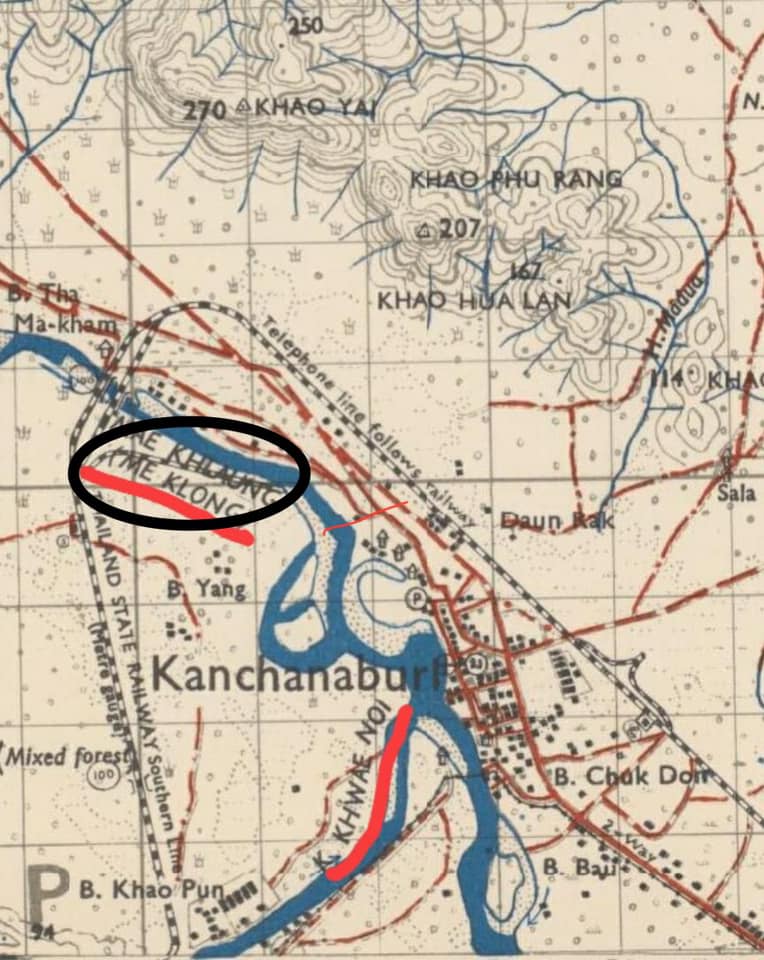

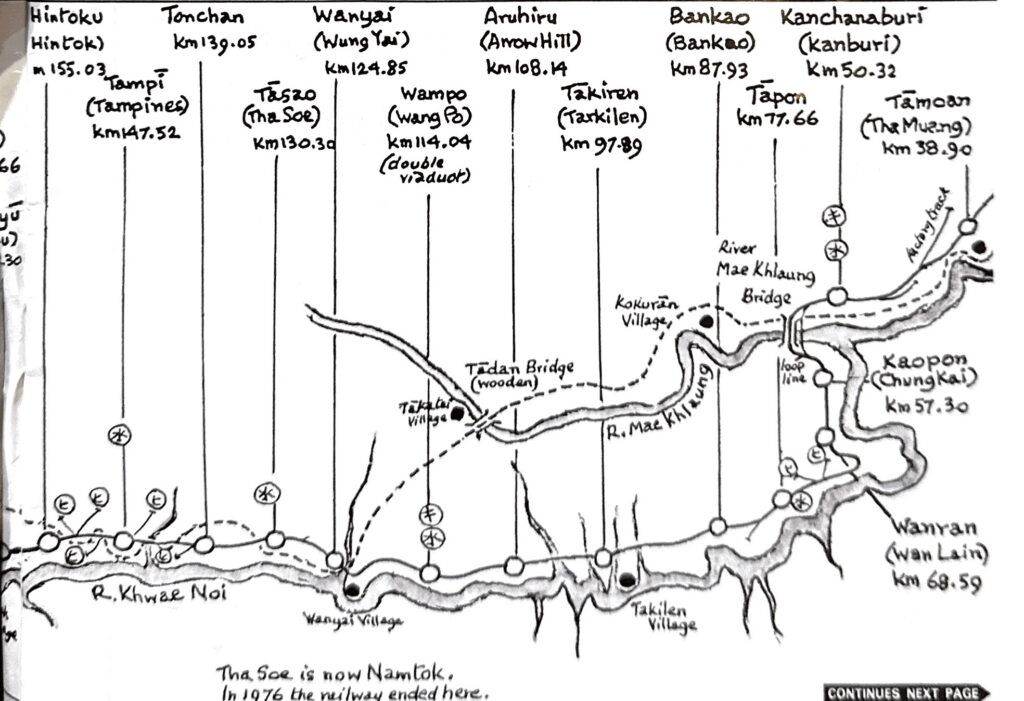

If one looks at a satellite view of that Kanchanaburi area such as seen in the GOOGLE MAPS software, it is obvious that the rails run about 5 Km NW of the old walled city of Kanchanaburi to the point where the bridges were built. Once across the river, the tracks essentially double-back on themselves over that same 5 KM length. The obvious question is: why was the railway lengthen by some 10 Kms? The answer is found in a book written by one of the primary engineers who surveyed and directed the building of the TBR: Across the Three Pagodas Pass: The Story of the Thai-Burma Railway by Yoshihiko Futamatsu (as translated by British ex-POW Ewart Escritt).

He describes how there were three possible routes considered initially. One would have started much farther north in central Thailand in the province of Pitsanulok. This route had been previously explored by German engineers in the late 1800s but was rejected due mainly to the gradient that the railway would have had to cross in terms of the elevation of the mountains that formed the border with Burma in that area. In a straight line distance it would have been a shorter hop to Moulmein, but also would have had to cross the Ping and Moei rivers; the latter being the Thai-Burma Border. It would also have had to use the existing Thai rails from Bangkok to Pitsanulok.

