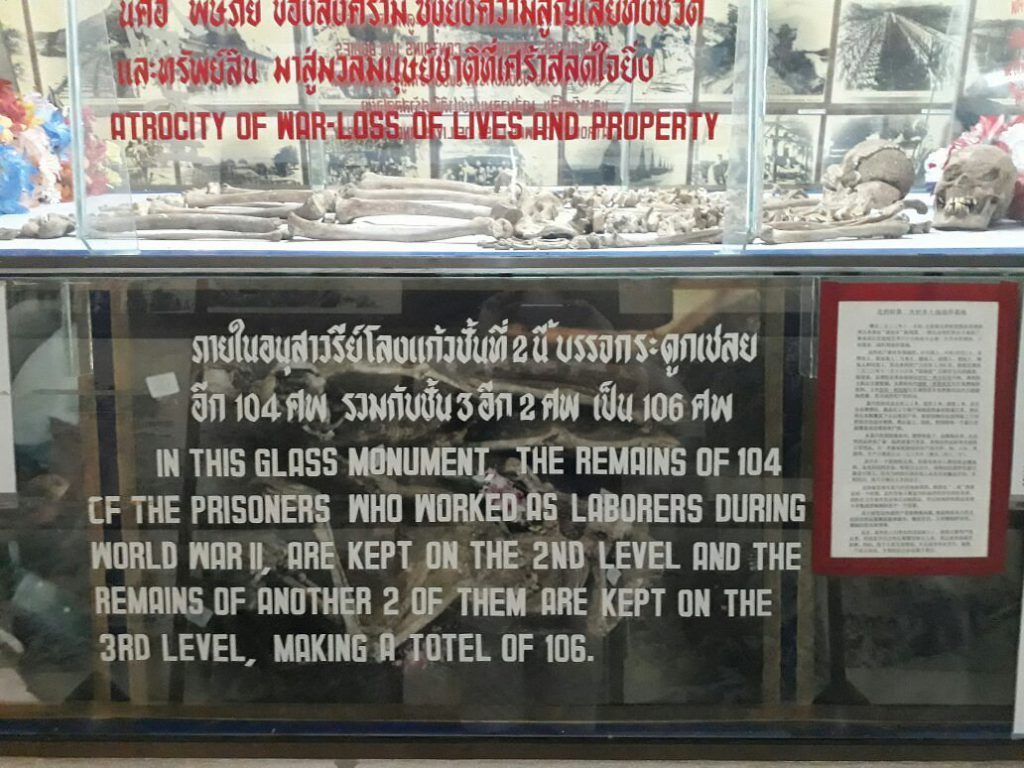

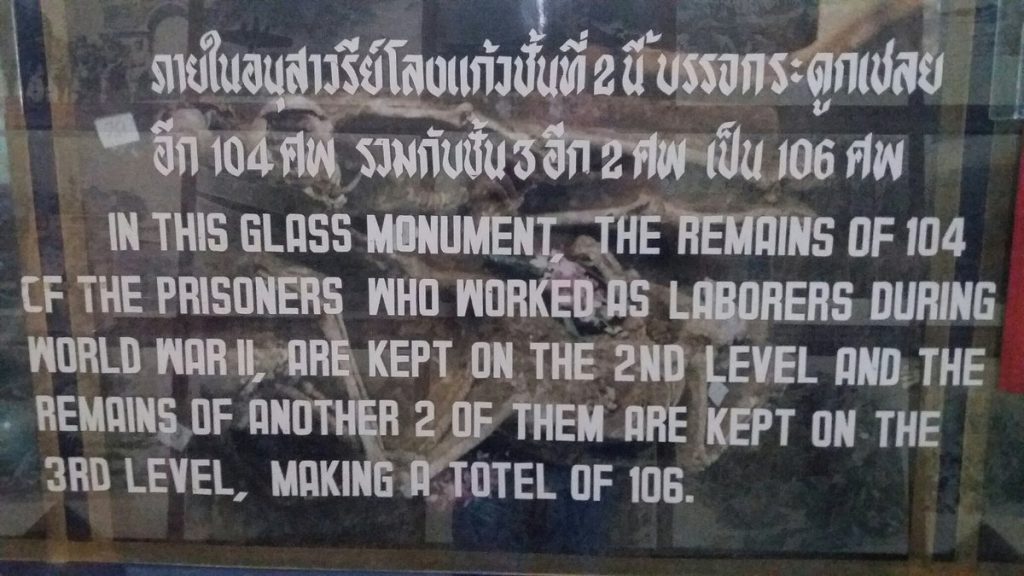

The second group of 106 was handed over to the Axis and Prisoners of War Museum beside the River Kwai Bridge. There two of these Asian laborer skeletons remain on display in a glass case. The other 104 skeletons are located in another portion of the museum.

