There are any number of fragmentary and not well documented (and at times quite disturbing) anecdotes about the romusha and the overall TBR saga. These bear reporting if only to log them for future investigation. Many of them are provided by Prof. Boggett in his essay series (see Section 20.7).

The worst is a story that he apparently extracted from post-war trial transcripts[1] in which a Malay romusha accuses the IJA of cannibalism[2] when rations ran short in the highlands camps circa APR 1943. His account is quite vivid – almost to the point of being believable.

Perhaps only slightly less disturbing are tales of sexual predation. The first occurred during the ‘recruitment’ of romusha workers in Southern Malaya. Boggett[3] tells the tale that Tamils he terms kirani – apparently fellow Tamils that were mid-level overseers of the plantation coolies (I believe the word is actually kerini = the Tamil word for ‘clerk’ )– were enlisted by the occupying IJA to ‘assist’ in recruitment of their subordinates. Their cooperation was reportedly induced by a promise of immunity from such deportation for themselves and their families. Boggett recounts how one of the groups targeted were young married men. Their now abandoned wives (young and pretty) were them coerced into becoming mistresses of the recruiters in return for food and shelter.

More than a few Tamils accepted the ‘contracts’ from the IJA and boarded the north-bound trains with their meager belongings and families. Boggett[4] suggests that at some of the more isolated camps the women were not infrequently sexually abused by the IJA camp guards. Fragmentary reports say that some of those romusha (to include some Burmese-Mon women) found their way into comfort stations (IJA brothels aka iangio). One of these was located where the popular HinDat hot springs pools are today. It is generally accepted that the majority of the comfort women were Koreans. US POWs report that the first train they saw on the TBR was carrying a group of such women.

While there are only a few reports of such exploitation farther north, the ‘recruitment’ of Burmese workers took a similar twist. While the IJA fought in central and western Burma, parts of the eastern sectors that bordered Thailand were administered by collaborating Burmese officials — again similar to the Vichy French arrangement in Europe. When they received requests to ‘recruit’ workers for the TBR, the first on their lists of ‘recruits’ to be rounded up were their political (and personal?) enemies.[7] It is said that so many young men were shipped south to the TBR that rice production fell to nearly starvation levels. Here the figure of 85K Burmese / Mon recruits is mentioned — see below.

Another undocumented anecdote concerns a post-war encounter between an Australian graves searcher and an IJA Corporal who claimed to have been an administrative clerk. He provided what seems to be the single first-hand (if not well documented) report of romusha numbers. The Corporal[5] related figures of 250K Malayans and 100K Javanese who worked the TBR. Of those, at least 170K were said to have died there. Since this clerk was at a highlands camp in Thailand, it is doubtful that he would have access to figures or nationalities working either in Burma or on the Kra Isthmus railway. So such figures, if accurate in themselves, are bare minimums.

One aspect of the IJA record keeping tends to confuse any figures for the romusha. At times, the IJA counted and sorted people by nationality; at other times by ethnicity. By the former, a Malayan could be a Tamil, a native or even Chinese from Malaya. By the latter, Chinese could mean a Singaporean , a Malayan or possibly a Thai. So it is difficult to add figures from different places and times to arrive at accurate figures. The Allied POWs were seeming sorted only by nationality.

In another essay, Prof Boggett claims that Indian soldiers serving with the British Army in Malaya were separated from their white European colleagues and that some ended up on the TBR with Tamils from Malaya.[2] Ethnic sorting? In addition to the scant information that Vietnamese worked the TBR, Boggett also relates an anecdote that Laotians were imported as well. [7] It stems from reports of a cluster of Lao-speakers near Three Pagodas Pass more than a generation post-war. In that same essay, he quotes a Burmese author who suggests that the number of Burmese / Mon workers on the TBR was closer to 120,000 as opposed to the generally accepted figure of 85,000 — once again no actual documentation exists.

In his North Texas Univ Oral History interview (OH -192), TXNG PVT Ray Ogle relates a romusha-related incident. He was with the Fitzsimmons Grp that eventually crossed the border into Thailand. There they became aware that cholera was raging some of the nearby camps. In mid-1944, he was returned to the SongKurai area a part of a work party loading and unloading trains as they passed to and from Burma. While out gathering fire wood he picked up a fallen branch and was shocked to see that impaled on it was a human skull. It could only have been from an unburied romusha.