Once that choice was ruled out, the route from Nong Pladuk up to Kanchanaburi posed two alternatives. One would have taken the rails about 10 Km beyond Kanchanaburi city to Lat Ya where it would have turned to cross the Mae Klong (Kwae Yai) River and the turn NW towards the Three Pagodas Pass which would have been necessary to avoid the ruggedly mountainous areas that run north and south in that area. That alternate route would have met the route of the railway as it was built somewhere near NamTok (before Hellfire Pass).

Futamatsu relates that the initial party of Japanese Railway engineers led by a MAJ Hikiji used aerial maps to survey the possible routes and rejected those first two resulting in the one that followed the Kwae Noi River from ChungKai to the Three Pagodas Pass. It then became Futamatsu’s task to oversee that construction beginning at Nong Pladuk.

The reason why the railway took a 5 Km swing up and back is simple geology. The shortest route would have been to turn near the walled city of Kanchanaburi and cross the two rivers at about the point where they converge. But the engineers took core samples and determined that the river bed in that area was too silted to be able to easily reach the bedrock that would be needed for a stable bridge. So they went a bit farther north and found a more suitable site at Tha Mar Kam where the footing was more stable. They also seemed to listen to the locals who described how the Kwae Noi tributary — more so than its larger neighbor — flooded reliably at least once a year. So a bridge near its course would have been subjected to immense water pressure. The Tha Mar Kam site was a bit wider and the banks higher, so there was less of a flooding danger. I’m also sure that the inhabitants of the city were happy that the Allied bombs intended for those bridges were falling 5 Km north of their homes!

