Two of the most unique books about the TBR are that written by one of the Japanese Railway Engineers who oversaw the building of the railway and an Australian account centering on post-war events.

Other major contributions come via British and Australian authors:

A review of Ltc Owtram’s book; in it he describes his time at NongPlaDuk and then ChungKai where he interacted with Khun BoonPong:

https://media.defense.gov/2021/Sep/13/2002852443/-1/-1/1/MARTINO.PDF

Rohan Rivvett’s book BEYOND BAMBOO provides some unique insights to the Burma Sector POW experience:

As a non-military, Australian war correspondent RIVETT was perhaps poised to provide a different perspective on his TBR experience. He was added to the rolls of the AUS POWs and was treated as an officer in Black Force in Burma so he had access to much information that the common soldiers, who wrote most of the survivor books, did not have.

He does provide us with anecdotes and facts that I had not seen in other such texts. For example, he details a number of escape attempts and the inevitable death in the jungle or by execution of the would-be escapees.

He provides one of the few listings of the flotilla involved in the Battle of the Java Sea on 27 FEB. In addition, to the HOUSTON and PERTH, he lists the HMAS Exeter and the Dutch cruisers DeRuyter and Java (both sunk). Also lost was the destroyers Jupiter (British) and Witte de With (Dutch); survivors were the British Electra and Encounter along with 5 others unnamed.

He provides us with an estimate of the size of the Nakorn Pathom hospital at a population of 5000 with a peak of 8000. He notes the opening of this facility as APR 1944. He devotes a moderate amount of time to the larger romusha (Tamil) population, but provides only the usual ‘guesstimates’ of the overall population. He notes the severe toll that cholera took in many of the Highlands camps, particularly among the romusha. He places their deaths at 250,000 whereas for most estimates this is the population number. In discussing the 1944 dedication of the Japanese shrine, he notes that it included an admission of 76,000 romusha deaths by a Japanese presenter. That would be at the far lower end of the scale. It would also have been a ‘through 1943’ figure and not include the tens of thousands who perished in the next 3 years.

Another seemingly unique figure he relates is that of 800 combined POW casualties due to Allied attacks on the TBR.

Like most accounts, he spends a considerable portion of the book discussing the dire medical situation. In this he mentions a major Dengue Fever outbreak in Burma in Aug 43 that others do not. Perhaps this stands out in his memory since he was one of the victims. He is also struck by the massive numbers of unburied or unmarked and unrecovered burials that must still be strewn about those jungles despite the huge numbers of cholera victims who were cremated in crude pyres.

My main criticism of his content is that he includes a significant amount of material that he had no first-hand experience with. I’d suppose that it was his background as a journalist that compelled him to write a more complete story of the TBR saga far beyond what he himself had experienced. He writes in such a way that it is often difficult to know if his is speaking from first-hand experience or from knowledge acquire via research. One has to remind oneself that he was working in the Burma Sector so his access to any information about the Thai Sector would have been minimal at best. Yet, he seems to relate it with authority.

LtCol Charles Kappe was a medical officer in the AIF. He was part of F Force sent to Thailand in APR 43 as replacements troops. They suffered the most hardships, depravation and death rate due not in the least to their arrival at their assigned places of work just as cholera broke out in that sector.

Apparently Kappe compiled this account from diaries of his fellow soldiers as well as his own soon after his return to Singapore in MAY 1944. This edition was not published until 2021. The publishers included the following note:

Both Part I and Part II are reproduced in the form that they were originally written. Aside from correcting obvious spelling mistakes or typographical errors, we have strived to keep the edits and alterations to the absolute minimum.

My own editorial comments are as follows: In the ensuring 70 years between compilation and publication, much information has been made available about this topic. While Kappe’s knowledge of his precise whereabouts is better than most memoires, he misnames many of the local places. He also offers the story of the demise of a Lt. DONNES whose true name as per the CWGC is DOWNES. I offer this to define the publishers / editors as lazy in making no effort whatsoever to insert the correct names. There are other minor errors and inconsistencies in this edition, but these are the most egregious.

Having said that, Kappe’s account is indeed one of the more readable and detailed accounts of the F Force trials and tribulations. But the timing (prior to the war’s end) leaves little time for analysis or perspective. He states “no word picture, however vividly painted, could ever portray faithfully the horrors and sufferings actually endured.” He does not overtly state his sources although the level of detail he provides leaves no doubt that he was working from first-person diaries. That these were not all his own is evidenced by details of events that he could not have witnessed.

He opens by relating the promises (lies) that the IJA made about their demand for 7,000 men to move from Singapore to Thailand. These induced the Australians to include 20% who were less than physically fit; for the British that number was 30%. Within weeks they had learned the folly of their decision.

As a result of the Japanese subterfuge, these men left Singapore with everything they owned and everything available to the units to include two full bands! Days later most of those items were being pilfered by the locals from a warehouse in BanPong. 7,000 men had been told that they would be leaving there with only what they could carry. Little did they know that what was in their immediate future was a 2-300 kilometer trek over 17-20 days.

The overall saga of F Force is reasonably well known and need not be repeated here. However, Kappe does provide some insight and facts that I have not seen elsewhere.

First was their route of travel. He describes them as crossing the MaeKlong Bridge and then the WangPo viaduct on foot. Many of the other work parties took a longer route over the Tadan Bridge. He vividly described how this long march took a heavy toll on the less fit men: ”the rate of casualties was such that the position soon would be reached when every fit man would be carrying a sick man’s gear as well as his own.” Somewhat surprisingly, he reports that “there were no fatal casualties during the course of the actual march itself.”

Upon arrival at KonKoita he encounters “Ramil and Burmese coolies”. He also notes the presence of Burmese workers at other camps in Thailand. I have no reason to doubt that he could correctly identify their ethnicity but this is the first reference I have seen to Burmese workers inside of Thailand. It goes without saying that his ”Ramil” coolies were Tamil-Indians from Malaya. Their presence in this sector is well documented.

There is another feature of the overall organization that he was either unaware or simply fails to mention. The 9th Railway Engineer Regiment was responsible for the TBR in Thailand up to KonKoita. Within Burma and about 40 Kms into Thailand that responsibility fell to the 5th Regiment. He simply never seems to note the difference although F Force worked mostly in the 5th Regiment’s area. This is indeed something that would come to light after war’s end.

He goes on to note with much dismay how in these camps near the Thai-Burma border, his troops and the coolies were in very close contact even to the point of having to share the same quarters on occasion. Elsewhere, particularly in the 9th Regiment’s area, the POWs and romusha were housed quite separately.

True to IJA policy, the UK and Aussie contingents of F Force for the most part occupied different camps. But when they were co-located Kappe openly states his disdain for the lack of concern for health and hygiene among the Brits.

Given the terrain and monsoon effects, he states how work on the Railway was often secondary to the building and maintenance of a road way to move men and supplies once the KwaiNoi River was no longer available above Nike at Kilo 280.

He is also the first to describe how “six-wheeled Japanese lorries which were transporting rations from Burma to Nike.” This is but one suggestion of the link to the Burma-based 5th Regiment. He was dismayed that “every day a convoy of empty ration lorries passed the camp on their return journey to Burma” but the POWs were denied access to move either men or supplies. He also describes his relief as a medical officer when thousands of the sick were moved to the newly opened “hospital” at KM 55 in Burma. He also notes that 20 Brits died during that transit.

He provides a large number of charts of the troop strength and medical conditions at various camps. But because they are most often of the AIF troops only they are of limited value in integrating them into the overall TBR data. He does, however, provide one set of data on the AIF portion of F Force:

| F Force | ||||||

| Strength of A.I.F. | 3662 | of the 534 | ||||

| Deaths up country | 660 | 18.0% | 122 | 27.7% | deaths | |

| transit deaths | 232 | 6.3% | ||||

| Missing up country | 13 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.4% | MIA | |

| Remained up country | 534 | 14.6% | ||||

| Returned to Singa | 2233 | 61.0% | 411 | 72.2% | returned | |

| Deaths in Singa | 32 | 0.9% | 0.9% | late deaths | ||

Given his attention to detail and lengthy description of the various up-county camps, I had great hopes that he could fill in some of the ‘missing puzzle pieces’ concerning the location of the F & H forces at Kanchanaburi as they awaited the return to Singapore. Unfortunately, that was not to be. He simply states that since some H Force members still occupied the area that they were destine for, they were moved to “an adjoining camp”. The only other hint he gives as to the location is that it was a mile from the river. Given all we know about the KAN area, this does not fit the description of any known camp.

Overall, his is an easy to read and detailed account of these tragic events. I’d rate it 9/10 – perhaps the highest I have ever given! It could have been even better if the editors had done a bit more research into the details of his saga.

The Missing Years seems to have come about via an odd combination of events. The author is listed as Stuart Lloyd but the content is the memoires of one Capt Hugh Pilkington (aka Pilk) of the 6th Royal Norfolks. He is said to have compiled his extensive notes into a manuscript during his homeward bound voyage in 1945. Pilk’s son delivered the hand-bound manuscript to the author many years later and resultant The Missing Years was first published in 2009.

NOTE: Lloyd does what many editors of such memoires fail to do and attempts to add context to the original manuscript by correcting some of the geography and adding other important world events.

Having said that, the result is hardly remarkable for its content. It provides little in the way of unique information concerning the overall POW saga. Having been felled by a sniper’s bullet in Malaya, Pilk survives the Alexandria Hospital massacre in Singapore despite being confined to bed encased in a plaster body cast in an attempt to save his arm. Throughout the narrative, he relies on his ‘disabled arm’ to secure special handling like motor transport while others walked. He languishes in Roberts Hospital and Singapore until he is swept up into H Force in APR 43. He was one of the large percentage of that group who were anything but ‘fit’. He already had malaria and dysentery as well as early signs of Beri-beri.

His description of the rail journey to BanPong then the trek to Tarsao and on to Hintok is rather typical of that described by so many others. But it is at BanPong that we are introduced to one of the hallmarks of this saga: his menus! I, personally, am someone who can hardly remember what I had for breakfast two days ago. Pilk, on the other hand, spends a fair percentage of his text describing in detail what he had for dinner on any given day! That may be the only unique thing about this memoir.

Arriving at the Malay Hamlet camp with a contingent of H Force, Pilk is soon assigned to work the upper end of HellFire Pass. He provides us with a vivid description of the horrors of that place. By late Sep 43 – prior to the Railway’s completion – the sickest of the Hintok H Force are evacuated to Kanburi. He describes the hospital where he ended up as being “a few yards from the railway”. But that really doesn’t provide any true information as to the geographical location. Perhaps it was the F & H hospital in the Don Rak area; perhaps not. He tells us that 550 men perished there in the latter months of 1943. In early DEC, H Force began its return to Singapore. By his count, of the 10,300 men in the combined F & H Forces, only 5000 returned.

While back in Singapore, Pilk claims to have written any number of short stories. It is not made clear what happened to these. Are they stand-alone stories or were they incorporated into this manuscript? He further claims that the famous cartoonist Robert Searle contributed illustrations for some of those stories, but Lloyd included none in this edition.

My primary interests lie with the TBR POW saga. It’s roughly the middle third of this manuscript that involves the TBR. Pilk continues his detailed menu recitations throughout the manuscript! Perhaps the 2/3 of the story that takes place outside of Thailand might contain some gems of information for those wishing to learn more of the POW experience in Malaya and Singapore.

==================

Ray Withnall spent years researching the Ubon POW camp that included 4 of the US POWs.

He also presents a BLOG:

There is another unique book in this genre. It relates the story of the SS Sawolka Merchant Marines and their time at Hintok:

============================

Major R. Campbell was one of the senior UK Medical Officers deployed to Thailand in JUN 1943 with the expectation that they could assist in alleviating the dire medical situation among the AFLs. Upon his return to Singapore he compiled an after-action report (NOV 45) in which he provides many unique details about the saga of the AFL.

Much of the data he cites is difficult to integrate into the larger picture, but it is worth documenting it. He opens his report with an accounting of the numbers of AFL from different sources; most of which are unverifiable. [see Part 2 below for more information]

He recounts the oft told story of the Japanese Corporal who supposedly related to an AUS Officer that there were 250,000 Malayans and 100,000 Javanese who worked the TBR of whom 170,000 died[1]. This latter figured is agreed to be a huge overstatement. It is generally thought that 100K Javanese were taken from the island but that fewer than 10K (7500?) worked the TBR.

Another source puts the Malay-Tamil number at 80,000 of whom 30,000 died. An even higher estimate of Malay-Tamil deaths is 100,000.

He also notes that some of those laborers arrived in Thailand as late as the end of 1944. It is quite possible that he is referring to those who worked the Mergui Road.

He then goes on to relate some of the lies and subterfuge that the IJA used to recruit these workers (pgs 6-7). Although other sources hinted at such, Campbell describes with confidence how some of the AFL were assigned in small groups to perform maintenance on the lower end of the TBR in Thailand. He agrees that the majority were sent to the area closer to the Thai-Burma border overlapping with the work area of the POW F Force. These workers were arriving at Ban Pong in Apr 43 intermingled with the trains carrying F Force. They then began the 2-300 Km trek via Kanchanaburi and the Tadan Bridge to their assigned work camps. By his report 1/8th to 1/5th of the AFL did not complete that journey.

K Force is said to have included 164 UK POWs, 55 AU, and 11 Du (230 in total). Campbell tells us that included 30 medical officers and 200 ORs.

The bulk of his report (pgs 10-20) relates the dire conditions that they found upon arrival at the AFL camps. As expected be provides a litany of conditions that plagued them that parallels those described by the POWs but exacerbated by the lack of education and military organization among the AFL. While the maladies were the same, the mortality was considerably worst. The Allied POWs suffered an overall mortality of 20-22%. Among the AFL it was double that. Campbell adds that the psychological depression among this group was severe and suicide was quite common. Men would simply wander off into the jungle to die. While recorded among the POWs it was far from common.

For a variety of reasons, he notes that the morality rate from cholera was about 90%. He concurrently states the POW cholera mortality to be closer to 50%, but even that might be somewhat high. The most oft quoted number of POW deaths from cholera is just over 1300. Despite the dreadful impact of cholera he notes that the greatest killer for both groups was dysentery.

He also provides some facts that are not found elsewhere. It seems that the IJA ran a parallel string of ‘hospital camps’ in this upper TBR region with the sickest of both groups being moved away from the work camps. In all cases, very little was available in the way of actual treatments; these were in fact death camps.

He tells us that there was a hospital at the Ban Pong transit camp – Likely established after trains from Singapore stopped arriving. He also notes a grossly overcrowded ‘Coolie hospital’ in Kanchanaburi (1 of 2 apparently) that experienced over 5000 deaths over the course of 18 months – presumably MAY 43 to NOV 44. He says it housed 1500-3300 at any given time, but provides no information as to its exact location.

On page 21, he provide some detailed listing of death rates among some of the AFL groups. These generally are in the range of 50% survival.

He closes out the report (pgs 22-26) by describing the conditions at the various locations where the K Force ‘ministered’ to the AFL. The words ”dreadful” and “appalling” seem to apply universally. These reports include many instances where the K Force personnel were abused and exploited by their IJA masters and forced to perform many duties other than the medical care they were intended to provide. In many if not most camps, they answered to lower ranking IJA personnel with no medical training. He cites a report that 2 of 10 physicians at Tha Mayo died of cholera after they were billeted in a former cholera isolation tent. Unfortunately, the CWCG records no such deaths.

Another fact that is evident in this report but is rarely stated elsewhere is that the largest influx of AFL began in MAR 43. The first documentation via photos that we have of AFL working alongside POWs is at HellFire Pass. Work there began on 25 APR 43. It is possible if not likely that there were small groups of AFL at other points prior to HellFire. There is a brief mention of some working on the concrete bridge at Tamarkam. But LtCol Toosey makes no mention of them. There seems little doubt that the vast majority of the AFL worked at HellFire, Hintok and beyond in the F Force area.

Part 2:

“He recounts the oft told story of the Japanese Corporal who supposedly related to an AUS Officer that there were 250,000 Malayans and 100,000 Javanese who worked the TBR of whom 170,000 died.”

The thing to remember about Campbell’s report is that he finished it in NOV 1945. This was perfect for preserving the direct observations that the members of K Force made which comprise the bulk of it. But I would suggest that it was too close to the end of the war to adequately assess those things he had no direct knowledge of. This includes his comments on the numbers of romusha workers.

I do find it hard to believe that there could have been 100,000 Javanese working the TBR. We have to consider the logistics involved. Moving 100,000 men from Java to Thailand (or Burma) would have been an arduous task. The Japanese had trouble moving barely 11,000 Allied POWs from Java to Burma. How many ships would it have taken to move another 100K men? Would they have passed through Singapore or have been delivered directly to Bangkok? There is a rather incomplete reference in the Mansell documents of a J-26 group being transported by ship from Java to Bangkok, but this seemingly occurred too late to have any real impact on the TBR.

It is also hard to hide, 100,000 people. We have so few references to Javanese from any TBR survivor accounts. Like Weary Dunlop, many of the TBR POWs were captured on Java so we would expect that they could have identified Javanese workers if they encountered them. Perhaps such references are contained in Dutch language accounts that are not widely circulated?

One also has to ask the question of just whom they might have been. Were they purely civilian Java natives such that they would be counted among the romusha or might they have been KNIL soldiers held as POWs. Unlike the other Allied POWs, we also know that the Dutch soldiers lingered in Thailand well into 1946 and even 1947. Political unrest in Europe and the DEI prevented their return. Would not 100K more Javanese have been in the same predicament? Where were they housed in Thailand?

I read a Dutch report that 100,000 Javanese in total were moved from the island but to multiple destinations not just to the TBR.

The lower estimates of 7,500 to 10,000 Javanese romusha on the TBR would have been easier to transport then ‘hid’. They could have been blended in with the huge numbers of romusha in the various Kanchanaburi camps. This also begs the question of no reports of Javanese choosing not to return home and settling in Thailand. I am aware of none. That doesn’t mean that there were none, only that there might have been so few that they simply escaped notice.

Another statement that Campbell got partially right is that another 100K additional Malay-Tamils arrived in Thailand in 1944 – post TBR construction. What he fails to report is that these were the Mergui Road crew!

Campbell does make another rather unique statement that there were Burmese romusha in the border area within Thailand late in the construction phase. This is not widely touted, but it makes sense in that we know that Allied POWs (to include the Fitzsimmons Party of US POWs) crossed the border into Thailand essentially as replacement workers for F Force and the accompanying romusha who were so devastated by the cholera outbreak. We are also told that the Burmese romusha all melted back into jungles so were never consolidated as were those from the south. This latter accounts for the fact that we have little post-construction information on that group.

[1] The story likely originated with this report.

Who knew?

As one can see in the excerpt below, this is a poorly written text, replete with errors:

Eduardo Martinez has done a masterful job of collecting the seminal works concerning the US TBR POWs. His memorial webpage to his POW father Homero is found at:

Presented here is his list of references:

Memoirs and Accounts of the Lost Battalion and the USS Houston

Allen, Hollis. The Lost Battalion

Memoir of 1st Lieutenant Hollis G. Allen, one of the 28 commissioned officers of the 2nd Battalion, 131st Field Artillery. Jacksboro, TX. Leigh McGee, 1963. Get Book

Charles, H. Robert. Last Man Out: Surviving the Burma-Thailand Death Railway: A Memoir

Memoir recounting the unimaginable brutality of the camps and the inspiring courage of the men from U.S. Marine H. Robert Charles, a survivor of the USS Houston. An extraordinary account of the role of Dutch doctor Henri Hekking in aiding the survival of the Lost Battalion and USS Houston men in POW camps. Austin, TX. Eakin Press, 1988. Get Book

Crager, Kelly E. Hell Under the Rising Sun: Texan POWs and the Building of the Burma-Thailand Death Railway

Grueling yet inspiring account of building the Thai-Burma railway; includes interviews with Texan POWs. College Station, TX. Texas A&M University Press, 2008. Get Book

Daws, Gavan. Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs of World War II in the Pacific

Australian writer Gavan Daws makes a valiant attempt to compare and contrast the treatment od allied POWs across the region occupied by the Japanese. He seems to have done next to no independent research, instead drawing on and collating the works of many others. Not surprisingly his work adds little to overall knowledge of the POW saga.

Dunn, Benjamin. The Bamboo Express

A true account by a Lost Battalion soldier of HQ Battery who was imprisoned by the Japanese. Chicago, IL. Adams Press, 1979. Get Book

Without going into great detail, this is one of the best written, easy to read, well documented survivor accounts. I was particularly impressed as to his ability to name names and place certain men in certain places at certain times. Obviously a lot of work went into preparing notes BEFORE the writing began. It is also available as an ebook as well as print edition.

Fillmore, Clyde. Prisoner of War

A personal account from 1st Lieutenant Fillmore, Lost Battalion survivor, about his experiences in prison camps and building the “Death Railway”. Quanah, Wichita Falls TX. Nortex Offset Publications, Inc, 1973. Get Book

Fujita, Frank ‘Foo’; Falk, Stanley L., and Wear, Robert. Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun

Fujita, Frank ‘Foo’; Falk, Stanley L., and Wear, Robert. Foo: A Japanese-American Prisoner of the Rising Sun. Denton, TX. University of North Texas Press, 1993. Denton, TX. University of North Texas Press, 1993. Get Book

Fung, Eddie. The Adventures of Eddie Fung: Chinatown Kid, Texas Cowboy, Prisoner of War

A second-generation Chinese American born and raised in San Francisco’s Chinatown reinvents himself as a Texas cowboy before going overseas with the U.S. Army. Eddie was a member of the Lost Battalion’s F Battery. Seattle, WA. University of Washington Press, 2007. Get Book

Hornfischer, James D. Ship of Ghosts: The Story of the USS Houston, FDR’s Legendary Lost Cruiser, and the Epic Saga of Her Survival

Brings to life the terror of nighttime naval battles until their luck ran out during a daring action in Sunda Strait. Survivors of the battle ended up in prison camps with the men of the Lost Battalion. New York, NY. Bantam Books, 2006.

La Forte, Robert S. and Ronald E. Marcello. Building the Death Railway: The Ordeal of American POWs in Burma, 1942-1945

22 interviews with American survivors, beginning with their capture and ending with their liberation. Wilmington, DE. Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1993.

Charles Mott has one of the most unique stories of all the US POWs as told here:

W.F. Matthews also had a seemingly unique journey although poorly documented:

Monday, Travis. W.F. Matthews, Lost Battalion Survivor: The True Story of a God-and-Country American

Some books are just not worth writing. Unfortunately LOST BATTALION by Travis Monday is one of those. It purports to relate the POW experience of W. F. Matthews; it falls woefully short. Ironically, Monday even states so in his preface (Pg 3): “The story of this book consists of an imperfect attempt to tell the incredible true story of an America hero.” [emphasis is mine]. One could hardly find a better word than imperfect to describe this effort. At barely 97 pages of text the book is thankfully short and easy to read. Of those pages, perhaps 17 pages are unique to Matthews. Monday makes extensive use of the survivor accounts of Kyle Thompson and Frank ‘Foo’ Fujita and a few others to tell his woefully inadequate portrayal of the LOST BATTALION story.

This is exceedingly unfortunate in that W. F. himself had one of the most unique POW journeys of any of the 2/131 members.

In short, Matthews was a member of E Battery that stayed behind at Surabaya as the remainder of the Battalion moved west. But Monday does an incredibly bad job at relating the unique journey that Matthews took. In fact, he is completely wrong in some of the most important aspects of that journey. Matthews had been wounded by shrapnel during E Battery’s ill-fated defense of Surabaya. Those wounds though slight, became infected and when the bulk of E Battery was moved first to Batavia (Bicycle Camp) in June 42 and then on to Japan (Nov 42), Matthews was in the hospital so missed that movement.

Monday claims to have garnered most of his information about Matthews’ unique story in a 2003 interview. He did a terrible job of detailing that journey. Matthews claims to have still been in the Surabaya hospital in Feb 1943 when PVT A. Hernandez died of TB there and to have participated in his burial. He relates that there with him were Captain Thomas Dodson, the E Battery commander, as well as a ‘Gil’ Carter, Cecil Lofley, and W.F.’s friend “Red” Shields. Here is where faulty memories and errors creep into the story and then multiply. There was no POW named Gil Carter; apparently Carter’s name was actually Uell Maples (nicknamed “Banjo”). CPT Dodson is referenced in other records as having arrived at the Bicycle Camp in October 1942 and being sent to the POW camp in Manchuria. He should not have been in Surabaya as late as FEB 1943.

Matthews claims to have arrived at the Bicycle Camp in Mar 43. He makes no mention of approximately a dozen other E Battery members who had been left behind there when the bulk of E Battery departed for Japan via Singapore. Matthews is uncertain of the date that he departed Batavia for Singapore. On page 70 of this woefully inadequate saga, Matthews claims to have been carried “to Bangkok” by various means of conveyance. He goes on to state that “We were within about 25 miles of Bangkok on that railroad.” and “We were pretty close to that River Kwai where they were building that bridge.” Both of these statements are patently erroneous and should never have passed the editorial test for accuracy! Matthews further claims that he worked loading and unloading freight on the famous Burma-Thailand Railroad. However, “Red” Shields with whom Matthews was a ‘good friend’ is known to have been among the group of US POWs who went from Singapore to the Hintok area in SEP 1943. There were 5 other E Battery members in that Hintok group. Matthews makes no mention of any but Shields.

Unless Matthews had a completely unique POW experience in Thailand, it would seem that he was actually in that Hintok group. However, speaking against that is that he does not appear on the best list of Hintok POWs as presented by Gerald Reminick nor is there any mention of his participation in any aspects of building any portion of the railway. So it seems that since Monday failed to adequately document Matthews’ actual presence in Thailand, we will never adequately define where he was. Monday’s book makes short shrift of this most unique aspect of any US POW. Matthews claims (on page 72) that “as we got up there” (never adequately explaining where ‘there’ was) he worked at ‘farming tapeoka [sic] ’ for a period of 3-4 months. Again, Monday fails to define when or where this occurred. In addition (on page 77), he claims that “while working near Bangkok” he faced bombing raids by US planes. Once again, no details of time nor place are provided. Page 79 states after his time near Bangkok, he returned to Singapore. Now we do know that the Hintok survivors were returned to Changi as a group. So it speaks to Matthews being a member of that group. Matthews and Shields as well as about 10 other E Battery members are well documented as having been liberated from Singapore.

Even though Matthews’ time in Thailand seems to be masked in fog, he most definitely went from the Bicycle Camp to Singapore and returned to Singapore after some time in undisclosed locations in Thailand. I can only fault Monday for not adequately filling in the period of time that Matthews was in Thailand.

Monday also fails to adequately relate the escape and evasion attempts by E Battery members. As their defensive perimeter collapsed just south of Surabaya, E Battery seems to have broken up into three groups. One group, led by Lt. Hollis Allen withdrew into the town and awaited the arrival of the Japanese. Battery Commander Dodson led a group of 50 or so men who boarded a ship at the Surabaya port with the intention of escaping capture. They made it only to the east end of the nearby island of Madura before accepting that escape was impossible. Matthews claims to have been among a smaller group that boarded a smaller boat but abandoned that escape attempt earlier than Dodson and landed on Madura Island as well. There they were quickly rounded up by some Dutch and Javanese soldiers and held in a compound until being turned over to the Japanese. By 10 March, all of E Battery was in IJA hands. At some undefined date, Matthews was hospitalized due to infection of his leg wounds and separated from all but a handful of his comrades.

To say the least, I was profoundly disappointed in the saga as related by W. F. Matthews and published by Travis Monday. Both deserve some blame for not adequately documenting what seems to have been a completely unique POW experience. How any editor worth his position would have allowed such a faulty account of Matthews’ story to make it to publication is beyond comprehension.

Biography of PFC W. F. Matthews, member of the Lost Battalion’s E Battery. San Angelo, TX. Lulu Enterprises, 2004. Reference: https://www.worldcat.org/title/wf-matthews-lost-battalion-survivor/oclc/56883399

British POW John Stewart and Dutch Clifford Kinvig wrote overlapping but riveting accounts of their experiences as part of F Force which had one of the most harrowing journeys of all the many POW groups. Stewart’s account is more personal while Kinvig ranges across the entire Pacific Theater as well as relating his personal experiences. While very readable, his account is more chaotic in its geographical and chronological presentation.

John Stewart served as a technical advisor on the David Lean movie set. He states that in his opinion: “Had it not been for the Lean/Spiegel film, the Death Railway would have been an almost invisible wrinkle in the last World War.” As flawed as it is, it created a yearning for future generations to know more.

Captured on Java, Dutch 2Lt Cornelis Evers waited until 1993 to publish his memories. At just over 100 pages it is a very short account of his years on captivity in Thailand. In fact, he devotes nearly 1/4th of the text to his post-war War Crimes activities. Another odd thing is the format that chose. He writes not in paragraphs in a narrative style but in loosely linked single sentences. Although he generally lays out history chronologically, he changes topics frequently and rapidly. He rarely provides any details to his story, beyond the when and where. He also includes many of the most common anecdotes related by many other. One has to wonder if he did indeed experience all that he relates or is providing what he heard from others. Per his chronology, he was moved from Eastern Java through Singapore then to KinSaiYok on the TBR. From there, to HinDato then to the large Dutch camp at NongPlaDuk 2. After time at the Nakorn Pathom hospital, he found himself at Ubon at the end of the war. I often criticize the editors/publishers for not insisting on more clarity an detail, but it appears as if EVERS avoided such involvement and published his story privately. All in, his is a rather superficial account that adds little to the overall saga.

Alfred Knights’ story of the V Men’s Club

Nussbaum, Chaim. Chaplain on the River Kwai: Story of a Prisoner of War

Portrait of life among allied prisoners of war in Japanese camps, from his diary, his is the saga of a rabbi’s struggle to provide hope and comfort to men of all faiths. New York, NY. Shapolsky Publishers, 1988.

My usual lament about such accounts is how someone can write so much and say so little. AUS physician Rowley Richards managed to do just the opposite. I found it amazing how he describes events in exquisite details, complete with laundry lists of names. He is often short on dates and places but his descriptions are nothing short of vivid. Being a physician, of course, his book is heavy on medical information. He did also add new data as to the COD of a few individuals. His account spans more territory than most from Singapore thru Burma then Thailand followed by Saigon and then Japan. Along the way he survived the sinking of the Rakuyo Maru that took the lives of so many. Perhaps it is an Australian thing, but he chooses to refer to himself throughout the account in the third person by his first name; what ever works for ya!

Thompson, Kyle. 1,000 Cups of Rice: Surviving the Death Railway

Personal account of how the author, as a teenage soldier from rural Texas, became a member the “Lost Battalion” to build the Thai-Burma railway. Kyle Thompson was a member of Headquarters Battery. Burnet, TX. Eakin Press, 1994.

Beattie, Rod. The Thai-Burma Railway: The True Story of the Bridge on the River Kwai

This book presets Beattie’s estimates of the numbers of POWs and romusha and their associated death rates. These have become the most oft cited figures. Beattie, however, presents no information as to how he derived those figures.

Robert Hardie. The Burma-Siam Railway. The Secret Diary of Dr. Robert Hardie, 1942-1945

Robert Hardie was a British POW captured in Singapore in early 1942. Barnsley, UK. Pen and Sword Books, 1988.

Kreefft, Otto. Burma Railway: a visual recollection. Bangkok, Thailand

Sukhumvit Printing Co. Ltd. for the Burma-Thailand Railway (2008).

La Forte, Robert S, Ronald E. Marcello, and Richard L. Himmel, With Only the Will to Live: Accounts of Americans in Japanese Prison Camps 1941-1945

Accounts of 52 individuals from interviews with survivors of captivity covers every stage of their ordeal. Wilmington, DE. Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1994.

Lomax, Eric. The Railway Man: A POW’s Searing Account of War, Brutality and Forgiveness

Memoir of a British soldier who bravely moved beyond bitterness drawing on an extraordinary will to extend forgiveness. Basis for the movie by the same name (The Railway Man) featuring Colin Firth and Nicole Kidman. New York, NY. W.W. Norton & Co, 1995.

Stewart, John. To the River Kwai: Two Journeys – 1943, 1979

Memoir from secret notes kept in 1943 during the building of the Thai-Burma Railway. London, Great Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing, Ltd., 1988.

Boulle, Pierre. The Bridge Over the River Kwai: A Novel (1954)

A fictional account of the Death Railway construction and basis for the popular 1957 movie directed by David Lean. Novato, CA. Presidio Press; Reprint edition, 2007.

A reasonably written summary of the TBR based on material from the Australian War Museum supplemented by the person experience of POW Hugh Clarke. Its subtitle is A pictorial record and indeed it contains 90 photos and maps.

It has a heavy Australian lean is lacking in geographical focus. Its errors are minor and attributable to the generality of its summary nature. Overall, a good introductory volume.

Published in 2014 after nearly a decade of research, Peter Brune’s book, DESCENT IN HELL, is an odd combination of events. Brune is an Australian historian with no direct connection to the TBR and the author of a number of books on many topics.

He draws heavily on published sources but claims to have secured access to a number of unpublished diaries. Part V of the book (nearly 100 of the 800 pages) deals with the accusations of desertion and cowardice by the AIF senior command in Singapore, GEN Gordon Bennet. Indeed, Brune’s sub-title is Fall of Singapore—Pudu and Changi—the Thai-Burma Railway so addressing the action of the AIF Commander is not completely out of step. But it seems more like it should have been the topic of a stand-alone book.

As per the sub-title he does follow in generally chronological order the 1941-42 battles and fall off Singapore, the plight of the men in early captivity then their dispatch to Burma and Thailand to build the TBR. The latter portion of the saga is where my interests and knowledge lie. The TBR portion begins at page 595 and runs for just over 100 pages.

As expected, he tells the TBR story from a fully Australian perspective. Although some minute facts may be original, the overall story has been told many, many times. The “usual suspects” are praised – although Lt.Col. E.E. Dunlop hardly receives a mention. But Brune does not pull any punches in calling out the failures of some of the Aussie Officers. He is particularly hard on various leaders of the F Force that suffered so dearly. He also seems to have little regard for the British!

Overall, even at 800 pages, it is a fast easy read. I’d rate it a 7/10. I wouldn’t quite give it the glowing review that the publisher provides at https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/book/Peter-Brune-Descent-into-Hell-9781741145342

The tales of UK Medical Officer S.S. Pavillard are hard to critique. On one hand it is a well written, extremely detailed account of his life in Malaya, his POW time in Thailand and his post-war repatriation. On the other hand, it is almost too detailed. Seemingly it was written in the 15 years post-war and copyrighted in 1960. He relates dates and places with extreme accuracy[1]. His chosen title is BAMBOO DOCTOR. The extreme level of detail that he provides concerning the most mundane of topics leads me to believe that there was a lot of embellishment going on. I’m not calling him a liar, simply that he takes certain liberties with incidents that he may not have personally participated in. The book, after all, is totally all about him!

I must also give him credit for always seemingly knowing exact where he was and that camp’s relationship to others around it. He is also the only POW to name the crossing of the river beyond KAN as Tar dan (Tadan). But he claims to have made that crossing by barge not via a bridge.

There are, however, certain inconsistencies that are a bit bothersome. In addition to some recurring if subtle mis-spelt words, he refers to the Kanyo cutting as “Hell-Fire Corner” so named due to ”the incessant noise of blasting”. In his defense, he never claims to have actually worked there but rather in a nearby camp. He does commit another pet-peeve of mine, he consistently names people by rank and surname but without a given name. For all of the precise details he furnishes, names are not among them. One of the few that he does attempt to name is L/Cpl R.R. Hutchinson. However, CWCG records spell that name as Hutchison (no first N).

In many incidents he relates numbers of deaths at various camps that the CWGC does not record. He also cites treating 20 cases of cholera at the ThaMuang camp in 1944. This seems rather strange given that the outbreak had burned out in June 1943 and no deaths were recorded from cholera in 1944. Others like the renowned LtCol Dunlop make no mention of cholera in 1944.

He does, perhaps, address one of what I call the ‘missing puzzle pieces’ in that he reports being sent to ThaMuang in late 1943 to expand the camp in anticipation of the POWs being consolidated from the jungle camps. But he never actually mentions it as being a staging camp for those being sent onward to Japan. He notes that ThaMuang peaked at 10,000 POWs. He states that he was in charge of the dysentery ward there from May 44 until well into 1945. But he never mentions the Nakorn Pathom hospital; likely because it didn’t involve him. We know that Dunlop spent some time at ThaMuang that must have overlapped Pavillard’s time there, but no mention of him.

He pats himself on the back for developing a novel method of treating Tropical Ulcer that he claims avoided any number of amputations. He mentions the usual treatments of scraping and introducing maggots but never tells us why his method wasn’t adopted by others. He also claims ignorance of the cause of Blackwater Fever, which every physician should have known. He even suggests that it might be due to inade-quate doses of quinine. In another incident, he describes trying to revive a man struck by lightning by performing ‘artificial respiration’ for a full two hours![2]

He always seems to have ‘some’ drugs available to him; if not always in adequate amounts. This is contrary to most other medical reports. He notes performing an appendectomy with a straight razor and bent spoons! In an ethical dilemma, he notes sometimes giving drugs to ‘married men’ over those without families. Another time, he uses the limited supply of quinine to prophylax a number of men rather than treating one man’s acute case!

Elsewhere he notes the loss of some 2,000 of his comrades in the sinking of the Rakuyo Maru in SEP 44, but never actually names that ship. This is such a well-known incident that it is hard to believe that by 1959 he did not know that name!

Oddly enough, via the Mansell documents, there is a record of the camps that Pavillard was assigned to that precisely matches his story. I note this only in that that record seems to be unique among the over 15,000 POWs I have investigated! His description of the PratChai camp (from which he was liberated) exactly matches that of other British POWs.

Pavillard claims to have had extensive dealings with BoonPong, which is entirely possible. But he goes on to mention two names of men in his supporting network[3]. These are a Herr Singenthaler and Tanner of the Swiss Consulate. Again, these are unique to his account as far as my readings are concerned.

In what is obviously information that he encountered post-war, he tells us that there were plans for Allied landings Thailand and Malaya scheduled for SEP 45. I’ve not seen this tidbit of information elsewhere. These would supposedly resulted in the wide-spread execution of the Allied POws.

In short, this man either had the most phenomenal memory of his experiences or the most voluminous diary in existence.

Knights re-visited

Pavillard’s mention of the Tadan crossing inspired me to re-visit LtCol Knights’ account of his POW time. This is where I had first encountered mention of the Tadan route to Tarsoa. Somewhat surprisingly, Knights too notes that upon arrival at Tadan, his group also crossed by barge.

Tadan and LatYa have deep historical links. This area was the commonly used invasion route by the Burmese whenever they entered Siam. There had been a garrison of Thai troops stationed at LatYa dating back centuries. Indeed, today this is the HQ of the 9th INF Div and the largest military base in Thailand. Reportedly, this route was selected due to a numbers of places where the MaeKlong River could be forded. Is it possible that the map denoting a bridge at that point was more of a representation of a convenient crossing point rather than an actual pedestrian bridge? The simple fact that a modern bridge exists there today is not proof of a 1940s bridge.

It is also reported that the IJA Engineers surveyed the Tadan and LatYa area as a possible site for the railway to cross the river before they settled on Tamarkam.

It was also in Knights’ account that we have the most information about the V Men’s Club activities. Knights mentions no names, but does link the Swiss Consulate to that organization and both open and clandestine efforts to provide supplies to the POWs.

Per the Swiss Society of Bangkok[3] website:

Mr Siegenthaler und Mr Tanner were both founding members of the Swiss Society Bangkok (SSB) in 1931. According to archive documents they both remained active participants at the SSB until 1943. Mr Siegenthaler was Consul at the Swiss Consulate in Bangkok, the occupation of Mr Tanner is not known. At that time many Swiss in Bangkok worked for one of the Trading Companies, such as Diethelm, Beerli Jucker or Züllig. There are no records of the SSB between 1944 and 1948. The first documents after the war appear in 1949

[1] One criticism I have often voiced is the failure to ’edit’ one memories to properly identify the geography.

[2] Modern CPR techniques weren’t developed until the mid-1950’s

[3] The V Men’s Club https://www.ssb.or.th/about/history verifies Siegenthaler’s presence!

==========================

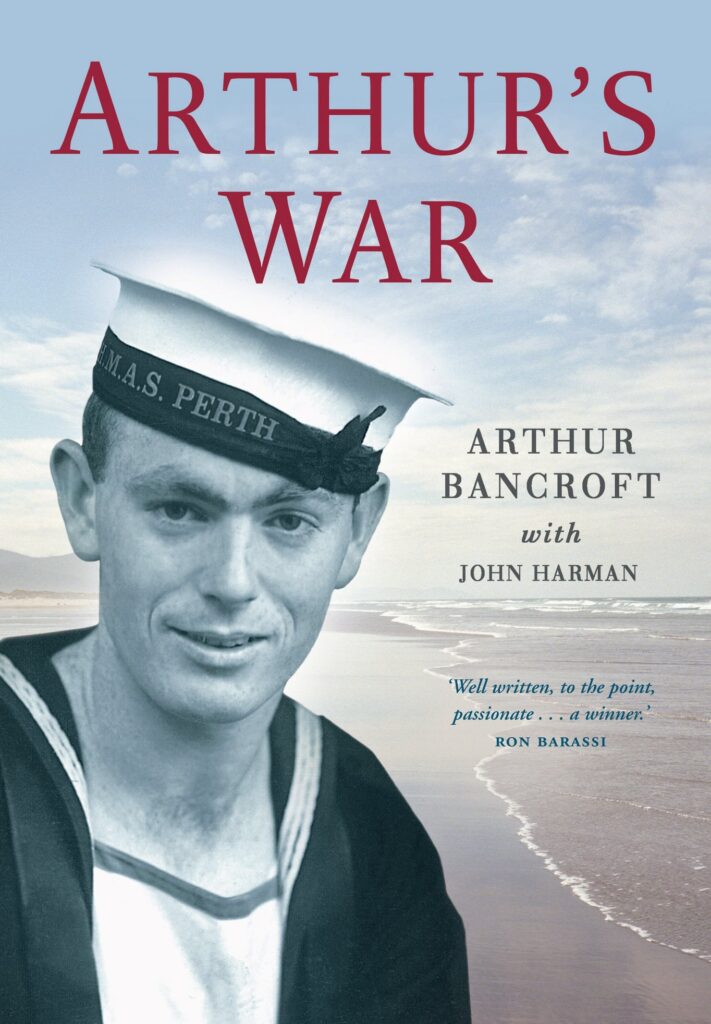

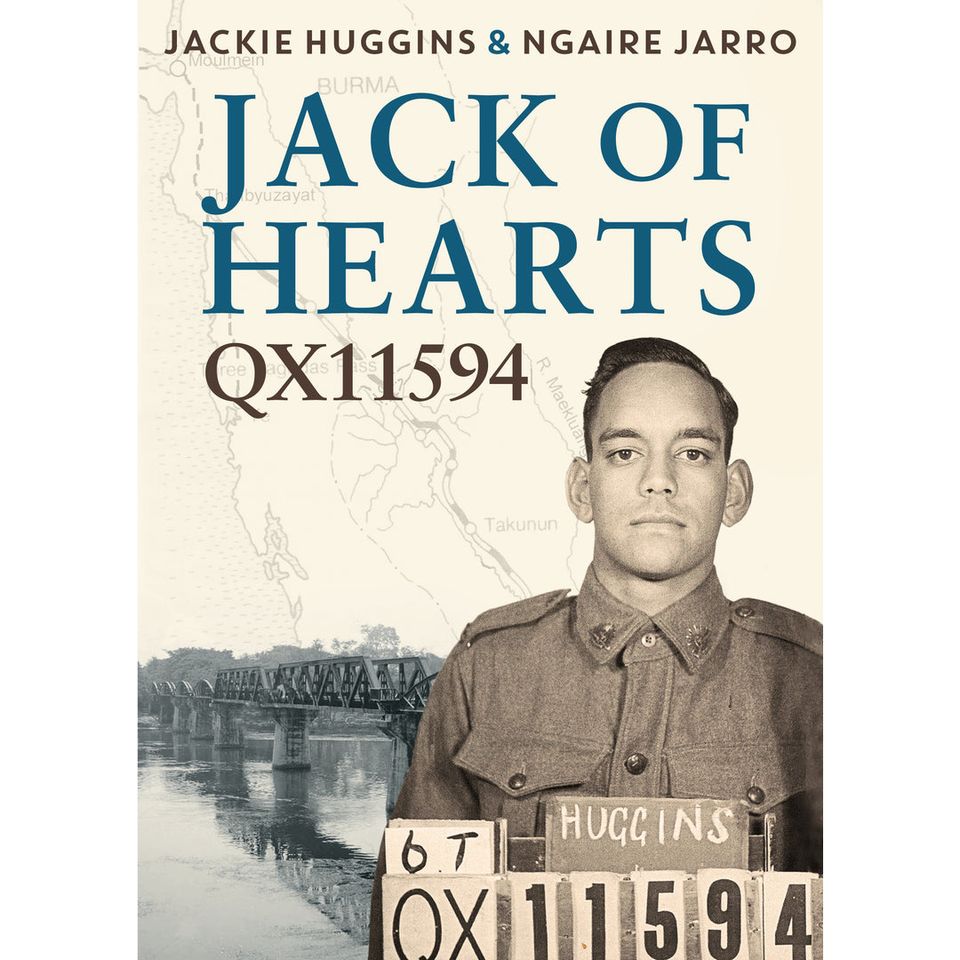

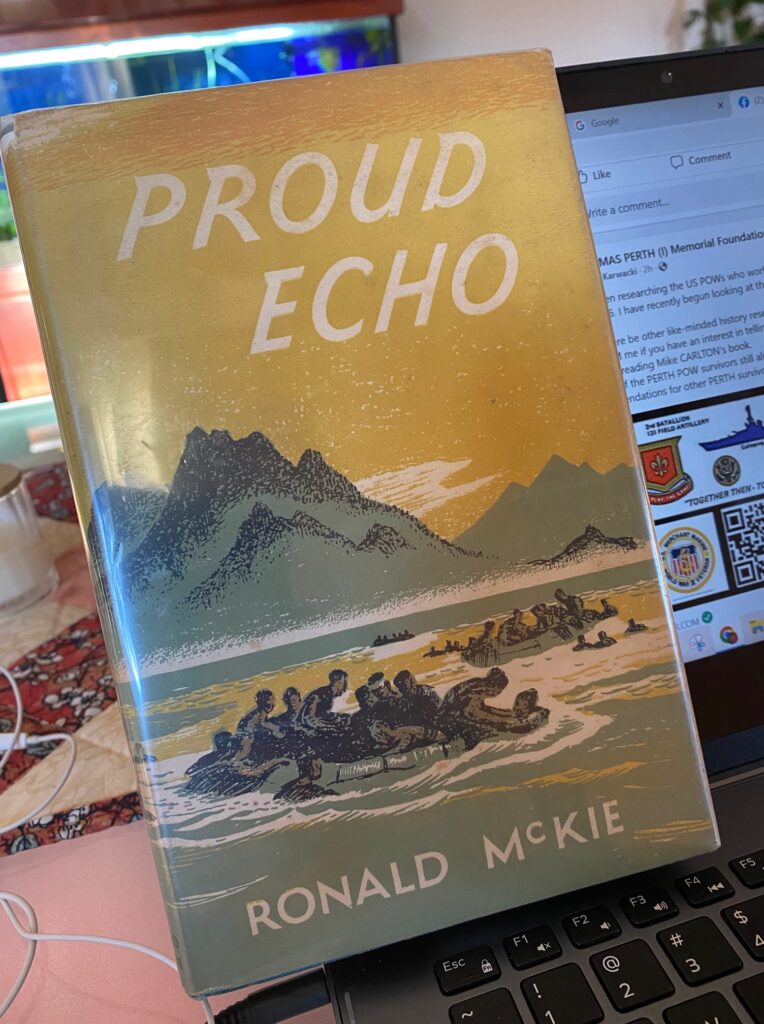

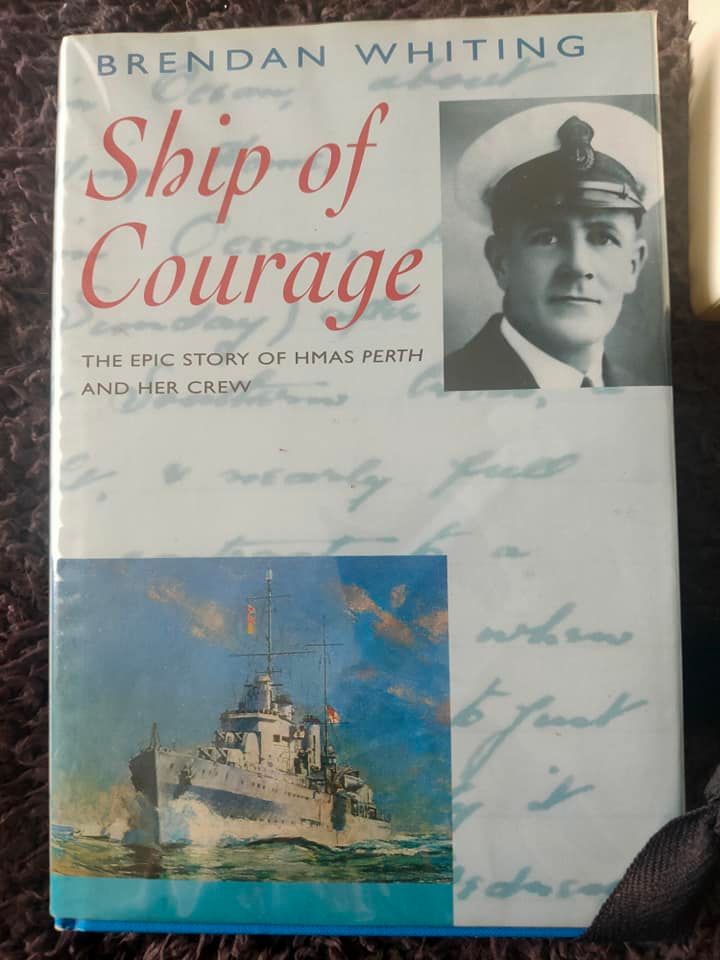

The PERTH Section of this website [# 27} draws heavily on the content of three books about and by survivors:

Other texts by PERTH Survivors:

Sections 10.3 Thai Monarchies and 10.4 Thai Democracy are heavily dependent on:

Some facts on the Seri Thai Resistance Movement were extracted from:

===========================

Two books about the Thai TBR-era in and around BanPong by Dr. Chanwit Kasetsiri:

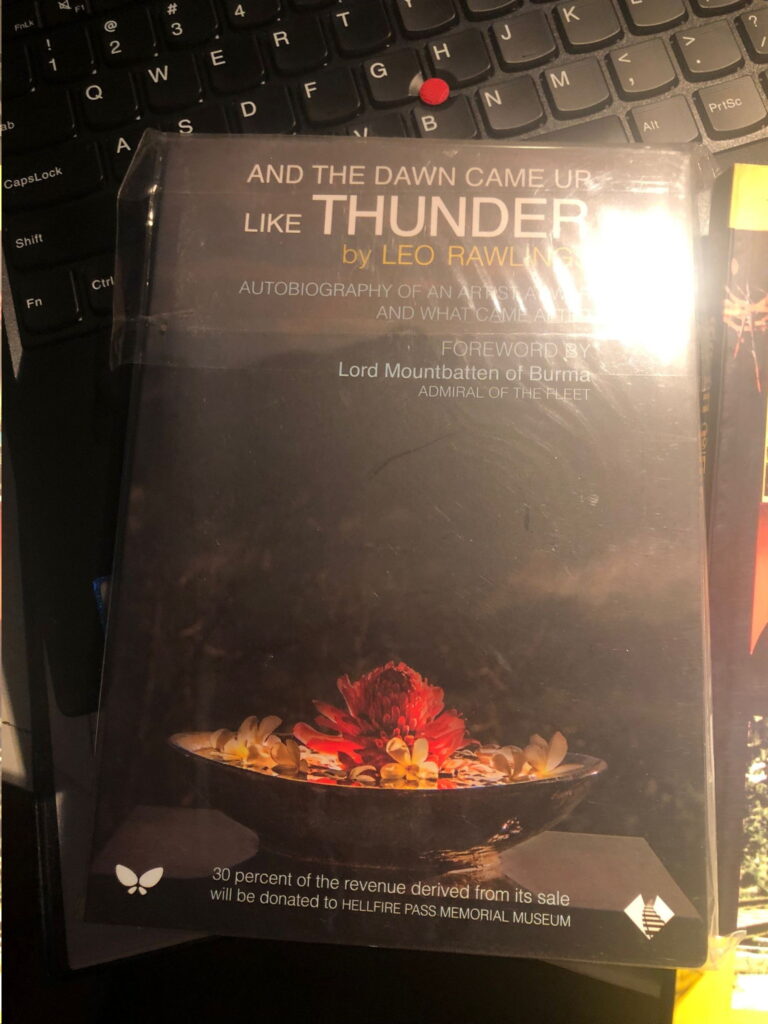

No exactly surprising, but there are also books written by a few of the romusha survivors in both Tamil and English language.

Other lists of POW-related books can be found at:

https://www.cofepow.org.uk/books-cofepow

http://www.usshouston.org/library.htm

https://www.pows-of-japan.net/books.htm

An excellent list of on-line texts is available at

https://www.pows-of-japan.net/books.htm

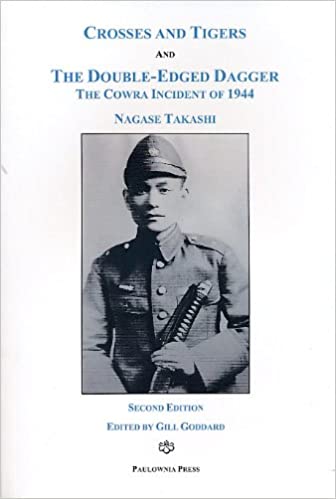

Another rare book selling for nearly $US 200 with only 1 non-committal review on the AMAZON book site. The author was the translator portrayed in the Railway Man who later came to regret his involvement in this project.

29Wa Survivor Genre

Books by and about the TBR generally fall into two genre. The most plentiful are the personal survivor accounts. These are by definition somewhat limited in their scope. Any one person can only speak to what he experienced. For the most part no individual had much of an overview of the situation. Many times the men had no idea exactly where they were nor how their experience fit into the project as a whole. Survivors get into trouble when they try to expand the scope of their text by including incidents to which they were never privy. Mostly these would have come from stories exchanged between the various groups as them were consolidated post-construction. As to the errors that creep into these books because of faulty memories, I blame the editors/publishers for not doing their due diligence on the content.

The second genre are the more analytical books. These are generally authored by historians but a few TBR survivors crossed over into this area as well. These books rely on compiling firsthand accounts with information derived from various official records.

I have recently come into possession of a book that defies categorization. It is presented as the recollections of USMC Private James Gee, a survivor of the USS HOUSTON. But it was published in 2018 under the name of a USNAVY nurse. The Forward relates that she had encouraged Gee to write about his experiences on the TBR as a means to address his PTSD. Gee had died in 1993. Following that nurse’s death some years later the manuscript was found in her attic. The book as published was compiled by a third party who lists herself as ‘editor’. She apparently enlisted the assistance of Gee’s son for some clarifications and additional information. So here we have a manuscript undergoing editing nearly 75 years after it was written by individuals who have no firsthand knowledge of the events in question.

Assuming that the words are by and large those of Jimmy Gee there are some odd aspects about his presentation. In some ways it is written more as a screen play than a memoire. He includes a lot of quoted conversations rather than a simple narrative. He also touches on a lot of information that he as a lowly USMC enlisted man would hardly have been privy to. In a few instances, he even seems to offer an insight into what was happening on the Japanese side of the tale. Was he dipping into a more analytical area here? Using other sources of information that he had no access to at the time? He also includes a myriad of tiny details that a screenwriter might include to ‘humanize’ the story as opposed to a more documentary style of writing. There is no way to know how much of the published text is truly from Gee’s original text and how much was added by the editors. The Forward does suggest that some of what Gee included in this account was gleaned from therapy sessions with other survivors.

Another ‘flaw’ in this account – also admitted to in the Forward by the editor – is that some of the names have been changed. The problem being that no attempt is made to identify these now fictional men. The first we encounter is a man named SHORT. No mention is made of a first name, rank, branch or even nationality, although he is presented as a fellow crewman. He is described as dying at the Serang theater where we know many POWs spent the early days of their captivity. Official documents note the death of two HOUSTON crewmen at that site; neither was named SHORT. One can only speculate as to why Gee or the editors may have seen the need to make such changes. Perhaps Gee could not actually remember the name of the man who died or maybe the editors made the change in anticipation of some sort of liability issue. It simply detracts from the historical accuracy of the document.

None of this detracts from the overall value of the book as it details the experience of a HOUSTON survivor; even one who seems to have a phenomenal memory of dates and names. He includes numerous details like being guarded by 12 IJA soldiers. Why would he have precisely remembered such a minute detail? Consistently he relates the menu of meals he had been served years before. How much was factual and how much just literary license? It must be remembered that he was writing this as therapy not as a factual history!

All things considered, I think that this is the LEAST informative account I have read. I suppose it also begs the question as to who profited from the proceeds of the sale of this book.