To date (2022), I am unaware of any official attempts by any agency — military, humanitarian or otherwise — to locate any of the thousands of remains that must still remain in the more western areas of Kanchanaburi. Indeed, the dam on the Kwae Noi river flooded much of that area from about Km 225-280 centered on Konkoita. But that leaves the next 20 kilometers up to the Thai-Burma border still accessible. Unlike the two excavation sites in the city of Kancha-naburi, there are no documented reports of finding of skeletal remains by farmers or construction crews. Personally, I could understand why a farmer making such a discovery would not be tempted to report it to local authorities. Surely, the aftermath could be quite detrimental to his farming endeavors! It is also understandable that there have been no organized efforts to make such a search. As is pointed out in the Social Sciences portion (see Section 29.2) of this site, there is little interest on the part of any of the governments involved in re-awakening this horrendous chapter of history.

===================

In his book, To the River Kwai, John Stewart relates a story (pg 88) that seems to stand unique. Even he claims that it might be apocryphal. But it bears repeating as a stand-alone anecdote: It seems that in 1945 during one of the bombing raids on a bridge near SangKlaBuri, about a 100 British POWs were herded on to that bridge as ‘hostages’ in the hopes that the presence of people on the bridge — even if the pilots could not identify them as POWs — would be a deterrent for attacking that bridge on that day.

The POWs, too, introduced uncertainty into the historical record by their lack of understanding of the geography and place names. At times they simply mis-heard the Thai names and twisted them into their own usage. My favorite is the place they called Tamwin; which turns out to be Tha Muang. Many of the camps along the TBR are referred to in multiple ways. Sometimes the Americans, British and Dutch all called the same location by a different names. Upon their arrival on the trains they all seemed to know that they were in BanPong. But they failed to appreciate that after a 2-3 Km trek they had arrived at one of the NongPlaDuk camps. Other place names are a mix of Japanese and Thai; Kin Sai Yok for example where the ‘Kin’ was added by the IJA.

The Allied POWs were subjected to multiple types of humiliation and de-personalization. LtCol Dunlop recounts one such practice that occurred prior to shifts among the camps in the Hintok area. The men would be handed a piece of cellophane paper and the next morning they would need to arrive at the daily muster with a sample of their feces. This was an effort to identify those with dysentery, particularly amoebic dysentery which would disqualify them to move from that camp to another.

In another undocumented statement, Prof Boggett makes the claim that the Thai-anusorn Shrine “mentions the deaths of Japanese military personnel”[6]. I can find no such reference. The translated inscriptions clearly mention both romusha and POW deaths, but not a word about IJA soldiers. [see Section 14.3 for the full Thai-anusorn story]

One of the more bizarre stories that persists to the present day is also touched on by Prof Boggett[7]: that of the Ban Lichia cave treasure. Perhaps not quite as well known as the Philippine’s Yamashita’s treasure, the thought of spoils stolen from Burma and buried near Thong PhaPum still brings the occasional fortune seekers to that area. Boggett claims that he was able to trace the rumors of sure a buried treasure to IJA soldiers who settled in that area post-war, rather than return to Japan. [see Section 21.0 for similar stories] This controversy was reignited when a Thai Army General was found to have an extraordinary amount of (unexplained) wealth that he bequeathed to heirs in his will. He had been known to be a ‘believer’ in this treasure! Had he found it?