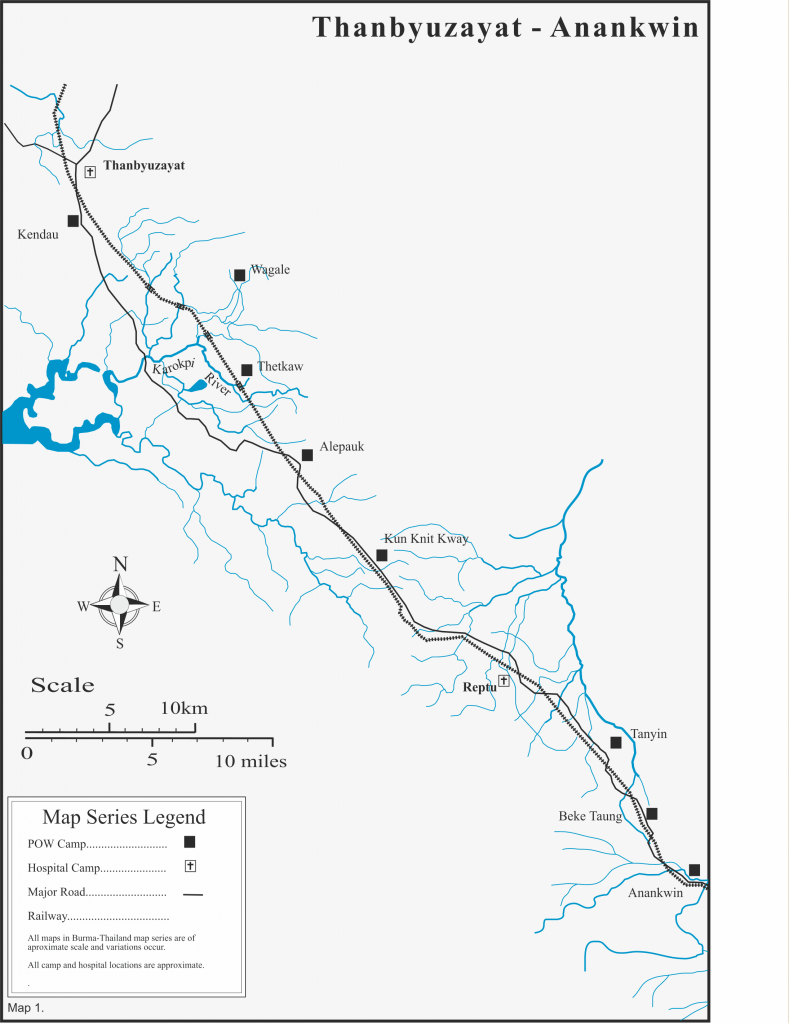

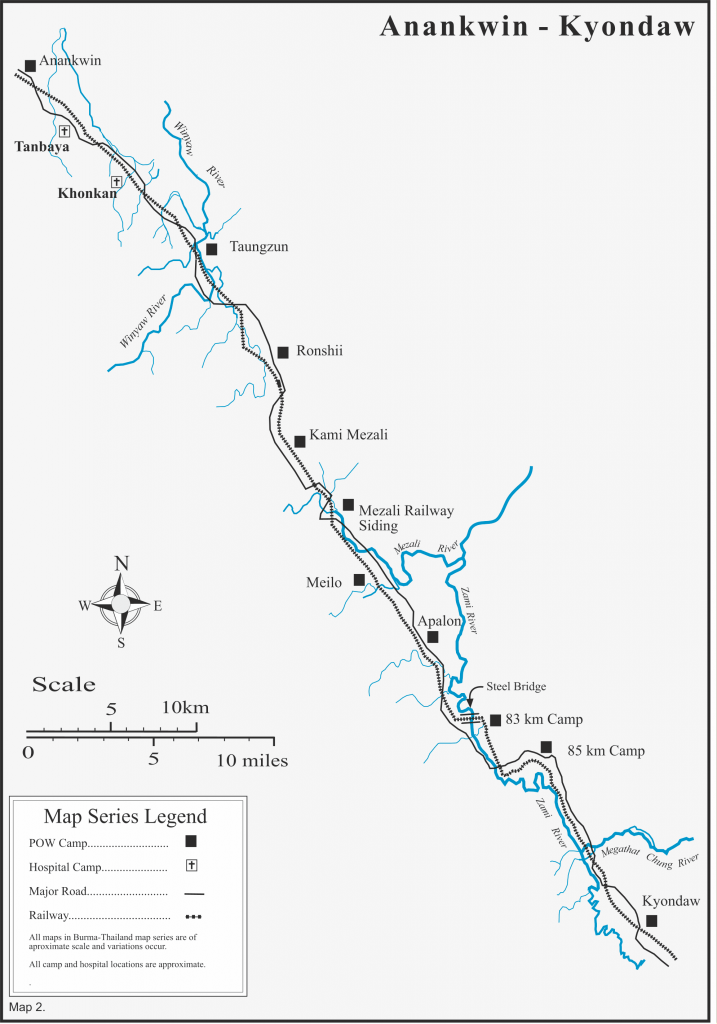

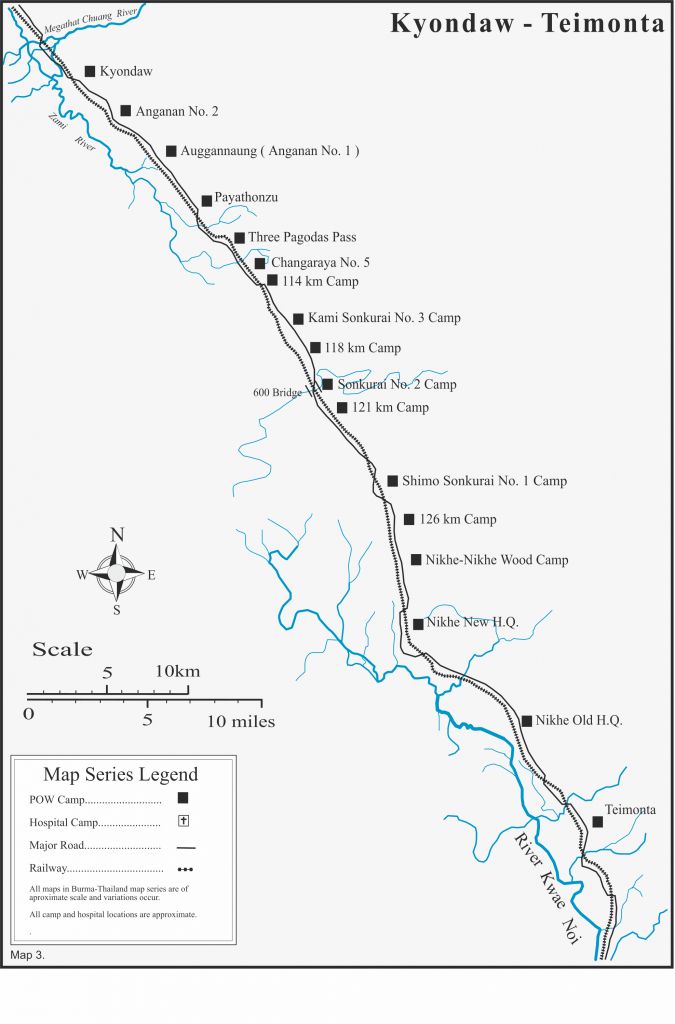

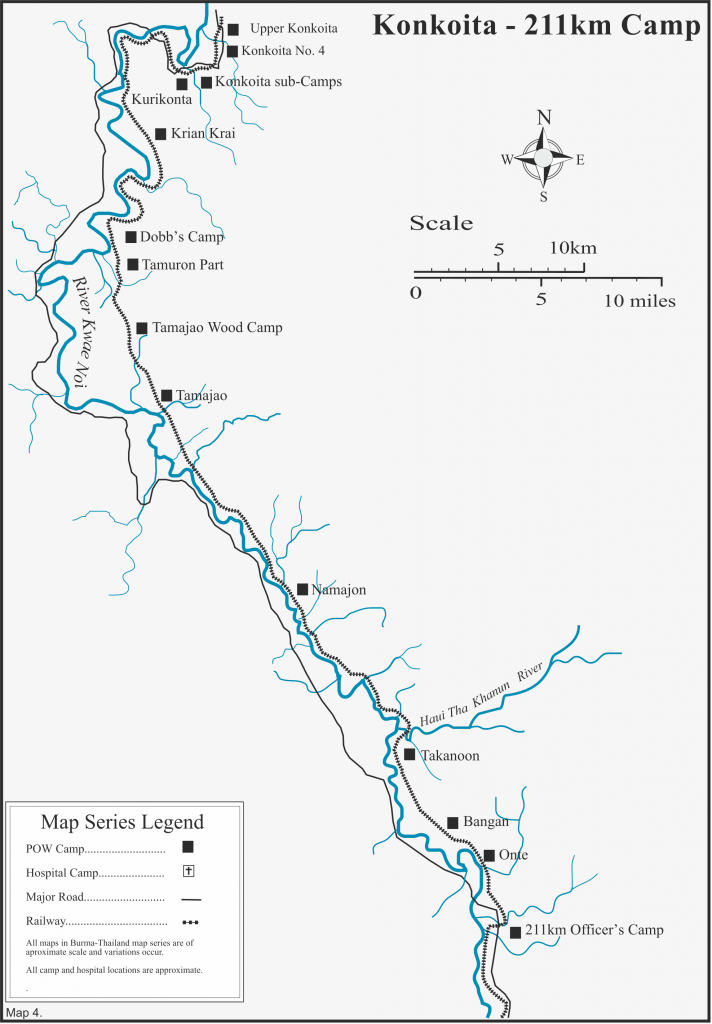

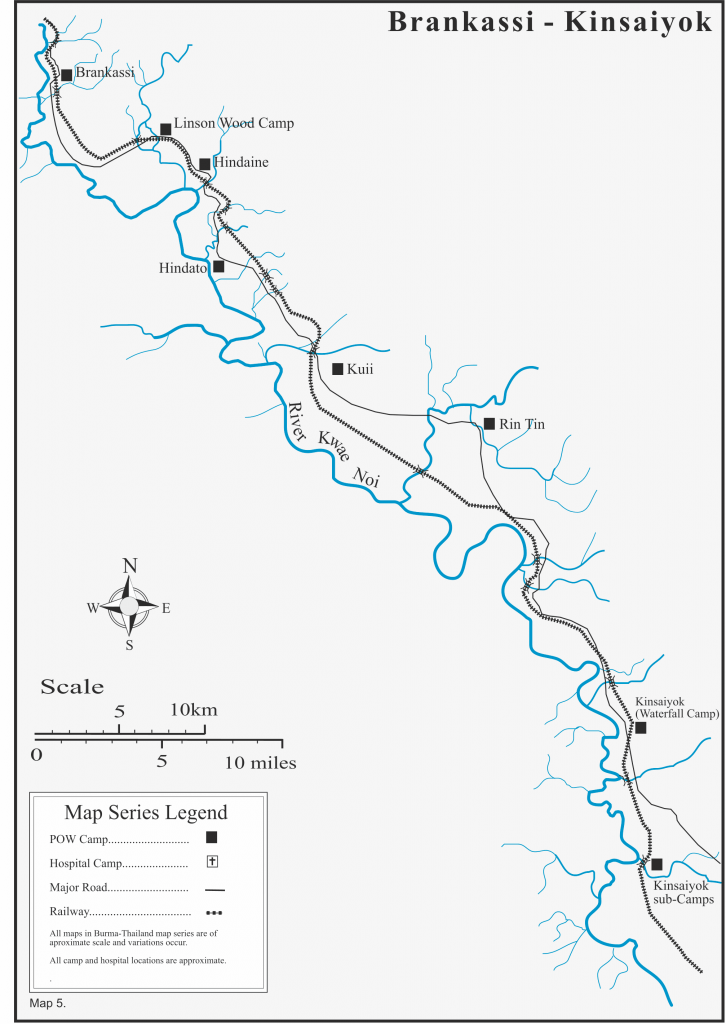

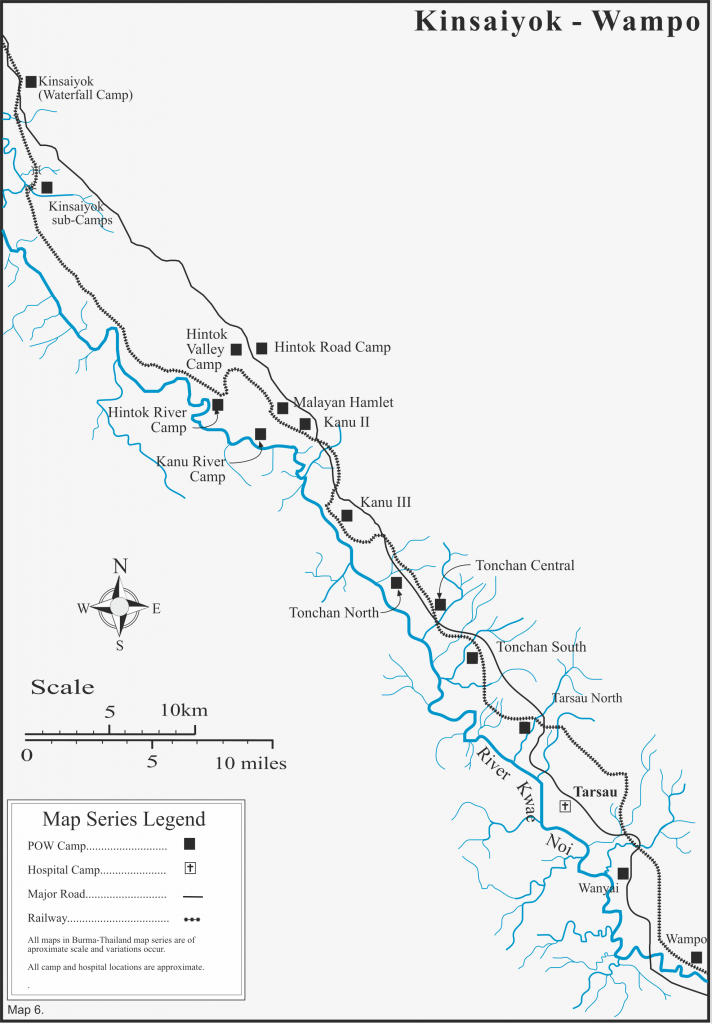

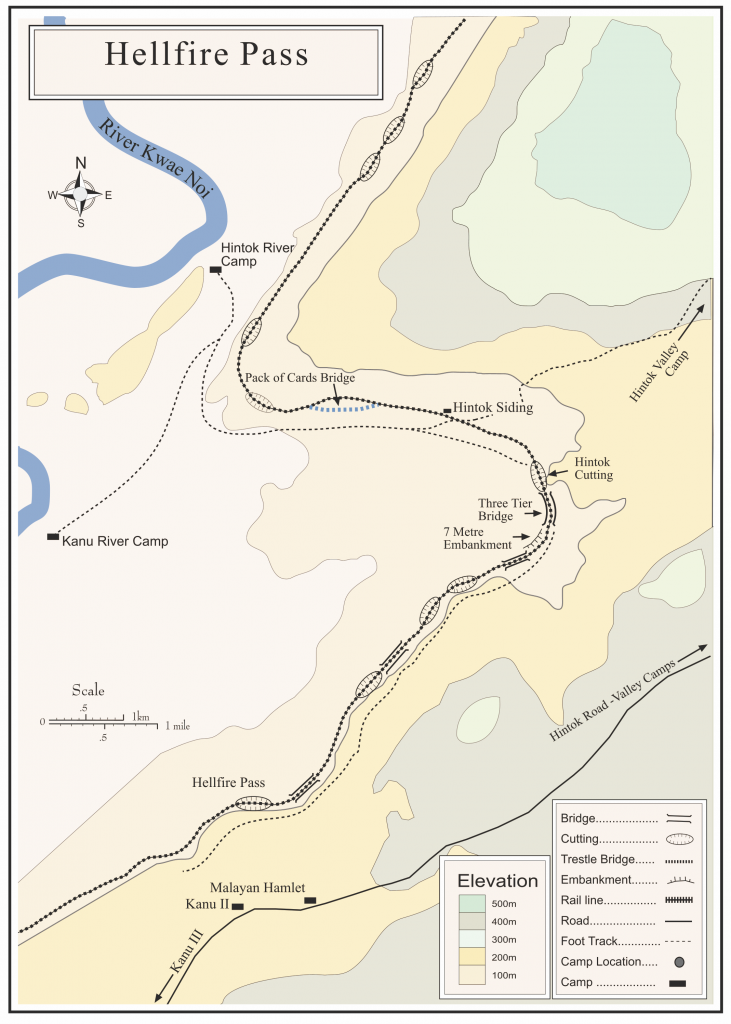

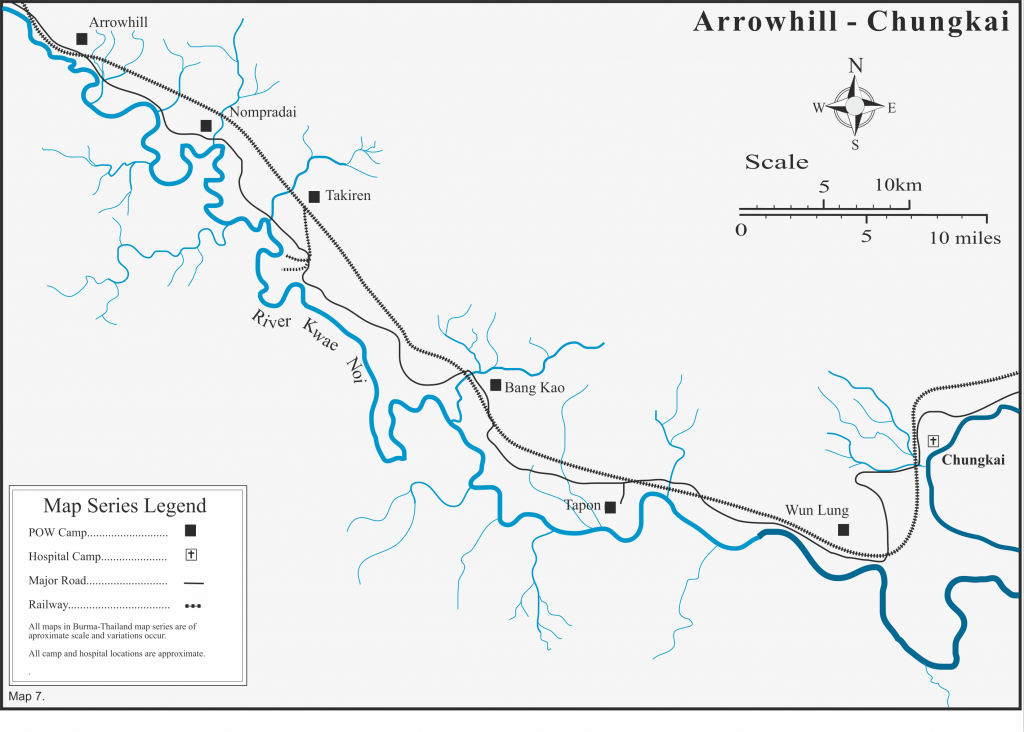

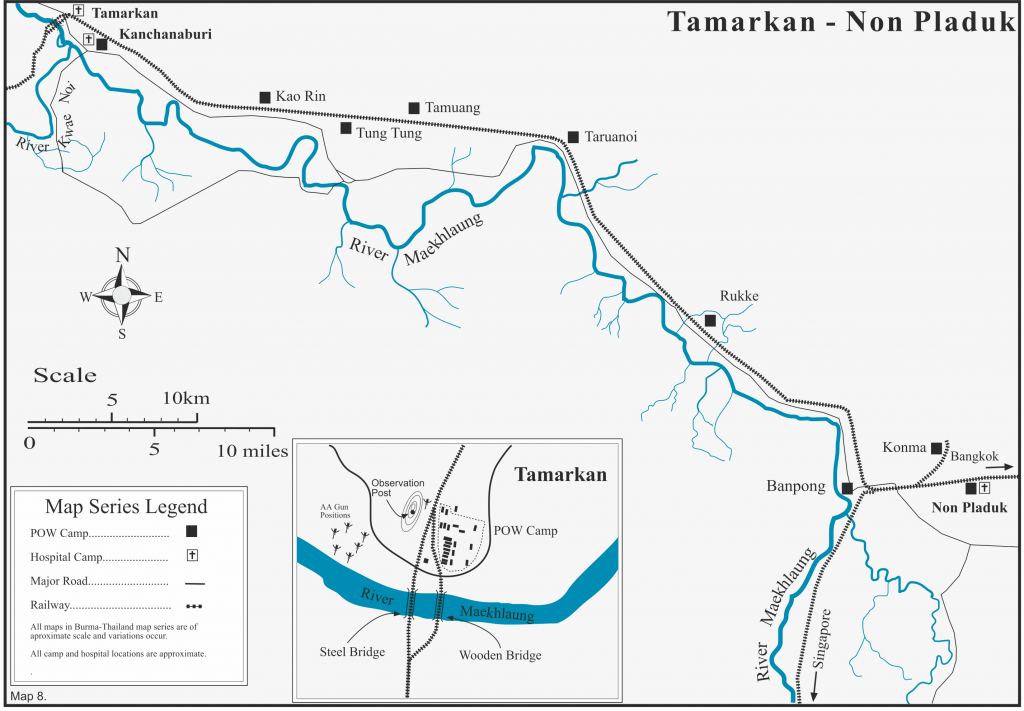

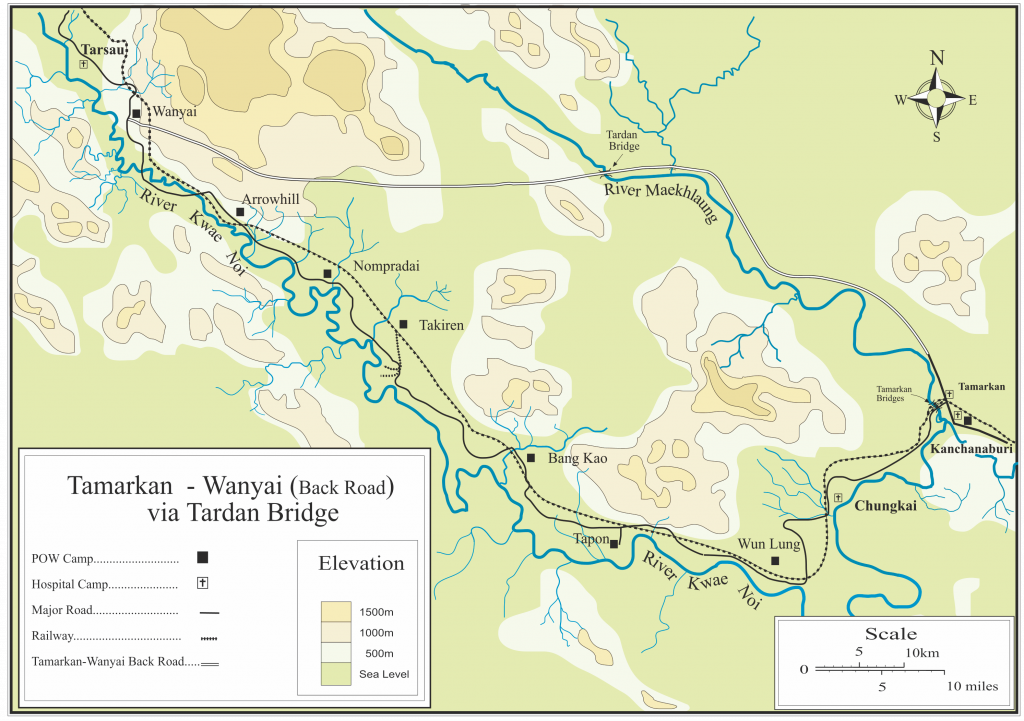

The follow series of maps published on the AUS 2/4 MG Bn site [https://2nd4thmgb.com.au/soldiers-all/camps-and-maps/ ]shows the terrain that determined the precise route the railway took (particularly maps 7 & 10):

8.1a Engineer Survey Teams

