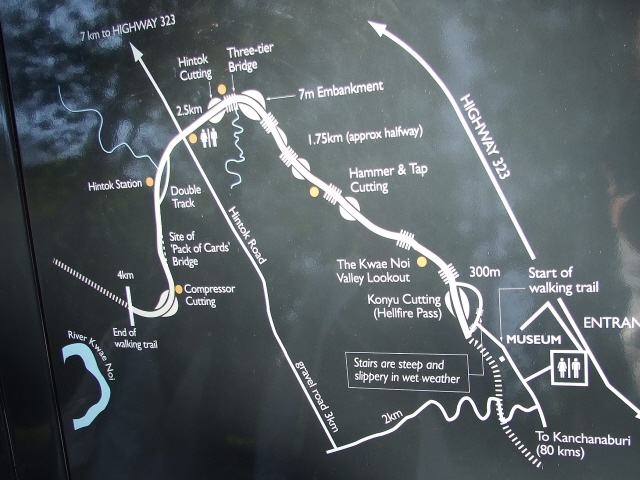

Perhaps the most infamous portion of the TBR is found near the 150 Km point as measured from Nong Pladuk. It is known as HELLFIRE PASS. The name originates from the torches used while the POW and romusha laborers were forced to work round the clock to complete this, the longest cutting on the TBR route. More treacherous terrain lay ahead as the railway rose into the highlands as it neared the border, but this area is known for the horrendous conditions the POWs had to endure. Just beyond the cutting are two of the larger trestles called the three-tiered bridge and the Pack of Cards trestle — the latter because it collapsed at least twice during its construction. No photographs of the Pack of Cards trestle are known to exist and the Three-tiered bridge was dismantled post-war. So only period photos of it survive today. The task of making this cut was assigned to the members of D Force [composed of 2800 British & 2200 Australian POWs] to which were added some from H Force. It is reported that 69 men were beaten to death during the 12 weeks it took to complete this task. During its construction the members of H Force living at the Malay Hamlet and Hintok Valley camps were also battling an outbreak of cholera.

The Australian government maintains a memorial museum on the hillside overlooking the Pass as it has been reclaimed for trekking. Venturing much beyond the actual cutting is for the most fit and adventurous tourists only.

The ashes of LtCol. (Dr.) Sir E.E. “Weary” Dunlop who commanded a camp nearby were scattered here.

===============

Work began on HellFire Pass on 25 APR 43 (ANZAC Day) initially by D Force then later augmented by men from H Force.

It is generally reported that dozens of these workers were beaten to death during the 9 weeks of construction.

HOWEVER, CWGC records do not reflect these numbers. In fact, only a single POW is recorded as having been beaten to death in this area in this time frame. No men are even recorded as having died of an injury! Nor are there any significant numbers of deaths for which no cause is noted.

I suppose that many of these beating deaths COULD HAVE been among the romusha that also worked this project. But that is not the way that POW survivors narrate it.

Construction of the cutting commenced on 25 April 1943. The excavation of soil and rock was carried out using 8 lb hammers, steel tap drills, explosives, pinch bars, picks, shovels and chunkels (a wide hoe). For a short time an air compressor and jack hammers were used. The bulk of the waste rock was removed by hand, using cane baskets and rice sacks slung on two poles. In an attempt to complete the section on schedule, for the six weeks leading up to its completion in mid-August, prisoners were forced to work 12 to 18 hour shifts around the clock, without a rest day. The Hellfire Pass section of the Burma–Thailand Railway cost the lives of at least 700 Allied POWs, including 69 beaten to death by Japanese engineers or Korean guards.

As per the caption above: “The Hellfire Pass section of the Burma–Thailand Railway cost the lives of at least 700 Allied POWs, including 69 beaten to death by Japanese engineers or Korean guards.” I have no reason to doubt or refute these figures except that the official records of the War cemetery at Don Rak do not record any deaths of this magnitude.

Nearby NamTok and Sai Yok:

A photo essay by Richard Barton (with permission of the author):

Below is a photo of the view of the Kwai Noi River taken in the Hintok/ Hellfire area. It is from a viewing point along the HellFire Pass trail. It is one of the more scenic points and it appears in many videos and presentations but is rarely identified.

Perpetuating fiction:

In the 1990s, a small group of Americans from Bangkok became concerned that the participation of American POWs in the Thai-Burma Railway was in danger of being lost to history. These men labored and lobbied for years to get permission from the Thai authorities to erect a monument to those POWs. It is not recorded as to whether or not they were aware that that memorial was placed only a short distance from the compound where those Americans had been housed in the ‘rest camp’ at Kanchanaburi. Nor were they likely aware that this would be one of the few items linked directly to that period of history that the Thais would just as soon forget.

Over the ensuing decades, we have learned that the number of deceased US POWs mentioned on the plaque is incorrect. But that is no reflection on the men who designed it. Although its exact origin is lost to history, the number 356 was the accepted data for the time. Although slightly incorrect this plaque was erected in good faith and was in concert with the known information at the time.

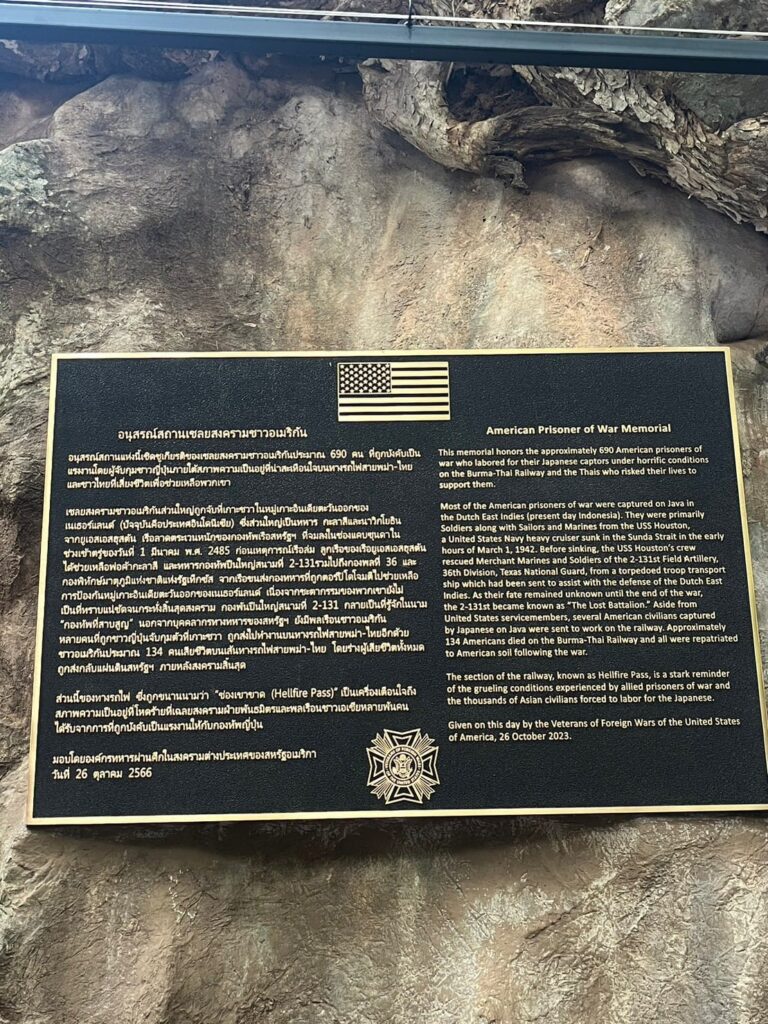

In OCT 2023, another plaque sponsored by the US VFW organization was hung at HellFire Pass. Like the novel that gave the Bridge on the River Kwai international fame, this new plaque contains a fictional account of the story of the US POWs. It is a blemish on the memory of the 133 Americans who died and the nearly 1000 who were directly or indirectly associated with this event for this plaque to remain on public display relating a fanciful account of their journey through a special kind of hell.

Just to relieve any notions by the choice of venue, there is no record that any US POWs labored alongside the Australian and British POWs there. But HellFire Pass is the first location where there is photographic evidence of the tens of thousands of Asian Forced Laborers who worked alongside Allied POWs. The main reasons why the US participation is easily overlooked is that the vast majority of them labored primarily in Burma and the remains of the deceased were repatriated to their families in the US rather than being interred in the war cemeteries in Thailand or Burma.