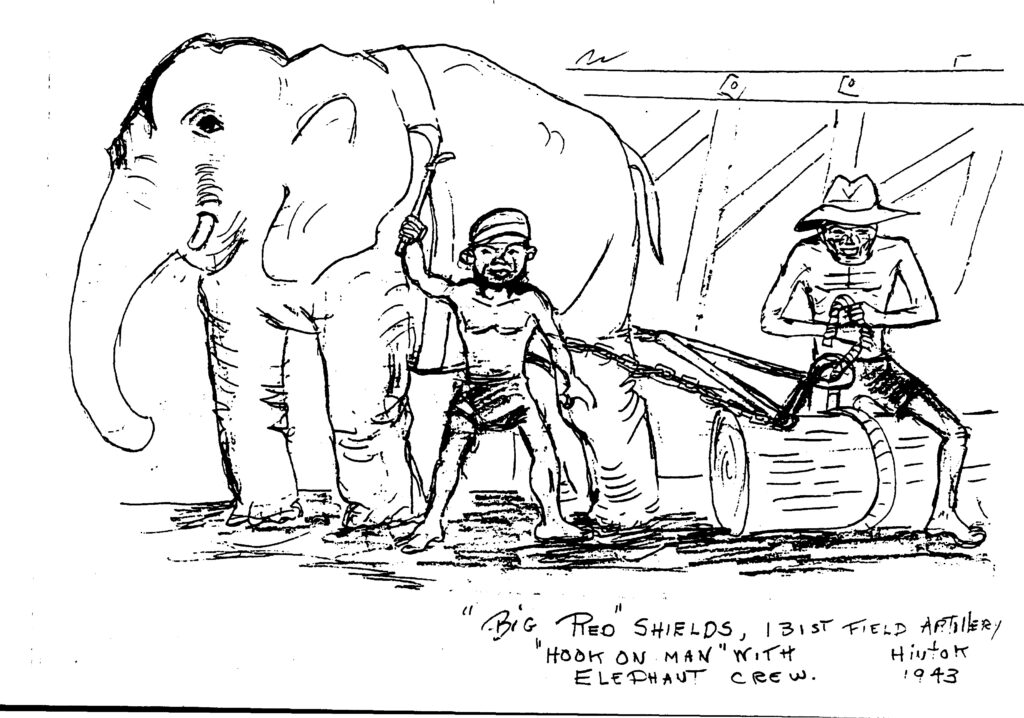

Another group who were victims of the war in Burma were the ‘working elephants’. Again we thank Prof Boggett for a story by a Burmese mahout [7], who says that pre-war there were as many as 10,000 elephants then by 1945 there were only 2,000. There seems to be three reasons for this: 1) some were killed for their ivory; 2) some were used on the TBR; 3) many were ‘drafted’ as pack animals as the IJA withdrew into Thailand. A lieutenant in the IJA relates how the elephants received equal pay (1 rupee per day) as their human counterparts working the TBR.

It is of note that no US POW was seriously injured or executed (murdered) by a guard. But one POW admits to murder. For the sake of his family I will not identify him nor the exact location. He related the circumstances during an Oral History interview. He and an Australian POW were involved with a Japanese guard in some black market-style trading. The guard had freedom of movement. He would take money or items to trade and return with items the POWs needed. On that fateful day, he returned with an unusually large haul. He let it be known that he was supposed to be on liberty and not at the camp. The two POWs produced a knife and killed him dumping his body in one of the open latrines. Reportedly no one ever found that body and the 2 POWs walked away with his money and goods. [To me this story seems a bit up-side-down as to whose ‘goods’ the POWs actually stole, but I can only relate the incident as it was told by the perpetrator. It also sees incredible that he would include such a confess in a public interview. Bizarre!]

Per the MANSELL website the only British prisoners working on the Burma end of the railway were known as the British Sumatra Battalion: 498 British 2 Australians from Sumatra under Capt Authored, including Australian surgeon Colonel Coates worked at the 18-kilo camp then joined up with the Americans under Capt Fitzsimmons.[8] [see Section 8.22]

There is also a report by one of the USN personnel (again I will not ID him) stating that he had quite a disdain for LTC Tharp. In his mind, Tharp was too accommodating to the IJA guards and camp commandant. This POW stops short of calling him a collaborator, but describes how other officers — both Army and Navy — did a much stronger job of standing up for the enlisted men. He goes on to describe how Tharp managed to hide a .22 caliber single-shot pistol throughout his POW time. This POW claims that the Japanese knew of this weapon but never took it from him. [It makes one wonder if this POW was not somehow a bit disturbed and/or delusional.]

Another US POW relates a story of torture and revenge that he says happened near the Phetburi camp. It started when a group of Thai men attacked the guard of one of the POW work groups. They beat him badly enough that he died soon after the POWs carried him back to camp. When they related their story that placed the blame on locals and not themselves, the Camp CDR contacted the Kempetai to investigate. They rounded up a dozen or so local villagers and proceeded to ‘water board’ them, then force feed them water until their stomachs were bloated before beating them with bamboo rods. None of them would reveal who had killed the guard; even if they knew. The Kempetai even tried to intimidate a monk but didn’t actually torture him. After days of beatings, nothing was learned and as suddenly as they appeared the Kempetai released the locals and departed. Seemingly. the guard’s death was un-avenged. But a short time later, the Camp CDR and 2 soldiers drove into the town to shop. When they did not return as expected more soldiers went to look for them. They found the vehicle striped and the 2 soldiers beheaded. The CDR was never seen again. Seemingly, the Thais got their revenge, twice!