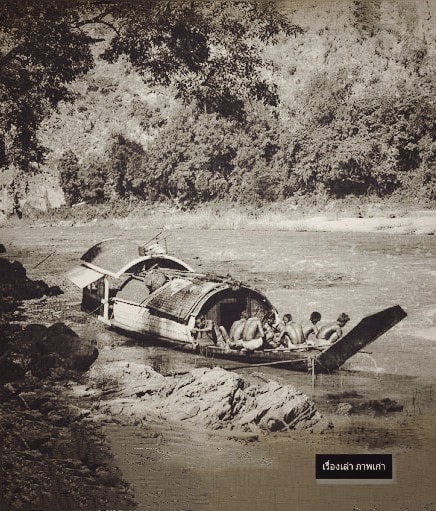

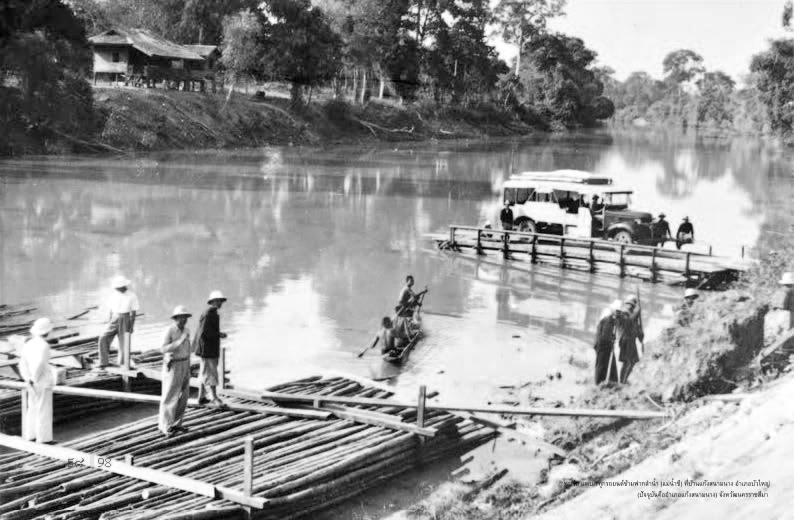

Here we have a rare photo of IJA Railway Engineers marking the path of the TBR. These survey teams were the true unsung heroes of this project if we might be allowed to credit their efforts. The decision of the general route for the Thai-Burma link was made purely on the basis of aerial surveys. It fell to these small teams of engineers to hack their way through virgin jungle to establish the exact path that the railway would take.

They would have had to subsist on the most meager of rations and supplies, mainly delivered by boat up the Kwae Noi River. But hunting and foraging must have consumed a considerable amount of their time and effort.

They would have had only the crudest of maps and aerial photos to suggest the path. They undoubtedly had to backtrack and redo sections of the survey as their path met unanticipated obstacles. Fortunately, the terrain in Thailand between Chung Kai and Nam Tok/Hintok was fairly flat and the route would have been easily mapped. They would have honed their survival skills over that 50-60 Km stretch. At Hintok, however, the task became infinitely more complex. They had to plan a route that would allow the locomotives to pull trains into the higher elevations of the route as it approached the Burmese border. Seemingly, they actually skipped this area and proceeded onto the plateau in the Sai Yok area to continue to lay out the right of way. It would fall to the bridge builders to span the gap with switchbacks and trestles as well as a handful of small cuttings to connect these upper and lower sections.

Unlike the way in which the berms and cuttings were made — simultaneously at many points – the survey had to be done linearly in a continuous line. IOW it was not possible to have multiple teams working simultaneously since it would be nearly impossible to connect up such independently surveyed sections.