The last 33 skeletons, as written in International Herald Tribune, New York Times by Thomas Fuller, March 11, 2008:

Thomas Fuller came to Thailand to cover news about the Asian laborers who helped build the Death Railway and interviewed Ajarn Worawut Suwanarit about the Death Railway and the funeral of Asian Workers. Including interviews with people who were involved in events during World War 2 such as Mrs. Urai Bo Sap and Nai Thongyu Chalwankumphi a former Malaysian Asian laborer who lived in Thailand. (Currently deceased)

In one news article:

After many skeletons of Asian workers were excavated at Pak Phraek, Kanchanaburi, Ajarn Worawut Suwanrit requested the province to establish a memorial museum or cemetery for these workers. But did not receive any response from government agencies.

The news also states that Ajarn Worawut Suwanrit exhumed the bodies of Asian workers with his own funds and deposited 33 skeletons at the Muang Sing Historical Park for preservation.

In 2008, Ajarn Worawut Suwanrit and Thomas traveled to Muang Sing Historical Park to ask to see the skeletons that had been deposited, but received the news that those skeletons had been buried a few years earlier. The reason the skeleton was buried was due to the musty smell of the skeleton storage room and complaints from staff and visitors. So one of the staff dug a hole for 33 skeletons.

I called to the Muang Sing Historical Park, the woman who answered the call and I asked about the person named in the news to confirm that those graves were actually dug. But those who buried them were temporary workers and left soon thereafter. And now no one knows where the 33 skeletons of Asian laborers were buried, because the officers in those days were all retired, and some of them had died. But when looking back at news content in the New York Times in 2008, it added that the pit where those skeletons were buried was near the compost heap, he used the term compost heap, which no one would know today because it was many years ago. That means Thomas Fuller and Ajarn Worawut knew where the 33 bodies were buried (but Ajarn.Worawut has since passed away.)

=======================

I am not here to attack the work of any agency or person. Just take the story that came from it including the published stories, because I believe that more and more people would like to know where the skeletons that were unearthed reside today.

As per the information in many books and documents Including information from interviews with various people of Ajarn Worawut, it is believed that in the area around the City Hall, Phahon Hospital, as well as the area around Soi SaengChuto 14 and surrounding areas, there are likely to be many remains because the former was an Asian labor camp. At the present time, no one wants to dig or do anything more to learn what stories could be told.

The information on the existence of the Asian labor camp in Thailand is exactly the same as what I received from a foreign friend who said that the area of City Hall and Phahon Hospital used to be an Asian Indian labor camp (Tamil people) because there is evidence of aerial photographs during World War II.

Personally, I believe that in that area there are probably skeletons of Asian laborers left. Without causing a panic for people in the area some just want to know the history of the area there. Many, perhaps most, wish to leave the story untold. Perhaps out of fear that it might devalue their land. Some areas are tombs of Asian laborers who are still after all this time.

As I seriously explore other regions of the railway, I talk to many villagers. I have learned the story that in the past that there used to be many small camps along the Death Railway. Many skeletons have been excavated. For example, around Kui Yae or around Tham Phi Station (before reaching Khao Khad Chong) have been excavated, but this is not news. Because that area a long time ago was a remote area. Uninterested, the corpses were carried to the temple and burned to make merit. The tombs of the Asian laborers cannot compare with the tombs of the Allied POWs. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWCG) Cemetery looks shady and beautiful. On the grave markers of the Allied soldiers are words of lo, pride and remembrance. But the unmarked graves s of the Asian laborers are often in the middle of the forest; in the villagers’ gardens. Some are in public areas or government offices. There is a monument at Wat Yuan [next to the CWGC Cemetery; about 2KMs west of the Hospital site] that is reported to contain over 10,000 sets of remains that were unearthed post-war as road construction and building proceeded.

The corpses had to lie in the cold ground, undiscovered and invisible. No one knows their existence. As I said above, first I dedicate this writing to the Asian laborers. So that they still exist in the perception of people today. I believe that not many people have heard of these stories. Second, I would like to dedicate this research to Ajarn Worawut Suwanrit who was a teacher I loved and respected very much, Ajarn WorawutSuwanrit, would have liked to create a museum or cemetery dedicated to these Asian laborers but was unable to push it to happen.

I would like to use this article to help signal to those involved that we should not forget these Asian laborers.

Much on the railway that Thai people use to travel from Nong Pla Duk to the Nam Tok station; that Thai people have used directly and indirectly to earn a living from tourists, was built by these Asian laborer; with the sweat, the physical force, the life and the tears of the Asian laborers.

But what we usually hear is that Allied POWs built this railway. I do not agree with the expropriation of the land of the people who live and turn it into a cemetery. But I would like to suggest that soil from the areas that used to be camps or cemeteries of Asian laborers should be collected and used to make a statue or incorporated into a memorial for them. Or will we be haunted by a mourning message from them – as was Khun Sompong. That soil is the flesh, the hair and the bones of the dead Asian laborers decomposed over time.

I said as if I could do it myself. But I can’t do it myself. I have to ask everyone to help communicate these stories and pictures of Asian laborers to follow this link https://www.facebook.com/110480247217381/posts/313541240244613/?sfnsn=mo

If anyone is interested in joining the Death Railway Explorers group, follow the link https://www.facebook.com/groups/2342060092765924/?ref=share