There is no way of knowing but the Phetburi area was a hot-bed of OSS / Seri Thai activity and they may have played a role in these attacks.

ESCAPE

Every soldier of every nation is taught that his duty should he ever be taken as a prisoner is to escape the clutches of his captors. Such was the thought processes of the Allied POWs who were captured in Singapore. A few were able to escape (evacuate) from the island before it was overrun. One group made it as far as Sumatra; just a short hop across the strait. But soon after Singapore fell, so did Sumatra. These mostly British escapees were rounded up and moved to the city of Medan. Within a few months (weeks really), they found themselves on the coast of Burma building an airfield near Tavoy (now Dawei). In June 42, they were moved north and were among the first POWs to work on the Thai-Burma Railway. They became known as either the Medan Group or the British Sumatra Battalion. They were the only British working in Burma.

But what about the POWs who found themselves on the TBR? The IJA cadre made it clear that the penalty for escape was death and they were serious. The Japanese were so sure that escape was impossible that the TBR camps themselves rarely had even an enclosure fence much less a barrier like barbed wire. We have any number of survivor accounts that speak to the attempts by fellow POWs to escape these camps.

But let’s examine the concepts involved. First one needs to know where you are in order to decide which direction to proceed towards friendly lines. Particularly for the seamen among the POWs, determining one’s general position would have been fairly easy. The men would obviously have known that they were in Thailand or Burma. The nearest Allied lines would have been in India or Ceylon (Sri Lanka) over 1000 Kms across the Andaman Sea. The China border was about 700 Kms due north; farther to any Allied bases there. So would one go west to the coast and hope to find some sort of transport or north through the mountains?

It turns out that these men had very little appreciation for just how mountainous this terrain was. One group who did try heading west estimating that they could reach the coast in no more than a few weeks, so that is how much food they tried to carry. As it turned out, they spent so much time going up and down that they made very little progress westward!

Other groups had similar experiences every trying to follow the contour lines north as opposed to crossing them. None got particularly far before either dying in the jungle or being recaptured. The IJA had made it known to the locals that assisting any escapees was punishable by death for them and their families. There was also a bounty offered for delivering the escapees back to IJA control. The local police were happy to assist in this effort. IOW, none of the odds were in favor of the escapees. In fact, there is no recorded account of a successful escape from the TBR—except at the very end of the war.

Of course, a major plot point in the famous movie is the escape (and return) of the US POW played by William Holden[1]. Never happened! Just as the rescue of the survivors of the Rakuyo Maru revealed to the world the fate of the POWs in Burma and Thailand, any successful escape would have been well publicized; after if not during the war.

Oddly enough, one of the leaders of an escape attempt was an American citizen who was actually serving in the British Army and was on LtCol. Toosey’s staff during the bridge building. He led a group of 7 who thought that they could indeed reach China by going north. After a few weeks, CPT Pomeroy and two others were herded back to ThaMaKam in chains. The others had died in the jungle. These three were promptly executed and their bodies buried away from the camp. It was said that the executioners usually made the victims dig his own grave. This story ends with his brother coming to Thailand soon after the war and with the help of some Thais located, unearthed and carried his brother’s remains back to the USA.

So was the fate of just about every escapee. Some men had escaped the compound at Singapore soon after their capture. To ensure that the others knew what was in store, they were execute in front of the assembled POWs. I’d imagine that there was a lot more talk and planning for possible escapes than there were actual attempts. The availability of food was low enough that storing away any for future use would have been nigh on impossible.