These teams spent weeks alone in the jungles subsisting and surviving until a replacement team could locate and relieve them. Fortunately for those assigned to construct the berms and make the cuttings, the first 100 or so kilometers on both the Burmese and Thai Sectors were reasonably easy to survey so actual construction could proceed while the more difficult regions in the center half of the route was being slowly surveyed.

8.1b Bridges

The TBR as a whole required the construction of some 600 bridges; large and small. But only a few crossed over rivers and most of those were in Burma. The famous Bridge over the River Kwai is the only one in Thailand to cross an actual river. A few of the smaller ones cross tributaries.

In the war-era there were actually very few bridges across Kanchanaburi’s two main rivers. Because the province was dominated by these two river systems, boats were a common form of transportation; likely the most common[1] [1]. The ancient walled city of Kanchanaburi was built around a large port. It was a trading center for goods moving up and down the river. The Mae Klong was navigable (by small boats at least) along its entire length from its origins in the western mountains to the Gulf of Siam. Many of the settlements along the river have names that include the word ‘Tha’ (ท่า ) meaning port, pier or landing. The famous bridge is located at ThaMaKam (ท่า ม้า ข้าม) meaning the ‘place where horses cross’. With boats aplenty, bridges were superfluous. People, livestock and goods were simply ferried across the rivers. Even the IJA established sidings running to the river banks where goods were ferried across and reloaded onto trains to continue west. Most of the POWs who worked the next 50 Kms from ChungKai to WangPo were carried to their work camps by boat along the Kwai Noi.

Wheeled land transportation was largely by ox-cart and these could easily fit onto a ferry if necessary. It would be decades after the war, as Thailand progressed and trucks and cars became common, before bridges spanned these rivers. Access to the ChungKai war cemetery was only via boat until the 1980s. A small pier is still maintained there today to accommodate tourists who arrive by long-tailed boat.

Upstream from Kanchanaburi City there was seemingly only one bridge across the Mae Klong River. This was a wooden structure at Tadan, nearly thirty Kms beyond the Railway bridge. Even after the two bridges at ThaMaKam were complete, they were not used as pedestrian access, i.e. few POWs making the trek from BanPong crossed the river here. Most continued west towards LatYa and crossed the Tadan Bridge. Had they crossed at ThaMaKam, they would have encountered the WangPo viaduct [K113] about 50 Kms beyond. This, too, was not outfitted for pedestrians. Lt. Coast describes how precarious a walk it was as his group moved up country from the camp at ChungKai. Seemingly, only those men in the camps between ChungKai and WangPo walked across the viaduct.

That viaduct at WangPo was necessitated by a huge mountain that extended well inland from the river bank. Using the Tadan bridge meant that the trekkers went around this mountain altogether. From Tadan, they headed SW meeting the Kwai Noi and the TBR trace in the area of Tarsao [K125]. Untold thousands of POWs (most notably the 10,000 members of F&H Forces) as well as most of the romusha from Malaya followed this route to their assigned work places in the highlands of Thailand. Once reaching Tarsao, many of them had a journey of nearly 200 Kms more to reach those work places!

