How it began (for me)

My quest to learn the history of the men of the Lost Battalion began with the District 5 VFW monument to them which was placed at the bridge in 1997. I had been told that the figures on that plaque were incorrect: that 365 men had not indeed died on the TBR. But how many had and what was their story?

I moved to Kanchanaburi in 2015 and soon thereafter began a quest to learn whatever I could about these men. I started with the Lost Battalion Association’s roster and proceeded to amass a spreadsheet listing each man and his vital data. I used the ANCESTRY.com software to document their births and deaths as well as to access the vast amount of military data that was available.

In communicating with the LBA, I was provided a copy of an annotated roster compiled by LTC Tharp himself and this became the basis of my study of the TXNG portion of this group.

USS HOUSTON Saga

The light cruiser CA-30 was forward deployed to the Philippines in November of 1940 as the flagship of ADM Thomas Hart. Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, she was re-positioned to Darwin Australia as part of American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) naval force headquartered at Surabaya, Java in the Dutch East Indies under the command of Dutch Adm. Doorman.

She participated in convoy protection duties in that area until Doorman sailed with his tiny fleet of cruisers and destroyers to interdict the invasion fleet sailing towards Java. The ensuing Battle of the Java Sea was one of the larger naval engagements of the war. Although there were no battleships employed by either side, the 8” guns of the cruisers were deadly effective. During this engagement, however, it seemed to be torpedoes launched from the destroyers that caused the loss of most ships.

One of the major deficiencies that plagued the Allied naval forces all across the South Pacific was the lack of air cover. [see the story of HMS Prince of Wales at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Prince_of_Wales_(53) ] The Japanese, however, had large numbers of planes in the air based out of Borneo.

Earlier while escorting a convoy to Timor (4 FEB 42), a bomb struck the Houston’s rear turret #3 killing 47 of the crew. Despite that damage, she sailed into battle with the larger Japanese invasion force. During that encounters, she also took some naval gunfire hits and Doorman ordered her and the Australian Cruiser Perth to withdraw for repairs. Because the Allied fleet was heavily outnumbered, he could not afford to dispatch any destroyers as escorts. Soon thereafter, ADM Doorman was killed as his flagship cruiser the HNLMS De Ruyter was sunk.

The Perth had suffered hits on her steering and was unable to proceed at full speed. As the two ships made their way to the western tip of Java at the Sunda Straits, they encountered a flotilla of Japanese destroyers that were quickly reinforced by 2-3 cruisers. In an intense but short battle on the night of 28 FEB 42, first the Perth and then the Houston succumbed to repeated torpedo hits and sank. CAPT Rooks was killed when a shell hit the ship’s bridge just after he gave the order to abandon ship.

Of the crew of just over 1000, about 500 are thought to have made it off the ship but only about 370 made it ashore on Java. All were rapidly captured by the Japanese forces that had landed on the north-west coast. Lt(jg) Francis Weiler was the first recorded Navy POW to die on Java succumbing to wounds received during Houston’s last battle.

According to Australian Maritime records, the crew of the HMAS Perth suffered somewhat worst. 324 of her 671 man crew survived the sinking of whom 106 died as POWs.

Over the course of the next few weeks, the Sailors (334) and Marines (34) were moved to what became known as the Bicycle Camp. Shortly thereafter they were joined by the 568 members of 2 Bn 131 Field Artillery.

At this point, the stories of the US POWs becomes merged. The Japanese had a policy to segregate their prisoners by nationality, but they tended to ignore their branch of service. As the American POWs were moved – along with many of the captured Dutch – from Java to Singapore and on to Burma to work the Thai-Burma Railway, the fate and saga of the 685 prisoners who ended up there was intertwined.

Between May and Sep 1943, 33 Sailors and Marines died while laboring on that railway in Burma. Another 26 died as POWs after completion of the Railway on Oct 1943. In all, 62 Sailors (of 272) and 4 Marines (of 27) died while POWs on the TBR.

There were 21 US NAVY Officers who survived the sinking of the HOUSTON. Most were junior officers: ENS & LT(jg). Of those, 8 worked the TBR. Most of these Officers were separated early on and send directly to Japan. During this period, LTC Tharp refused to be separated from his men and for whatever reason the Japanese acquiesced.

Most of the 11 non-TBR POWs remained in the US NAVY after the war; only 2 of the TBR POWs stayed. By the time they left the NAVY (most retired) 3 had achieved the rank of RADM; 5 CAPT and 2 CDR. The Senior Marine survivor was 1SG Harley Dupler who was one of the first to die (of dysentery) after reaching Burma.

A few dollars more

You’re a teenager in north-central Texas between the OKLA border and Dallas in the late 1930s, early 40s. Your High School is visited by a recruiter who offers you a chance to earn $2 a month for spending 1 weekend in the Texas National Guard. You are now a member of the 131 Field Artillery Regiment. Stir a bit of patriotism into the mix and boys all over Texas hearing the same message are signing on. A weekend of military training is a vacation compared to the ranching and farming chores most are used too; and that $2 comes in handy! It’s enough to take a girl out on a date.

For some families in the North-Central Texas area enlisting in the TXNG was a family tradition. The 131 FA Rgt had fought in WW 1 and much of the equipment they had in the late 1930s was of that era. Boys followed their father’s and grandfather’s path into weekend military service.

Fast-forward to the spring of 1941. Europe is lost the Nazis; England is hanging on alone. Word is sent to dozens of small towns across Texas: The TXNG is being mobilized to form the 36th INF DIV. From all across the State, convoys head for Camp Bowie in East-central Texas as the Division beings to take shape. Regular Army soldiers are added where needed to round out the rosters of the various units. After a bit more training, the 36th heads east to participate in the Louisiana Maneuvers. The 2nd Battalion, 131 FA is cited for proficiency in that exercise. However, upon returning to Camp Bowie, the 36th undergoes a re-organization. It shifts from a “square” division to a “triangular” one; meaning that where there had been 4 units there would be only three. The 2/131 is declared as “excess” and detached from the 36th. But rather than being deactivated, they are handed orders for an overseas deployment. Over the next few weeks there is a lot of shuffling that takes place. Older men and those with children are transferred out and replaced by young, single men from other parts of the regiment. Regular Army personnel arrive to fill vacant positions. They and their World War I vintage, French-designed 75mm cannons are loaded on a train and they find themselves in San Francisco.

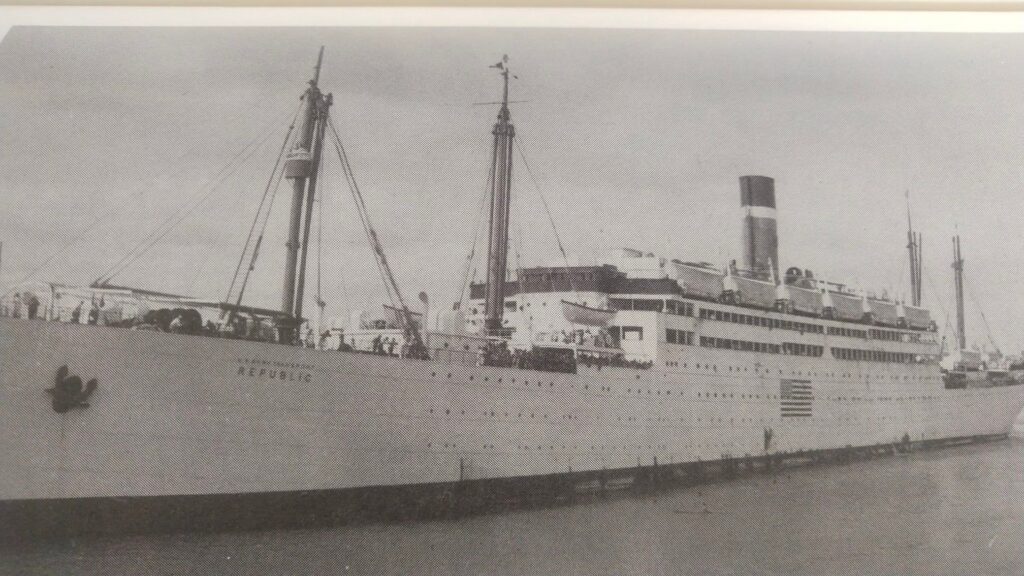

There they boarded the freighter SS Republic for a “secret” destination. The men are convinced that they are headed for the Philippines. [The code word used for their destination is PLUM which translates to Philippines, LUzon, Manila, but they seemingly did not know this for certain.] They had an early Thanksgiving dinner in SFCA before sailing to Pearl Harbor for a refueling stop and heading back into the Pacific. They also load ammunition for their guns for the first time.[some suggest that 105mm guns were added but this is only anecdotal.] In mid-transit, word of the attack on Pearl reaches them. This is followed soon thereafter by new orders: they are headed to Australia! One more refueling stop and they have Christmas dinner in Brisbane.

Just after the first of the year, they board a Dutch cargo ship and a few days later are off-loaded at Surabaja on the Dutch East Indies island of Java. Their orders are to support the Dutch defenders. But in January 1942, there isn’t much for them to do as yet. The Japanese had launched attacks all across the Pacific. Singapore was about to fall (15 FEB 42) and the PI soon thereafter. The Japanese have landed on the island of Borneo to the north, but all is quiet in the southern tier of the Dutch East Indies islands.

The Battalion is detailed to support a squadron of B-17 bombers at an airfield at Singosari just to the south of the port and he convoys the battalion there. The bombers had evacuated from the PI but had had to leave their ground crew behind. They had some bombs and ammunition available via the Dutch but were mainly flying reconnaissance missions monitoring Japanese naval activity in the Java Sea. The artillerymen begin to act as ground crew. Some volunteer to fly as gunners on the aircraft. On 3 FEB, the 131 suffers its first casualties as one of the B-17s is shot down with 2 soldiers aboard.

As the Japanese invasion fleet approaches Java in late Feb 1942, Tharp allows about 2 dozen of his men to depart with the B-17s for Australia. He leaves E Battery to defend the port and moves the rest of the battalion westward to join up with the Australian and Dutch defenders. This “Dutch Army” is composed mainly of indigenous troops under the command of European Dutch Officers. It is actually more of a police force than a combat ready army. Of course, Holland had been overrun by the Nazis in 1939 so these islanders are largely without support or supplies. Add to this this fact that the locals largely resent the decades of Dutch rule and are looking to the Japanese as “liberators” (they will learn the folly of that expectation shortly).

All said and done, the Dutch put up a token resistance and find many of their ‘soldiers’ deserting. On March 8th, they officially surrender the island. The 131 had fired a few volleys in support of the “defense”, but they and the Australians had forced to withdraw to the east away from the advancing invaders. He had them disable their cannons and bury the firing pins in the jungle. They also disabled most of their vehicles to prevent them from falling into enemy hands.

A rumor quickly spread through the unit that the USS Houston had been dispatched to evacuate them from the island. Without substantiation, Tharp agrees to allow few men to go to the southern coast to scope out the chances of departure. They had no way of knowing that the HOUSTON already lay at the bottom of the Sunda Strait. Many other units under the US Java Forces Command were indeed evacuated to Perth; about a dozen 2/131 members were among them as they had been assigned liaison duties at the HQ. [Pace OH 034]

With no hope of evacuation, Tharp holds a vote. Should they disperse into the mountains to the east and try to evade capture or accept their fate as POWs as a unit? Given the fact that Javanese are siding with the Japanese, the men see little hope of any evasion, rather than join any type of guerilla resistance force the locals are more likely to turn them in to the Japanese at first opportunity. After a week or so, a Japanese unit finally arrives and Tharp surrenders his nearly 500-man unit[1]. They spend the next few weeks being guarded by front-line combat troops and are moved around to various places on the island. Finally, they are handed over to special POW guards who are largely Korean conscripts commanded by Japanese NCOs and Officers. They are moved to the capitol city of Batavia (Jakarta, today) and enter the main POW camp known as the Bicycle Camp. It had been the home of a bicycle-borne unit of indigenous defenders.

It is here that they meet the survivors of the USS HOUSTON and hear their story. The 800 hundred or so US POWs are segregated from the other nationalities but are co-mingled without regard to their branch of Service. [This pattern of separation of the POWs by nationality was apparently a policy of the Japanese and would be repeated at all the locations where they held POWs.]

Eventually the camp guards identified those prisoners who were deemed to possess “special skills”. Under the command of Army CPT Zeigler, this mixed group of soldiers and sailors was shipped to Japan via Singapore. Also in OCT 42, a group of about 200 under the command of Army 1LT Fitzsimmons were herded aboard a freighter[2] and sent to the Changi Prison Camp in Singapore. A third and the largest group, labelled as Grp 5A depart Batavia under the command of LTC Tharp on the same ships as the Zeigler Grp. After a short stay there, they, and a large number of the Dutch indigenous troops, were sent by rail to Kuala Lumpur and there they all boarded a 3-ship convoy headed north to Burma.

And so begins the ordeal of the Fitzsimmons Grp 3 and the Tharp Grp 5 as they find themselves in Burma to work the Thai-Burma Railway.

[1] These men became known as the LOST BATTALION in that the Japanese authorities failed to notify any organization of their capture. This was also true of the USS HOUSTON survivors.

[2] Collectively these freighters were known as HELLSHIPs due to the conditions the POWs had to endure.