We do know that in the latter weeks of the war (of course that fact was not part of their planning), 2 US POWs successfully walked away from the work group building an airfield at Petchburi. By the summer of 1945, the Seri Thai and Allied operators were becoming bolder in their operations. Security by the IJA guards was also very lax. They were also near a large Thai community. While working unguarded, 2 members of the USS HOUSTON crew, Ammo specialist Harris and Coxswain Hoffman were approached by some Thai men who were carrying a note in English from OSS agents operating in the area. Naturally, the two were suspicious of an entrapment so it took a few meetings to gain confidence that there was a possible route of escape. So finally, they left with their Thai guides. They were escorted inland towards Burma where they finally met the OSS agents hiding in the mountains. They were able to provide information about their fellow POWs in Petchburi and back in Kanchanaburi. They spent the next few weeks assisting the agents in surveilling the camp. But the war ended before arrangements could be made to evacuate them. They eventually returned to the camp and were evacuated with their countrymen. By quickly linking up with the agents, they were able to avoid all of the pitfalls that befell all the others.

It should also be mentioned that however many dozens of POWs died during the attempt or were executed for escaping, just about all would have been counted as MIA (Missing in Action) since their remains would not have been recoverable.

======================

Finally, there is one additional anecdote that pertains to the US Field Artillery unit on Java. One survivor describes how, as the 2/131 moved west to prepare for the defense of Java, they dragged with them excess cannons (probably belonging the the evacuated 26th Bde) and left them disabled and unmanned all over the island. Later, the IJA questioned the members of E Battery about the ‘other soldiers’ who manned those guns.

[1] AUS War Memorial collection document 54/1010/9/94 and ANA Collection document A476/1-80794

[2] Boggett essay Part 24 text and footnotes

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Boggett essay part 28 page 81

[7] Boggett essay 22

[8] http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/death_rr/movements_1.html ; Clifford Kinvig relates this same connection in his book.

There is an interesting side-story to the fall of Singapore. In addition to over 130,000 British and Australian POWs there were about 45,000 Indians who were part of the British Army. They do not appear as part of the TBR saga. Their interaction with the IJA took a completely different path:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_National_Army_in_Singapore

A multi-part (9 I think) interview series with a British TBR survivor; it sounds as if he was a member of D Force of mainly AUS POWs.

Naturally, the Japanese forbade the keeping of records, diaries or photographs. Some men risked their lives to keep such records. One even had camera whose film he managed to keep and develop post-war. The few that have come to light are battered and marred but capture moments of POW life.

Most of the records we have were drawings secreted away by the men. POWs Ronald Searle and Jack Chalker were the most prolific artists who have published those drawings. For copyright reasons they cannot be posted here. I do suggest that anyone interested do a simple GOOGLE search to see examples of theirs and the works of a few others.

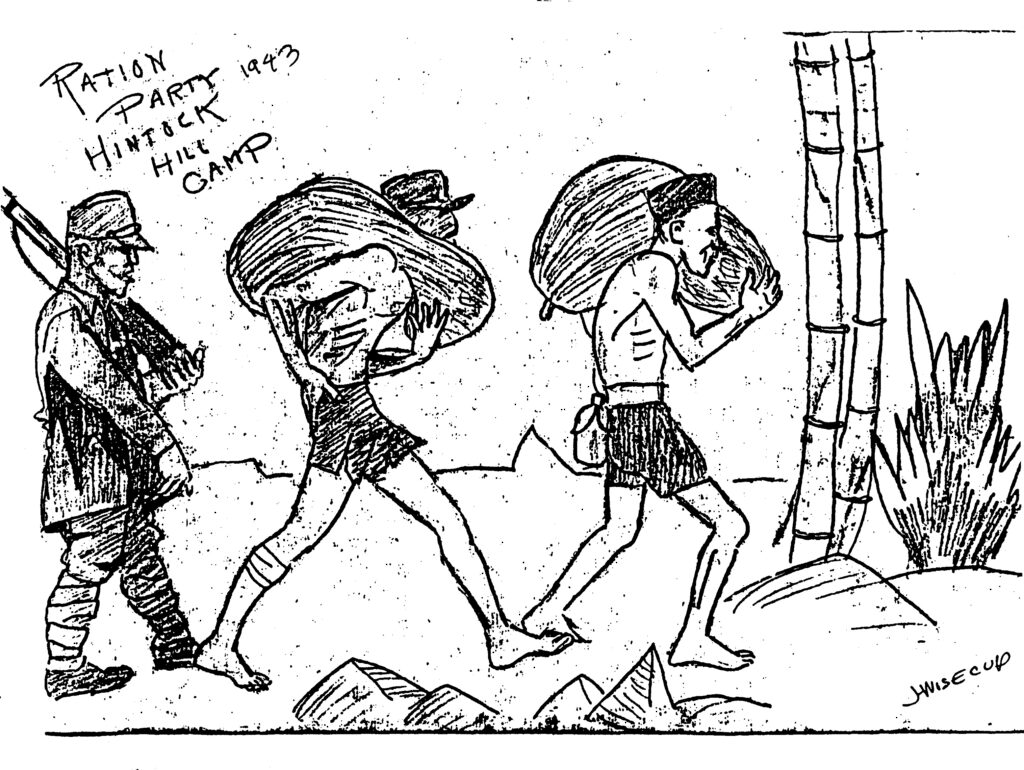

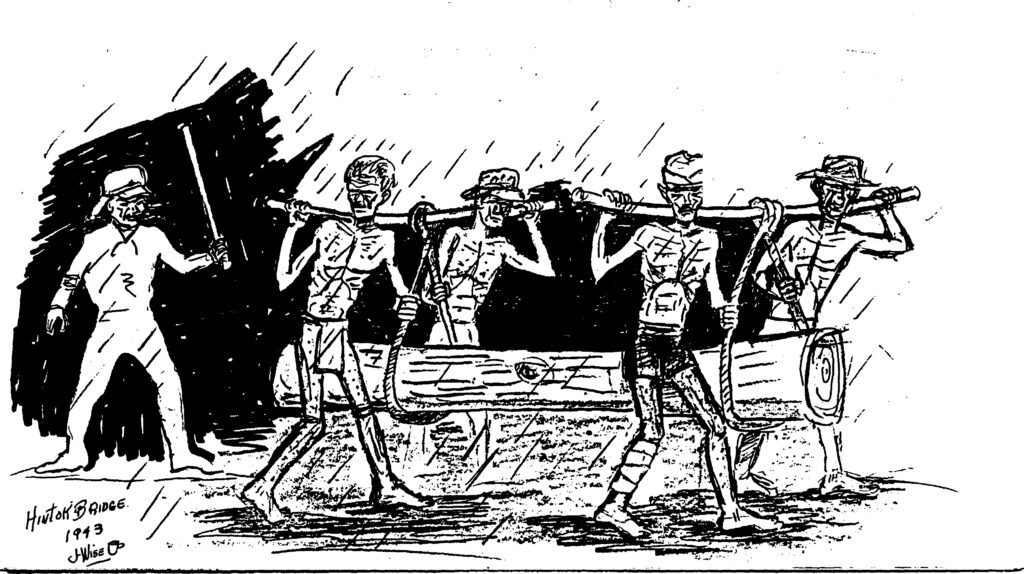

US POWs John Wisecup, Roy Offerle and Frank Fujita also made numerous sketches during their POW time. I received permission from the copyright holders ay the Univ of North Texas to post some of John Wisecup’s.

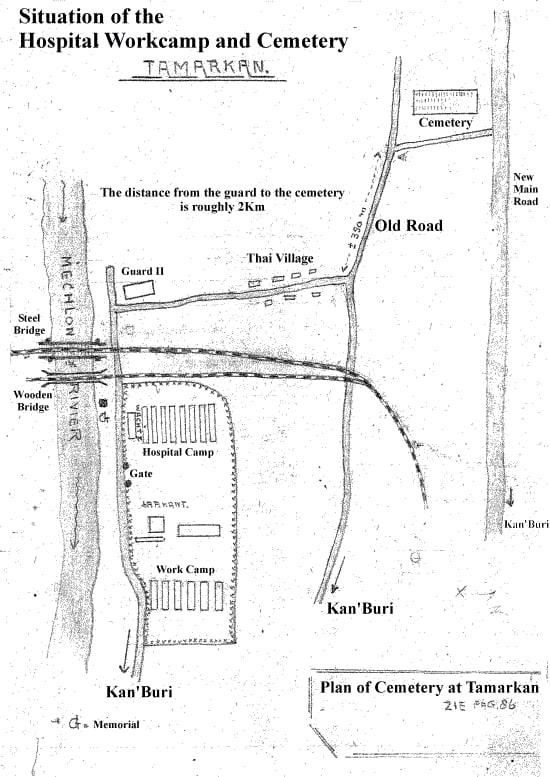

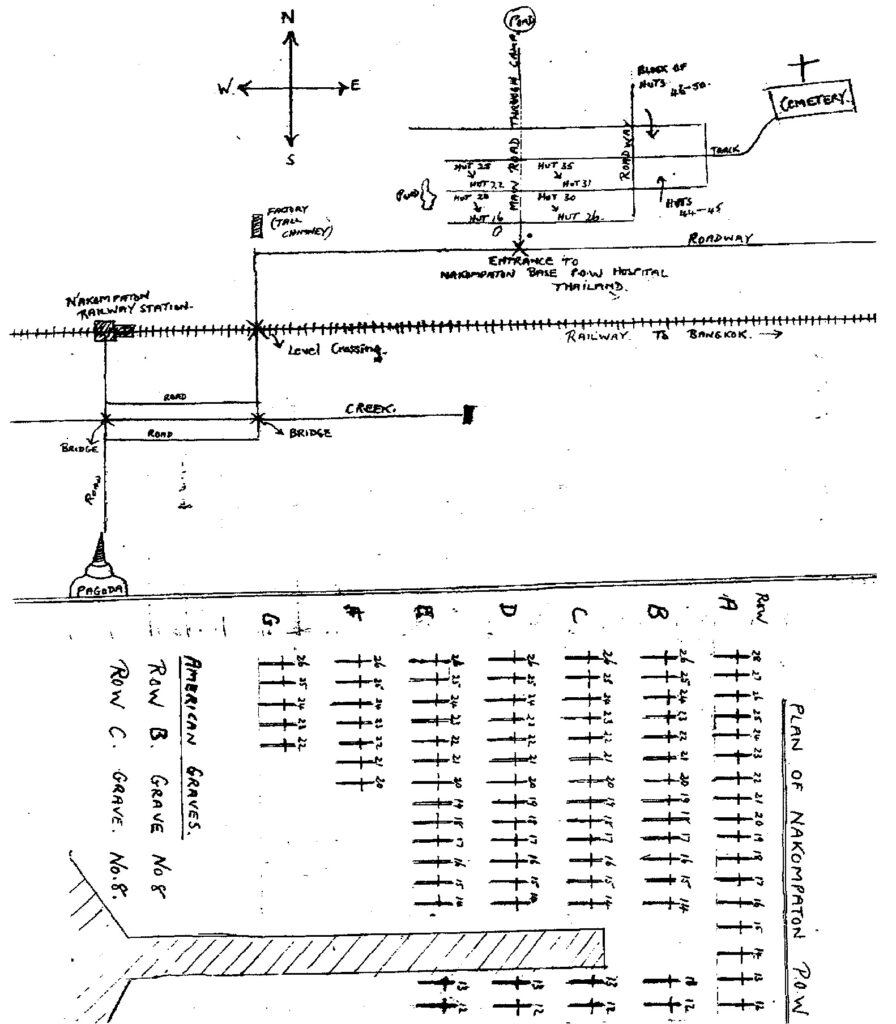

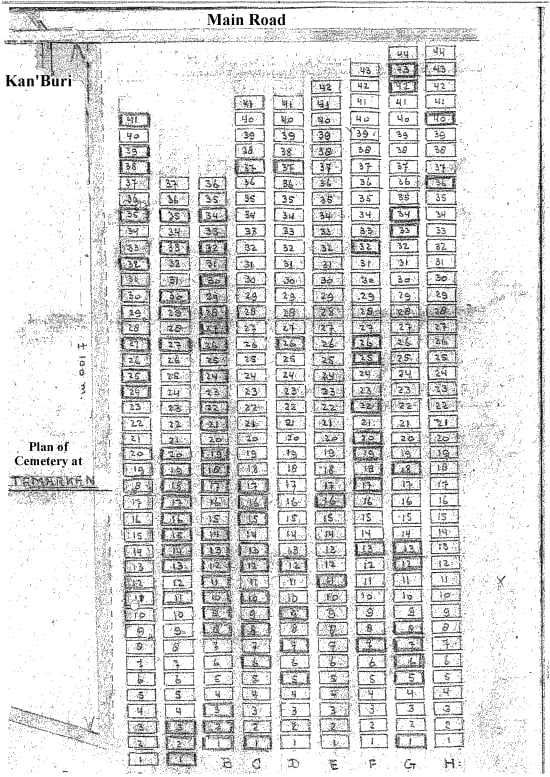

In addition, immediately post-war, many POWs made drawings and maps of the numerous work and grave sites of their comrades.

================

We know for certain that PVT Edward “Dusty” RHODES was killed on 5 Mar 1942 [1], prior to being taken as a POW. His was the third and last pre-POW death among the TXNG. But what were the circumstances of his death? We are still not sure. LTC Tharp himself notes the date and place (Bandoeng) and lists the cause as accidental GSW. But how?

From oral history interviews by the Univ of North Texas, we get two rather disparate accounts offered by fellow soldiers both of whom should have been present as witnesses, yet their accounts do not seem to agree. The interviewer — in both cases was the same man — but he did not challenge the second version as being incompatible with the first. So no clarification was forthcoming.

One man states that RHODES was on guard duty and during the change of guard and the exchange of weapons or ammo, he was killed when the weapon was inadvertently discharged. There is nothing implausible abut such an event. Other accounts relate that during the stopover in Hawaii, they had picked up WW1-vintage Springfield rifles. These were issued after their arrival on Java but the men had little to no training in using them. This unfamiliarity could easily have resulted in an accidental discharge.

Once again, I re-iterate how I see this saga unfolding as if assembling a jig-saw puzzle. Each piece, large or small, links together with others to provide a clearer picture. Not so with these two accounts of what should be the same event. The second account differs so much so as to suggest that one of the men is not actually describing RHODES’ death. That account involves a booby-trap gone wrong.

We know that after their brief combat in support of the Australians, the 2/131 withdrew and was awaiting new orders. Other accounts tell us how after the surrender but prior to actually being taken as POWs, the soldiers destroyed their artillery and some of their other equipment. We are told that they were collecting the rifles into the back of one truck. Someone got the idea to leave bullets in a few of these as a booby-trap for the Japanese. The second description says RHODES died when one of those weapons discharged. If indeed his death occurred on 5 March, then the capitulation of the DEI had not yet occurred. It was still three days away.

In and of themselves, either account is plausible if not exactly probable. But these accounts are so disparate that there seems to be no way to interlock them as puzzle pieces. IMHO, the problem with the second account is its timing. The bobby-trap would have been set after the capitulation, when the men knew that they were soon to be POWs. They did not know this on 5 March. While awaiting new orders, guarding the perimeter would have been a necessity. I propose that the guard duty account is the more likely one to be accurate. Perhaps there was an accidental discharge of a weapon in the following days but it was seemingly not the event that killed PVT RHODES.

Linking unrelated accounts of events can in some cases be very enlightening. But there can also be an element of confusion when the accounts do not quite agree. Such lack of agreement can come about in a number of ways. One of the more common is when someone relates an event that they themselves did not witness but learned about from another.

There is also the element of interjecting an extra layer. A prime example is seen in the survivor account of James Gee. He was a Marine on the USS HOUSTON and was moved to Burma as part of the Fitzsimmons Party. His memoires were published by family members after his death. He would not have been present for the final edit to clarify any elements of the story.

In the version of the story of the bombing of the ship carrying the US POWs to Burma told in his book, it is the American POWs who are drowning the Japanese soldiers in the water. This is blatantly incorrect! There would have been no US POWs in the water! They were Dutch POWs on the ship that was sunk. Other accounts relate them telling of killing the Japanese who were in the forward hold of the sunken ship after they were brought aboard the ship carrying the Americans. Gee was not present at this event. He was already in Burma with the earlier group. He obviously heard the story retold. Whether he substituted his fellow POWs for the murderers or his family mis-remembered his version of the story is unknown. It does, however, hilite the errors that can enter a saga as it is pieced together. Before it can be safely integrated into the saga, there is a need for corroboration. I blame the publishers and editors of these books for not properly vetting the story as it is presented for publication. This book wasn’t published until 2018, so there were many other accounts of this event already available. They simply did not perform their due diligence, before accusing Americans of murder, a war crime.

It is also worth noting that even the accounts of those who actually witnessed an event can vary. These variants, such as the description of the gunboat that was escorting the two POW Hellships, do not invalidate the story just interject a level of caution that is necessary before we rush to link puzzle pieces together to develop a clearer picture of any given event.

[1] Some official military documents state he DOD as 7 MAR’ still prior to capitulation