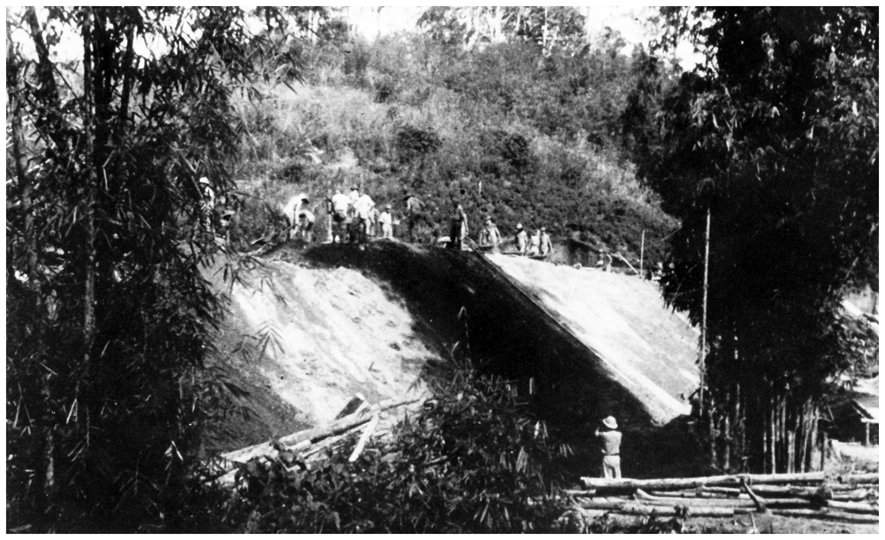

The first 50-60 kilometers in either direction of the TBR were built rather easily and quickly over flat, open terrain. Just west of the POW camp at Chung Kai, the engineers met their first real obstacle. At Khao Poon there were two limestone outcroppings blocking the path. British POWs, mainly officers, from Chung Kai chipped and chopped their way through that stone. The approach to the first cutting also required a berm about 100 meters long and 10m high. They also built a few small bridge spans adjacent to the cuttings. The small bridge between the two cuttings is often referred to as the “Officer’s Bridge”.

LtCol Cary Owtram served nearly his entire TBR period at the ChungKai camp much of that as the Allied Commander. He returned from the Kanchanaburi Officers’ Camp soon after the end of the war to retrieve a diary that he had buried there. He was amazed to discover that the camp had been razed and parts of it burned. I’d imagine that this was a final effort by the Japanese to prevent any contagion. ChungKai had been a hospital camp and also served as a quarantine camp prior to consolidation of POWs at KAN. Owtram had noted that during the cholera outbreak a large number of cases had indeed been brought there from the up-country camps and over 100 had died. So burning the buildings would seemingly make sense to the Japanese. He retrieved that diary and published it in the 1950s.

British POW John Coast recounts one of the few instances where the IJA Railway Engineer (Lt Teramuto) interacted directly with the prisoners inflicting beatings on them regularly.

Once past Khao Poon, the railway ran more or less parallel to the Kwae Noi River until it reached the next major obstacle at Wang Po and the Arrow Hill cutting.

Alternate Route #1:

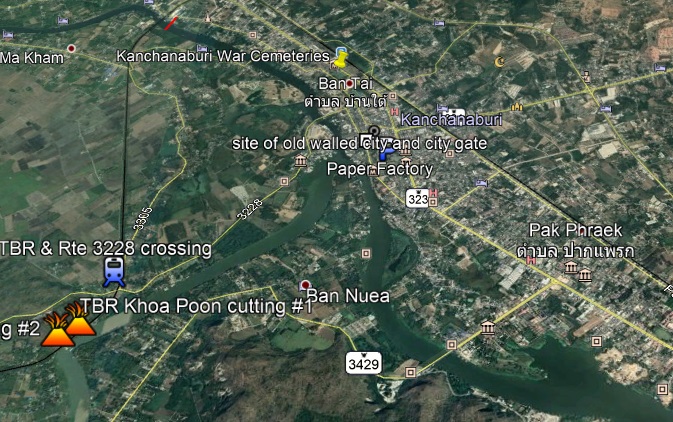

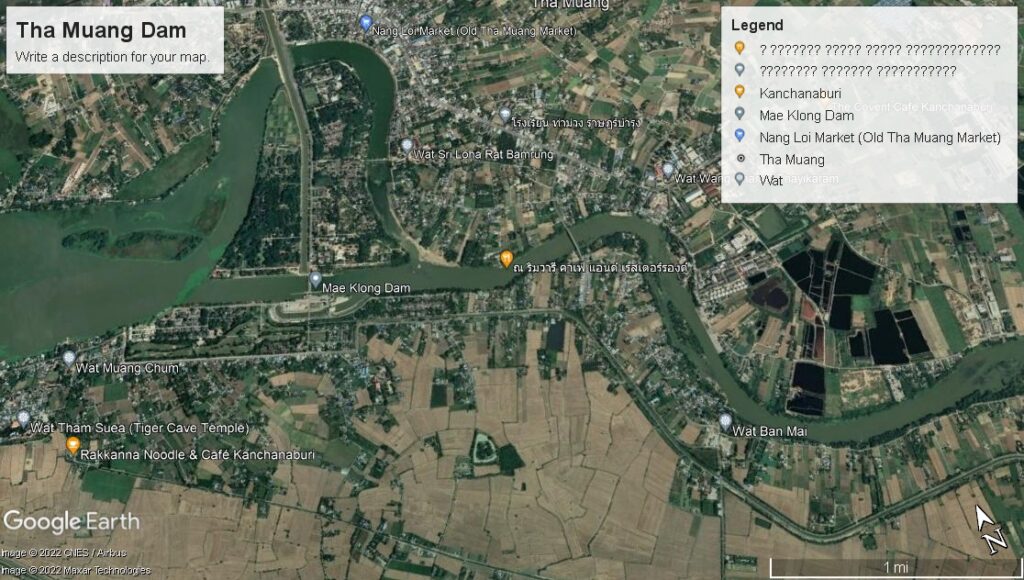

I believe that it is generally accepted that the first 50+ Kms of the TBR were built by Thai workers and that Allied POW involvement began at the ChungKai camp area. The major task of that largely British group was to hack through the two limestone barriers at Khao Poon. But I must ask if there may not have been an alternate route. In this modern day screenshot from GOOGLE EARTH, we can see that there is a road bridge across Mae Klong in the area of PakPraek. One reason IJA Engineer Futamatsu gives for routing the rails to ThaMarKam before crossing the river was the perceived instability of the river bed in the immediate area of the Walled City of Kanchanaburi. But might they have crossed to the south bank at Pak Praek? As one can see on this screenshot, there is quite a large mountain immediately to the south of Rte #3429, but there is more than enough room to have laid rails along the south river bank. That mountain could also likely have provided trees for ties and stone for ballast. After looping around the tip of that mountain (following the path of Rte 3429 in the screenshot), they then could have proceeded west — avoiding the Khoa Poon cuttings and crossed to the other side of the Kwai Noi at almost any point. With only one more crossing of the Kwai Noi, they could have rejoined the TBR near Nong Ya after a journey of about 9.5 Kms (yellow line).

In all, this alternate route would have shortened the overall length of the TBR by over 10 Kms and seemingly simplified the construction by avoiding the Khao Poon cuttings. Of course, it would also have eliminated the bridge at ThaMarKam and shifted it about 10 Km to the south.

Alternate Route #2:

Recounting events of what actually happened is one part of recording history. But as one is learning what truly occurred, it is incumbent to ask why it happened in this precise way and not some other. I address some alternatives in Section 25.0.

We know from Chief Engineer Futamatsu’s account why the existing bridge was constructed in that location. But it is also one of the longest spans along the route. There could have been no doubt in the planner’s minds that such a formidable structure would catch the eye of the photographic intelligence analysts. But would it have been possible to have crossed the river that blocked their path in a less obvious way? I bring to your attention the current dam at Tha Muang = about 16 Kms before the bridge at ThaMarKam. In point of fact there are two bridges shown. One crossing the dam itself and another road bridge a short distance downstream.

I am certainly no engineer, much less have any true knowledge of bridge building. We must also remember that the Railway Engineers were using the old British aerial survey maps to plan their basic route. I will also grant that modern building techniques have allowed for the construction of things that no one would have dreamed of in the 1940s. But if I were viewing aerial photos for the first time, I’d be looking for the shortest route and the shortest way across that obstacle. I will also grant that modern engineers have no qualms about moving thousands of tons of earth to build things like a simple overpass to ease traffic. [see Section 11.6 for thoughts on the dam’s construction]

I have driven across that dam and in the area surrounding it many times. To my uneducated eye, there is little evidence of a massive movement of earth to allow for that dam to be placed where it is. IOW there is no significant earthen dam as part of the iron gated structure. I suppose that anything is possible and that this evidence is just disguised by landscaping, but I doubt it. My conclusion is that this is one of the narrowest sections of the river. Bernoulli’s Law teaches us that with fluids narrowness leads to an increased rate of flow. So perhaps the threat of a huge increase in flow rate during the monsoon season was reason enough to reject this point as an ‘easier’ crossing point.

One of the most basic elements of bridge building is a stable surface on which to place the pilings. According to Futamatsu, this is what finally determined the placement of the bridges at ThaMarKam. It is entirely possible, although not documented, that engineers prospected many different sites before making their final choice. My intention is to simply point out that there were very likely a number of alternative crossing points short of the one chosen. I would also note that downstream from the dam the river channel is in a much deeper cut than the area upstream. Any bridges downstream would have been higher but much shorter in span. Had it figured into their decision making, a short span would have been much smaller a target for the bombs that inevitably would be aimed at it?