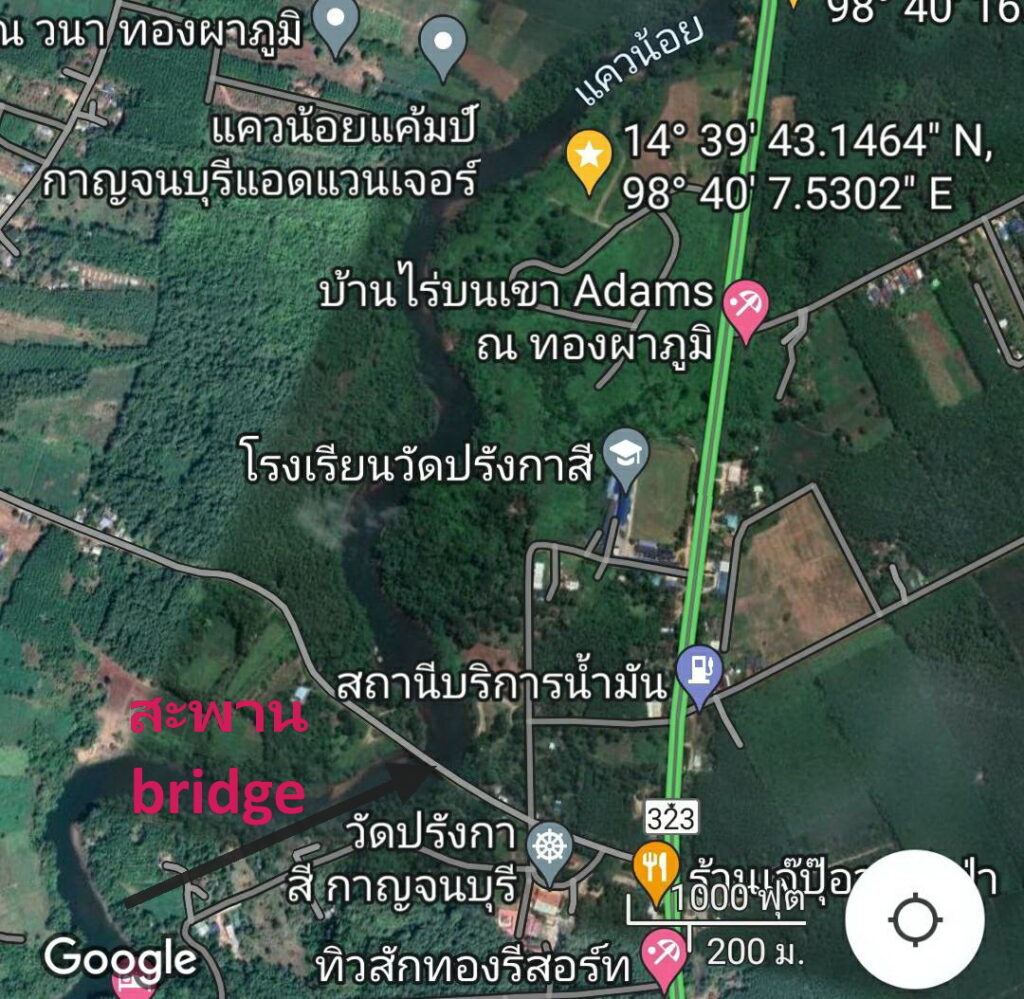

It is also worthy of note that the TBR trace never actually crosses the Kwai Noi River. It runs roughly parallel to it along the north bank. All bridges over water are over tributaries. There is only one documented pedestrian bridge that crossed the Kwai Noi. This was near Wat Prang Kasi [K210]. For reasons that seem lost to history, it was termed the Futamatsu Bridge for the lead 9th Railway engineering officer. It is not part of the TBR nor is there a clear reason why he would have had anything to do with its construction. There does not appear to be anything on the south bank of the river at that point that would have called for the building of such a bridge. In his book about the TBR, he does not even mention this bridge.

There is one more bridge of note. That is the one near SangKlaburi that in one version of the story is the model for the prop bridge built in Sri Lanka for David Lean’s movie set. While it does indeed seem to resemble the prop bridge in style, there is a competing version that says Lean instituted a completion to submit a bridge design. This was reportedly won by a team of MIT students. It is unlikely that in the early 1950s they would have had access to photos or even awareness of the SangKlaburi Bridge.

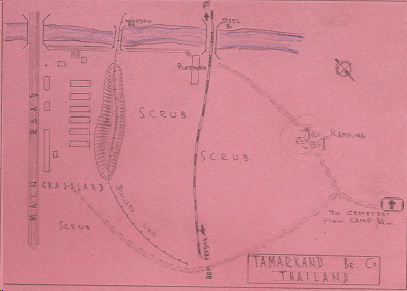

There is another side-story that involves bridges. In the immediate post-war months an Australian Lieutenant Flaws drew maps to assist the searchers to recover the remains of the POWs buried along the route of the Railway. It is quite clear that he relied on information provided to him by other POWs for those maps. IOW he did not always have direct knowledge of the places for which he drew maps. Perhaps the best example of this is that he depicts a road bridge at ThaMaKam near the two railway bridges. No such bridge ever existed! The nearest bridge some 1.5 Km downstream wasn’t built until the 1980s.

[1] Even the road that linked Kanchanaburi to BanPong was little more than an ox-cart trail. It is reported that romusha were used to both improve that road and maintain the tracks of the TBR along this 50Km stretch.

8.1b 6 Sections

It may seem somewhat ironic, but it is clear that the earlier a POW or AFL arrived the better their chance of surviving the ordeal. Perhaps this can best be explained by describing how the various portions of the TBR in Thailand differed and how that affected the health of the workers. For purposes of this discussion, the Railway in Thailand can be divided into 6 sections, each having considerably different terrain and logistical considerations.

Section 1 was built by Thai workers between SEP and NOV 1942. Although they were technically part of the romusha, their experience was so different from the imported laborers who arrived in 1943 as to put them in a category of their own. No sooner did they complete that first 50m Kms of the railway than the BanPong Incident ended the direct Thai contribution to the effort.

Section 2 runs from the Mae Klong Bridge to Tarso, about 70 Kms. The workers here were primarily British POWs. This section was completed in late APR just as the monsoon and Speedo period began. This section includes LtCol Toosey’s bridge builders who had perhaps the most benign (least horrific?) TBR experience. The next dozen or so work camps beyond the Bridge were located on flat open terrain close to the Kwae Noi River. This was the main supply route using boats and barges. The primary task for the POWs was moving dirt to provide a stable base for the tracks. This was tedious and labor intense but overall not too difficult compared to what was to come. Even building the half-kilometer long viaduct at WangPo only took a few weeks. When these men completed the railway at their camp, they were moved west to a new place of work.

It must also be remembered that the POWs who were working this area had left Singapore before conditions there had begun to deteriorate. They arrived in Thailand in quite good condition. In the short time that they labored in this area malaria and dysentery began to take their toll, but the effects of starvation and avitaminoses (Beri-beri, pellagra, etc) had yet to set in. The number of workers was still small enough and the distance back to HQ was short enough that the supply chain could still cope. This would soon change.

Beyond the WangPo viaduct and Tarso, the terrain dictated that the railway take a hard right turn inland, away from the river. Supplies became more difficult to deliver and the influx of new workers was beginning to overtax the logistics system as a whole. The TBR was now traversing dense virgin jungle.

At Km 150, a huge limestone outcropping blocked the path. This was at Konyo, later to be called HellFire Pass. This was the longest and deepest of the cuttings and the beginning of Section 4 which includes the Hintok area camps. Most of the POWs here were Australians. Kunyo is also the first place where thousands of AFL were documented to be working alongside the POWS. These men of D Force from Singapore were much less healthy upon their arrival in Thailand. Conditions on the TBR were deteriorating rapidly. This was the shortest of the sections but required some of the most arduous labor by thousands of POWs and romusha.

Beyond Hintok, the railway rose into what can be termed the highlands to distinguish it from the more or less sea level elevation of the previous 150 kms. Section 5 was the longest at over 100 Kms up to the joining point at Konkoita. The railway wound its way around hills and through valleys requiring a large number of bridges.

At Konkoita, the area of responsibility of the Thai Sector 9th Railway Regiment met that of the Burmese Sector 5th Regiment. The next 45 Kms were in Thailand but technically under the purview of the latter. But this becomes a confused area of responsibility. Most of the POWs who were sent to this area were members of F Force. By the time they departed Singapore, conditions there were grave. These men were already far from healthy upon their arrival at the BanPong transit camp. They had then been forced to walk up to 300 Kms just to get to their assigned work camp. Almost immediately upon arrival they were struck by cholera. These 7000 men actually contributed very little to the construction of the railway. They were simply trying to survive; many did not. It was the romusha and then workers who crossed over from Burma who built the railway in this Section 6.

The ANZAC Portal’s take on bridges:

A few reasonable vdos: