The decision to use POW labor to build the TBR was actually made late in the planning stages. The British were the first to explore the concept of connecting Thailand and Burma — and in doing so forming a rail network that linked to Singapore and even Phnom Penh. They had mapped portions of two possible routes. One ran west from central Thailand starting at Pitsanulok, but the mountains along the border were a formidable obstacle.

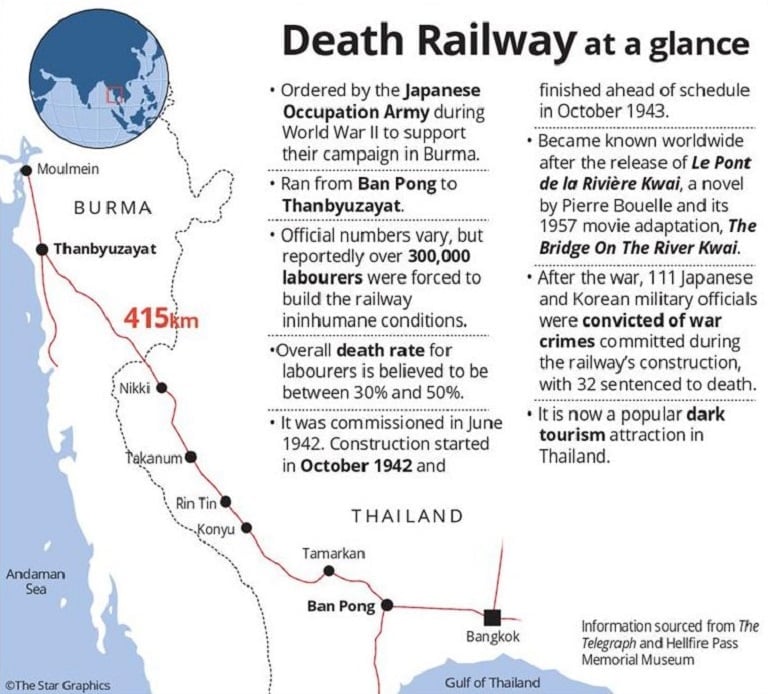

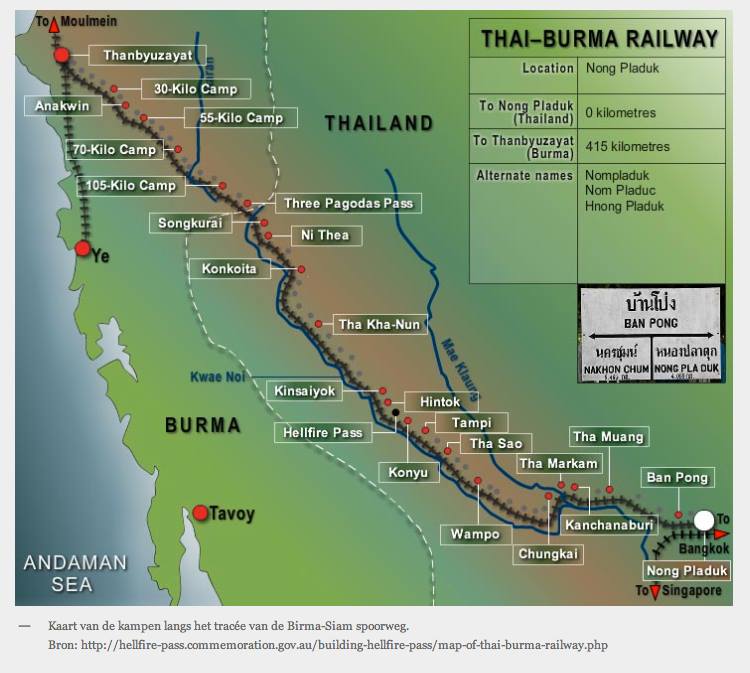

The somewhat easier route that the Japanese finally adopted ran along the path of the Kwae Noi river from Kanchanaburi to the border crossing at Three Pagoda Pass. In Burma, it traversed a series of mountain ranges and crossed rivers in the valleys between them before flattening out as it approached within 50 Kms of Thanbyuzyat.

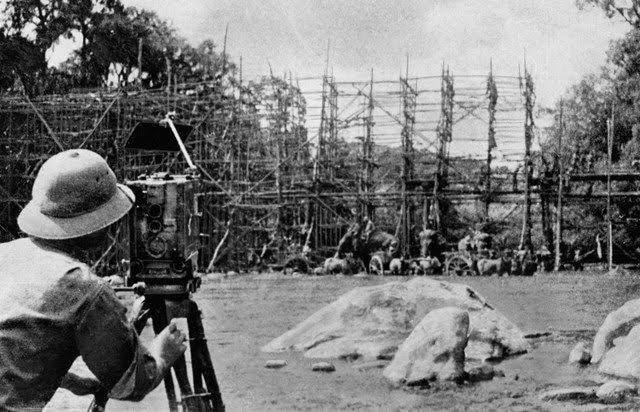

All of this area had been aerial mapped but it fell to a small group of intrepid Railway Engineer survey teams to walk and map the entire route.

The original concept was to hire tens of thousands of indigenous laborers, but in FEB-MAR 1942 the IJA suddenly found itself in possession of well over 150,000 Allied POWs mainly in Singapore and the Dutch East Indies. The majority of the US POWs were taken as POWs on the island of Java. They and their fellow Dutch and Australian POWs were then trans-shipped to Burma to work the TBR.

I have yet to see it formally written or even speculated upon, but it does seem that just as the two sectors of the Railway were assigned to the 5th and 9th IJA Railway Regiments, the provision of workers was divided as well. For the most part (if not exclusively) the POWs who worked the Burma Sector originated in Java. It was incumbent upon Singapore to supply the workers to the 9th Regiment. The most prominent exception to this division was the work group that was commanded by LtCol Dunlop.

From the Mansell website:

http://www.mansell.com/pow_resources/camplists/death_rr/movements_1.html

Dunlop Force: Under the command of Lt Col Edward Dunlop a noted Australian surgeon, 895 made up of 15 Officers 12 WOs and 868 ORs left Bandoeng, they were joined before boarding the ship by other prisoners, Australian mainly with 159 Dutch, departed from Batavia, in January 1943 first by Hellship Usa Maru to Singapore then by rail to Non Pluduc. They were the first Australians to arrive in Thailand; they were transported by trucks to Konyu and later to Hintock where they remained for the duration of the construction, working on a particular difficult section involving cuttings and embankments. In February Dunlop commanded a force of 1873 prisoners including 623 Dutch. Cholera also took a huge toll of this force with 66 deaths.

In a similar manner, the vast majority of the romusha were ‘recruited’ in Malaya and Singapore arrived by train and worked the Thai Sector. The 5th Railway Regiment ‘recruited’ exclusively native Burmese and other local hilltribesmen. The relatively small (as yet undefined) number of Thais who laid the first 50 Kms of track from NongPlaDuk to Kanchanaburi from Sep-Nov 42 worked under conditions vastly superior conditions that the Asian Laborers who followed them.

Responsibility for the surveying, design and construction of the entire system fell to two Railway Regiments: the 5th working in the Burma Sector and the 9th in Thailand. In reality, however, the joining point was at Konkoita in Thailand. So the Burma Sector was 152 Km in length and extended about 44 Km beyond Three Pagodas Pass (at Km 108) into Thailand. That leaves the Thai Sector at 263 KM at Konkoita.

This might sound a bit crass when one considers the ordeal of the slave laborers, but I think that the unsung heroes of the TBR were the small survey teams that were sent into the raw jungle to literally map and mark each meter of the railway. There were no roads, no bridges, no way around the limestone out-croppings that were to be ‘cut through’.

These small teams of 5 -10 men spent months in the jungles living off the land; trekking out each day to map and record the route that the rails would take. We know almost nothing of them except a mention by Railway Engineer Futamatsu who visited one such group early in their effort.

Another little known aspect of the construction is that the IJA Engineers relied heavily on a US ARMY Field Engineering manual (aka Merriman’s Manual) for the design and construction of many of the wooden trestles and bridges.

The logistics of the TBR are mind-boggling. IJA Engineers calculated that its construction involved building a total of 688 bridges for a combined distance of 14 Kms. These consumed 60,000 cubic feet of timber. 7 million cubic meters of rock (cuttings) and earth (filling) were moved. 300 tons of explosives were also consumed. The logged timber was moved by 400 elephants. 700 boats and barges plied the Kwae Noi river ferrying supplies.

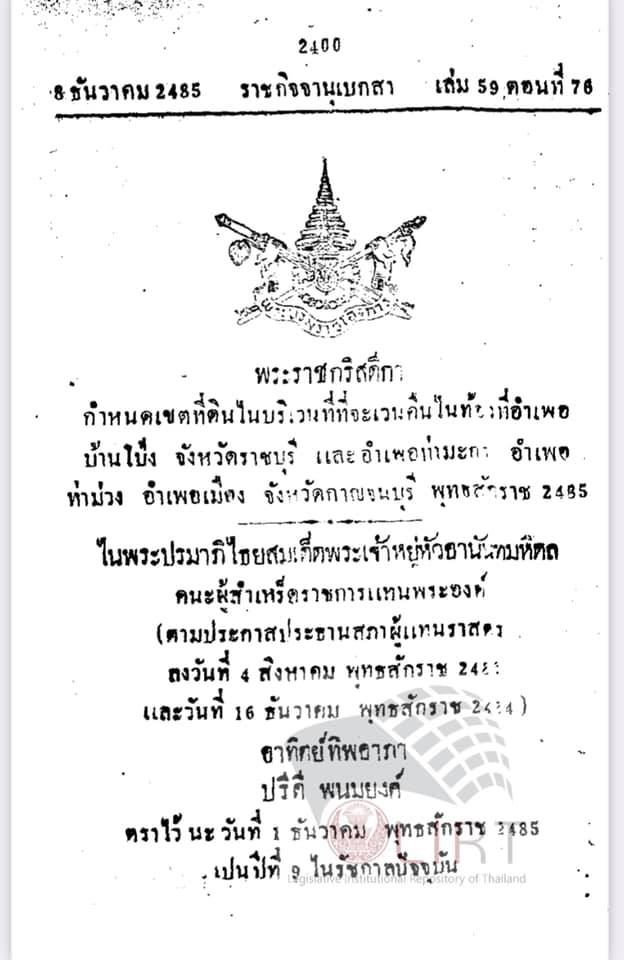

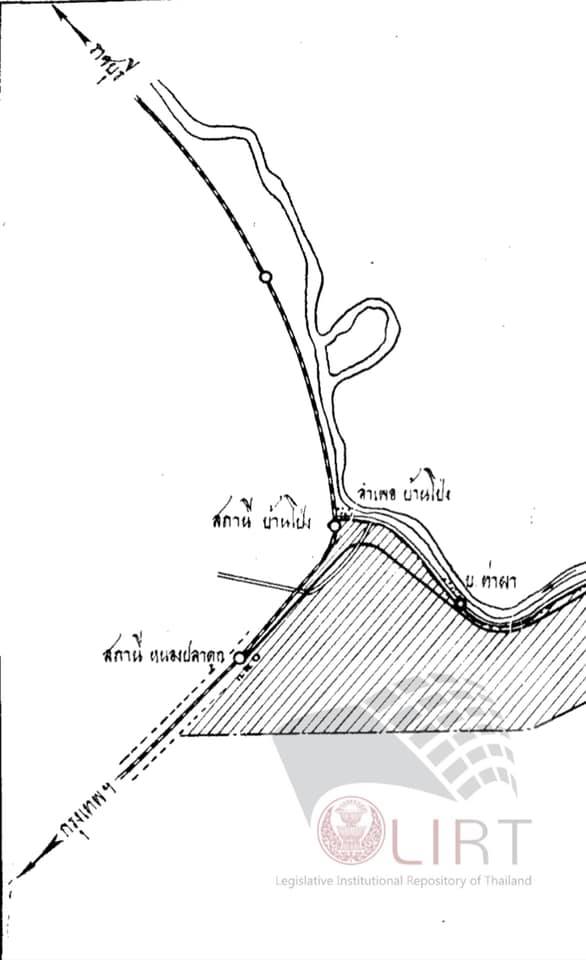

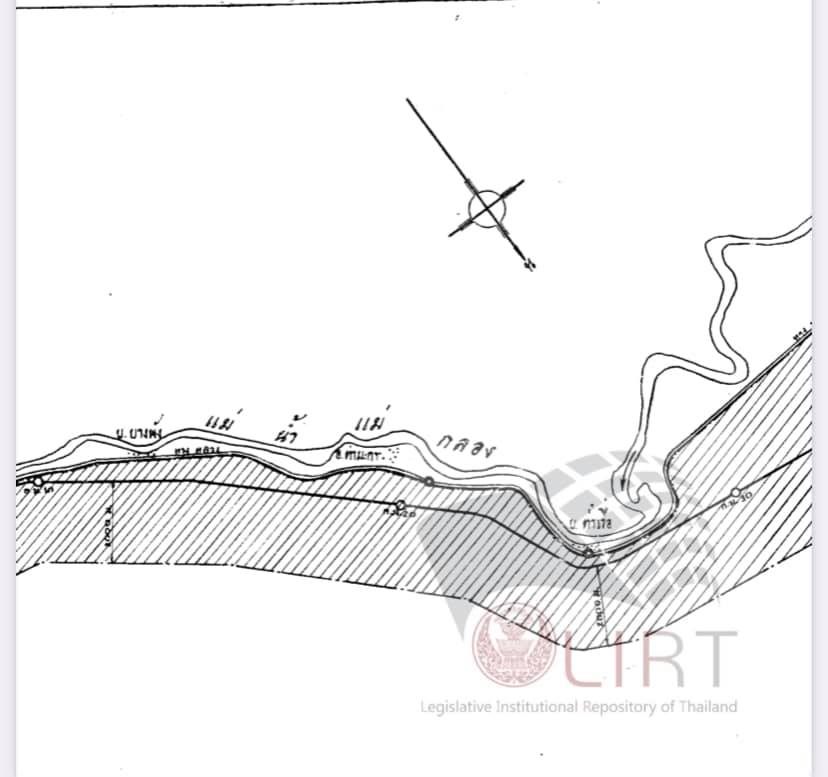

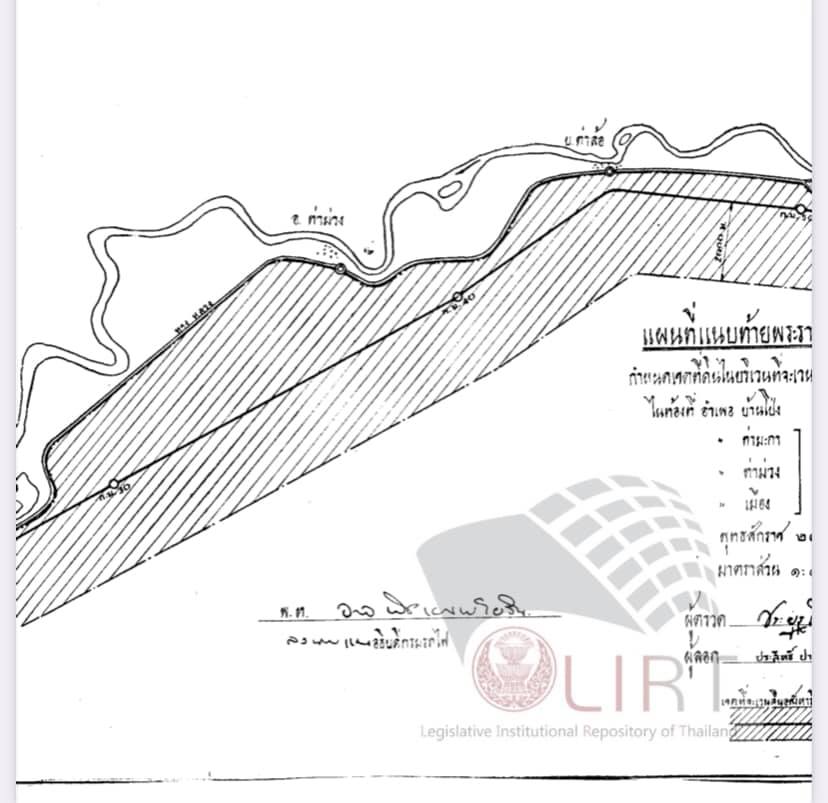

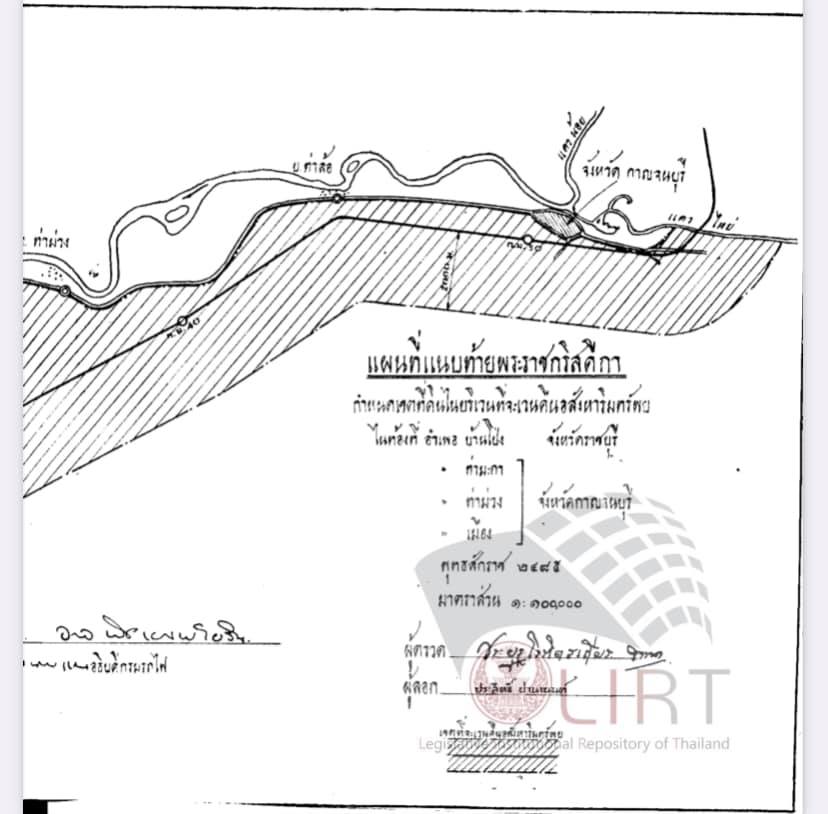

These are reportedly the documents in which the Thai gov’t transferred the usage of the land — a right of way of sorts — for the IJA to build the TBR from BanPong to Kanchanaburi:

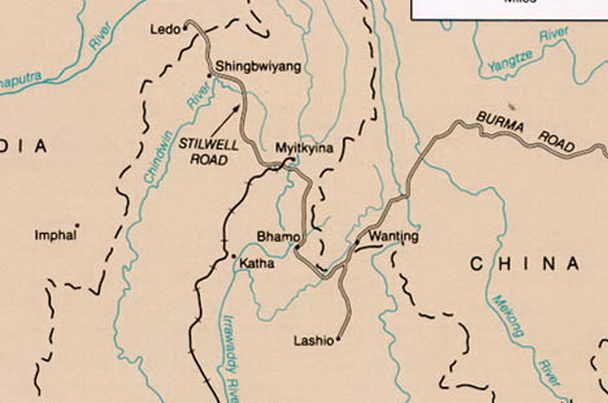

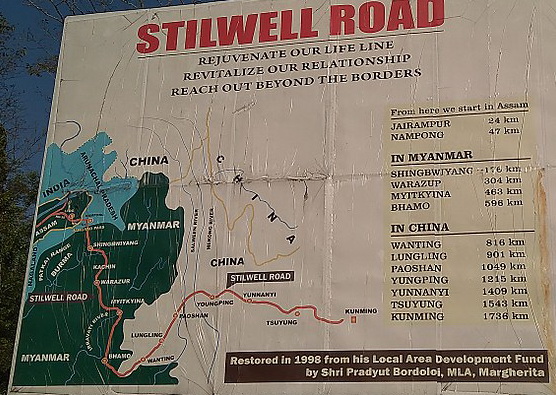

Part 2: the Stilwell-Burma Road to China

It is of historical significance that at roughly the same time, a road was being built over 1,726 kilometers (1,072 miles) to link to the Burma Road that had been cut by the Japanese invasion:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ledo_Road

http://cbi-theater.com/ledoroad/Ledo_Main.html

Based on a 19th Century British survey, it was constructed largely by Afro-American Engineer troops.

Part 3: the Japanese perspective

Here is a brief account of the concept and construction of the TBR as written in 1953.

Construction of the Burma-Thailand Railway —

Difficult Project Abandoned by GREAT BRITAIN

[as written by Takoshiro Hattori]

In early November of 1942, an important plan was formulated and its execution commenced. In other words, it was the epoch-making construction of the Burma-Thailand Railway. The supply to BURMA was mainly conducted by long sea transportation. In regard to the land supply route, there was only a poor mountain road which was constructed by the Fifteenth Army when it had advanced from THAILAND to BURMA in February 1942. It was highly possible that the sea transportation would be subjected to enemy submarine attack while over the road a maximum of 10 to 15 tons of supplies could be sent daily. To make matters worse, the strength in BURMA increased to more than four divisions in June 1942, and it was natural to estimate a further increase in strength with the increase in possibility of counter-offensive by the Allied Forces. It was anticipated that transportation to BURMA would become very critical.

Such being the situation, the plan to lay the Burma-Thailand Railway was discussed since June 1942, and the preparations commenced between the Southern Army and the Imperial General Headquarters.

Originally, GREAT BRITAIN had planned this railway construction but abandoned the project because of the extreme difficulty. This was a very difficult project.

An outline of the Burma-Thailand Railway construction plan, which was formulated in accordance with the preparation order given by the Imperial General Headquarters in June 1942, was as follows:

1. Course: 400 kilometers extending from NONGPLADUK TH to THANBYUZAYAT in BURMA through the KWAE NOI Valley.

2. Transportation capacity: Approximately 3,000 tons a day (one way).

3. Construction period: To be completed by the end of 1943.

4. Strength to be used in construction: The force with one railway inspectorate, two railway regiments and one railway stores depot as nucleus.

5. Necessary labor: Indigenous laborers and prisoners of war to be used.

In autumn of 1942, the activities of enemy submarines in the Indian Ocean Area and enemy air attacks on ports and harbors in BURMA intensified. Furthermore, there was an indication of counterattack by the Allied Forces upon BURMA, and the increase in our strength in that area became urgent. The situation being such, the construction of the Burma-Thailand Railway became increasingly necessary. Although the Imperial General Headquarters foresaw serious difficulties in this construction it decided upon the construction and issued the order in late November.

Second Inspector General MAJ Gen SHIMODA NOBUE, who was under the assigned command of the Southern Army Commander in Chief, took charge of this construction.

The construction was finally started in earnest in January 1942. At that time the war situation in BURMA became aggravated, and it was absolutely necessary to complete the construction of this railway by the end of the monsoon season of 1943.

The Imperial General Headquarters ordered the Southern Army to reduce the construction period by four months and complete It by the end of August. On 24 February, the activation of the Southern Army Railway Unit was ordered to expedite the construction. This unit was organized with the units which were formerly engaged in the construction and consisted of the 2d Railway Inspectorate, the 5th and the 9th Railway Regiments as the nucleus.

Maj Gen SHIMODA was killed la an air mishap in late January and Maj Gen TAKASAKI succeeded him.

This construction work was smoothly conducted until about April. In the middle of April, however, the monsoon season set in one month earlier than usual. This was a fatal blow to the construction. Supply was disrupted because the roads and bridges were destroyed by floods. As a result, some units were compelled to discontinue the work temporarily and conduct withdrawal.

To make matters worse, as a result of malnutrition many cases of dysentery and malaria broke out among the engineering personnel. Under such a situation, an epidemic of cholera suddenly broke out and more than 4000 personas died. Consequently, the laborers were panic-stricken and there were many eases of desertion.

The Imperial General Headquarters was aware of this fact and in the middle July it ordered the construction period to be extended two months.

The enemy air attack upon BURMA was suddenly intensified. More than 2,000 enemy aircraft raided BURMA during April 1943. In the first half of 1943, it was possible to conduct uninterrupted railway transportation in BURMA only 10 days during a month and the amount of goods transported decreased to one-third that of the preceding year. The strengthening of the defense of the Burma Area was just started, but in view of the extremely poor supply transportation, considerable difficulties were anticipated.

Along with the railway construction, the construction of three roads across the mountains along the Burma-Thailand border was expedited with a view to open them by the end of 1943.

Listed from the north, these roads were from LAMPHUM and KENG TAUNG to TAKAW, CHIANG MAI to TOUNGOO, and RAHAENG to MAE SOT.

Part 4: The progression of the construction of the TBR

It is quite clear that as work on the TBR proceeded it went through different phases. The picture becomes clearer as we trace the trail of bodies that were left behind. These are the ghostly footprints of the path these men carved.

The early phase of work during 1942 was comparatively easy and resulted in very few deaths. On the Thai side, the POWs did not become directly involved in the Railway until NOV-DEC 42. Those POWs who arrived prior to that time were employed mainly at the Nong PlaDuk railyard. They enlarged it and shifted supplies that would later be sent north. Once the first 50 Km of track was laid by the contracted Thai workers (SEP-NOV), the HQ and logistical support for the TBR moved from Ban Pong to Kanchanaburi. Soon thereafter LtCol Toosey’s work group left Nong PlaDuk to begin work on the bridges. At about that same time a group of about 800 British officers arrived at ChungKai. Many of them had been attached to Indian Army units [1]. This was the first true POW work camp tasked with laying tracks. POWs continued to arrive from Singapore and they were transported to Kanchanaburi and moved across the river on barges to the places of work farther along the TBR.

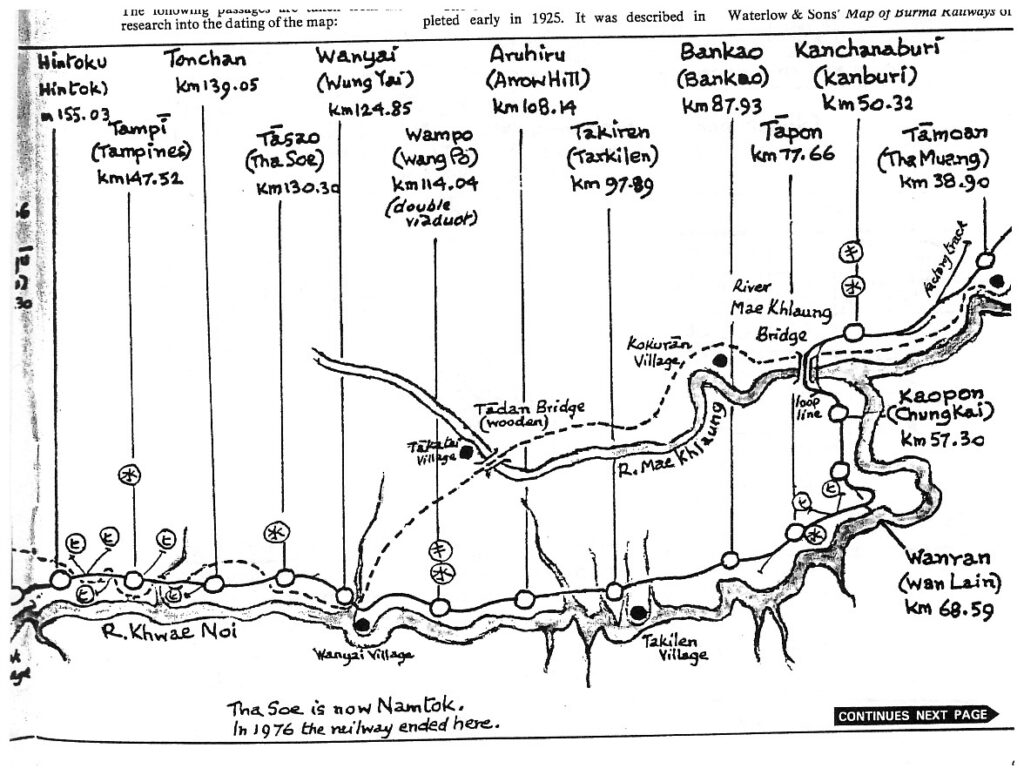

The above map also shows an alternate over-land route that many of the workers followed using the Tadan bridge [2] to cross the MaeKlong (later the Kwae Yai) river. This route allowed them to move upstream of the bridges at ThaMaKam and the Wang Po trestle before they were completed. One of the POW accounts mentions approaching LatYa (not far beyond Tadan) and I was always confused as to how that route was possible until I found this map.

But even into early 1943, the overall conditions along the route were not too bad. The workforce was still comparatively small; they were working on flat open terrain close to the river. Supplies could flow relatively easily along the river. The monsoon rains had yet to sweep it.

Overall conditions began to change just past the Wang Po trestle (K113), about 50Km beyond Kanchanaburi. Next came HellFire Pass at about Kilo 150. The terrain between these two camps was a bit more rugged. The camps in that area Tarso, Tonchan and Kanyu would soon gain a dreadful reputation. The workforce had increased to the point that the logistics operation was beginning to fail. More mouths to feed and less to feed them with. The only food item that was consistently delivered to these camps was a low-quality rice that had been stored under questionable conditions. Its caloric content was wholly insufficient for the POWs. The lack calories and other essential vitamins in their diet led to Beri-Beri and Pellagra and resulted in serious debility and inability to work.

It is also worthy of note that beyond Wang Po there were no Thai towns of any size — perhaps a few family farms — until Tha KaNun where there was a town at the wolfram mine. Here a different engineering challenge presented itself. Not unlike the limestone cliff at Wang Po, a large stone outcropping blocked the way. The solution here was to chop out an L-shaped shelf on which to place the rails. There are three camps in this area attesting to the huge amount of effort by a large number of POWs.

Beyond HellFire, the terrain changed dramatically. Beginning with the Hintok area, the elevation was changing. The highest point is at Three Pagodas Pass at 300m (1000 feet) above sea level. For a short period the Engineers left a gap here and moved workers (now more and more romusha as well as POWs) on to the plateau that slowly rises to the border Pass. The Kin SaiYok and Nikki camps were in this area. Closer to the border were the Changaraya and Song KuRai camps. The process of laying tracks in this area was not essentially different than in the ‘lower’ camps. But this portion of the route was separated from the river. The task of delivering supplies became infinitely more complicated. The entire project was in danger of failing.

Despite thousands of workers – both POW and romusha – in these highlands camps, work was proceeding very slowly. It was becoming increasingly difficult to assemble enough fit men to do the work. The Engineers worried about their commitment to complete the TBR in a year’s time frame. They put in a call to Singapore to send 10,000 more POWs and as many romusha as possible. They were looking to save their reputations. The problem was that there weren’t 10,000 fit men left in Singapore. They had been sending thousands on a Hellships to Japan; not all were arriving. Conditions in Singapore by JAN-FEB 43 had also deteriorated badly. Malaria and dysentery were wide spread; food was increasingly scarce. Despite having no ‘work’ to perform these men were still quite debilitated. The men of F & H Forces that arrived at Ban Pong in APR-MAY 43 were nothing like those who had arrived months earlier and who had built the TBR up to HellFire Pass. The 5000-man D Force had arrived in MAR 43 and was assigned the formidable task of carving their way through that limestone outcropping. Within weeks, they were joined by some members of H Force. That group had been located in the Hintok area and were primarily responsible for building the two switch-back trestles that were needed to lessen the grade of the track as it rose into the highlands. At this same time, the 7000-men of F Force were struggling to make the 200 Km trek from Ban Pong to their assigned camps nearer the border. Thousands more mouths, greater distances, more remote locations, monsoon rains, all added up to a recipe for disaster! Then cholera hit! It began in the romusha camps[3] and quickly infiltrated the camps near the border. Romusha camps were decimated. Dozens of weakened F Force men were infected; many died. This, of course, was layered on top of all the other maladies that were afflicting POWs everywhere along the TBR.

The three camps just inside the Thai border were the worst affected. But the cholera leaked as far east as the Hintok area and especially the Malay Hamlet camp (K153) where parts of H Force were housed while working the HellFire Pass. The situation quickly became dire in a number of ways. Despite the large increase in workers, it was becoming increasingly difficult to assemble a sufficient number of men to perform the necessary work. The hospital camp at Tarso was overflowing; as was ChungKai much farther back along the route. Cholera victims were flooding the meager facilities in the highlands camps overwhelming the medical staffs. And the rain continued. Things were so dire that the Engineers agree to evacuate men from the camps nearest the border; the ones struggling to contain the cholera, but the only place to take them was into Burma. A hospital camp was established at Thambaya (K50 / 365 as measured from the Thai side). Over 1700 men were sent there to drain them away from those camps. For obvious reasons, the cholera victims were left in place.

More of the Burma work force was moved into Thailand just as the outbreak was subsiding. They were able to complete the last few kilometers of the system barely on schedule in mid-OCT 43. But the end of construction did not bring an immediate end to the suffering. Beginning with the camps closest in, the POWs were slowly consolidated to Kanchanaburi. At some point in this process, ChungKai became something of a quarantine camp. POWs coming from those camps that had experienced cholera were quartered there for a period to ensure that cholera was not introduced into the main camp at Kanchanaburi. These POWs included most of the US contingent who had passed through the cholera area as they moved from Burma. No Americans are listed as dying of cholera although a few – including the Battalion surgeon CPT Lumpkin – were suspected of having had mild cases.

Work has stopped but the dying had not. Throughout the remainder of 1943, men continued to die either in those jungle camps or even at Kanchanaburi. The hospitals – such as they were – at both ChungKai and Kanchanaburi were beginning to be overwhelmed. So the Japanese established what became a true hospital at nearby Nakorn Pathom. Here for the first time proper medications and facilities were available to treat the malaria, dysentery and the myriad of other afflictions that beset these men. And still men died, but many owe their lives to the treatment they received there by the Allied medical contingent particularly the Australian doctors.

We know for certain that the last of the Americans did not reach Kanchanaburi until MAY 44. So I have termed the OCT 43 – MAY 44 period as ‘post’ construction. It was a period of transition where men were being moved towards the large camp there. It is seemingly also when the ‘follow-on’ camp at Tha Muang was established. Following the war’s end, men quickly moved from Kanchanaburi to Bangkok to begin the journey home. That is except for many of the Dutch. Because of the uncertain political situation in the DEI as it sought independence from Dutch rule, many of these men stayed at Tha Muang well into 1947. Left behind at Kanchanaburi as the now former-POWs departed were tens of thousands of romusha – mainly Tamil-Indians from Malaya – who also languished there well into 1947.

Once the consolidation of the POWs to Kanchanaburi was complete, the logistical issues were lessened. The men were at the source of the food supply. The variety and volume of the available food improved. POW life became almost tolerable again.

In the Burmese Sector many things were surprisingly similar; others not. The first 50+ kilometers of terrain were also reasonably flat and unobstructed. The Burmese romusha and AUS and Dutch POWs worked the camps up to K80-Apalaine. This is the point where the main US contingent under LTC Tharp began its TBR work in JAN 43. It shuffled between there and K105-Aungganaung for much of its time. As construction was almost complete inside Burma, the smaller Fitzsimmons group was brought up to that same area. The other POW work parties leap-frogged each other as they moved closer to the Thai border. As near as I can tell, the Burmese romusha did most of the dirt moving labor in the lower portion of the railway. The major issue was a lack of iron rails. Japanese Army units were busy in Malaya looting such rails for transport to Burma. Once they arrived, many not until 1943, the Allied POWs placed them on the prepared right-of-way. Futamatsu tells us that rails were also torn up in sections of the Burma State Railway to reuse them on the TBR.

The terrain rose somewhat more gradually into the Burmese highlands requiring no major alterations to the route nor switch-backs to allow the locomotives to pull the trains into those mountains. But there was a major difference compared to the Thai side. The Tesserine mountain range that forms that side of the border runs north and south, across the railway route. Once they reached this area, work shifted largely to bridge building. While the ‘River Kwai Bridge’ is the longest on the TBR, all the other major bridges are in Burma.

If anything, the supply conditions for the POWs was even worse than in Thailand in that there was no river running parallel to the route and the vast majority of the length of the build was through virgin jungle with no roads and little other human habitation. Unlike HellFire, there were no major cuttings in the Burmese Sector.

There are some unconfirmed reports that the first cases of cholera were noted at the K60-Taungzun camp. There are about 50 deaths due to cholera that are buried in the Thanbyuzayat cemetery but we have a defined location for only a few of them. Some of the earliest did occur at the K60-Taungzun camp. They occurred in a few weeks in MAY 43 exclusively among Australian POWs who were presumably the only ones working that area at that time. Deaths from cholera were occurring in H & F Forces on the other side of the border at the same time which leads to the questions as to whether these outbreaks had a single or perhaps multiple sources. Correctly or not, the first death from cholera was registered at the Toncha (K140) camp on 1 JAN 43. The next at ChungKai in FEB. Late-May and early-June were a particularly bad period for cholera deaths. Cholera continued to take its toll into SEP 43 on both sides of the border but those numbers were falling rapidly. While a few deaths still occurred as late as JAN 44, the worst of the outbreak was over by mid-SEP. But it had undoubtedly had a severe impact on the pace of construction with a total of just over 1000 documented deaths.

Construction proceeded in Burma more or less on schedule. The plight of the POWs obviously worsen as they moved farther from civilization but overall conditions in Burma never seemed to be as bad as those in the Thai highlands. We have an accurate count that the death toll among the nearly 700 Americans was 18%. This is just slightly lower than that calculated for the Australians and Dutch in Burma at 20-22%. Immediately, post-completion the Americans largely remained at various jungle camps assigned logging duties for train fuel. While most of the ill men were quickly evacuated to Kanchanaburi, the bulk did not arrive there until MAY 44.

Obviously the trail of bodies shifted to the Kanchanaburi – Nakorn Pathom area, but a fair number of deaths continued to be registered at the various camps across Thailand. By May 44, some men had been relocated to Nong PLaDuk and the newly established Tha Muang camp as evidenced by the first deaths being registered there. On 7 SEP 44 errant bombs from B-29 raid on the railyard killed many Dutch and British POWs. It must also be noted that after the completion date the survivors of F & H Forces were returned to Singapore. Unquestionably deaths continued to occur among those men that are not recorded or tallied as being attributable to their TBR experience.

For the record, the final death that I can reasonably associate directly with the TBR experience occurred in the Nakorn Pathom hospital on 25 SEP 45. The last registered grave was that of a Dutchman who died in Bangkok on 16 JUL 46; obviously among those who had been unable to return to the DEI. The last registered TBR-related death in the Thanbyuzayat cemetery was a British soldier who died of Beri-beri but his exact place of death was not recorded [4].

There is also a cluster of deaths mostly from malaria that are recorded as occurring in AUG 45 in POWs who had been sent south to work the Kra Isthmus Railway.

There is a rather strange grave at Thanbyuzayat that was recorded as a British soldier in FEB 46 whose cause of death is listed as “executed”. Surely there must be an interesting back-story to that episode! I am inclined to believe that he is a true post-war death but was never a POW.

For all of its horrors that earned it the name DEATH RAILWAY for which a person is said to have died for even sleeper (railroad tie) lain, as an entity the TBR is one of the most remarkable achievements of the war. [also see the above section on the Stilwell Road]

[1] Indian troops were separated from their (many British) officers in an effort to get them to join the IJA in ousting thew British from India.

[2] There are vague references to the Tadan Bridge shown in the map above as being the proposed main route and crossing point of the MaeKlong River. That apparently was changed by the senior engineer Futamatsu.

[3] Possibly in Burma; see below

[4] The re-burials were performed based on the location of the death and initial burial. Almost all of those who are buried in Burma died there.

Part 5: arrival and departure

Here are some examples of the arrival at Ban Pong and then forward movement of the POWs from Singapore:

The format became a bit jumbled in transitioning to this format (= some blank cells were deleted), but I believe that it is still readable.

| 23-06-1942 | Singapore: Changi | FMP1 | 12/1/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 1002 | JP 3,4,5 | ||

| to KL then they traveled by ship to Burma | ||||||||

| Trein 1 | 600 Eng | Trein 32 | 159 Ned | |||||

| 25-06-1942 | Singapore: Changi | FMP2 | 383 AUS | |||||

| 546 USA | ||||||||

| Trein 2 | 600 Eng | |||||||

| 27-06-1942 | Singapore: Changi | FMP3 | ||||||

| 12/1/1943 | Kanchanab 50 (l) | |||||||

| Trein 3 | 600 Eng | |||||||

| 29-06-1942 | Singapore: Changi | FMP4 | Kinsayok 171 | |||||

| Trein 4 | 600 Eng | Hindato 198 | ||||||

| 15348 | Singapore: Changi | FMP5 | 19-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | |||

| Trein 5 | 600 Eng | Trein 33 | ||||||

| 14-10-1942 | Singapore: RValley | 650 Eng | 20-01-1943 | Tarsao 130 | ||||

| Trein 6 | Rintin 181 | |||||||

| 15-10-1942 | Singapore: Changi | 800 Eng | 20-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | |||

| KL: Poedoe Gevang | Trein 34 | |||||||

| 21-01-1943 | Tarsao 130 | |||||||

| Trein 7 | ||||||||

| 16-10-1942 | Singapore: Changi | 650 Eng | Kinsayok 171 | |||||

| 22-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | ||||||

| Trein 8 | ||||||||

| 17-10-1942 | Singapore: RValley | 650 Eng | Trein 35 | |||||

| 22-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 5 | |||||

| Trein 9 | ||||||||

| 20-10-1942 | Singapore: RValley | 650 Eng | Trein 36 | |||||

| 24-01-1943 | Tarsao 130 | |||||||

| Trein 10 | ||||||||

| 22-10-1942 | Singapore: SimeR | 650 Eng | Kinsayok 171 | |||||

| 24-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 6 | |||||

| Trein 11 | ||||||||

| 23-10-1942 | Singapore: SimeR | 650 Eng | Trein 37 | |||||

| 25-01-1943 | Konyu 166 (a) | |||||||

| Trein 12 | ||||||||

| 25-10-1942 | Singapore: SimeR | 650 Eng | Kinsayok 171 | |||||

| 26-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 6 | |||||

| Trein 13 | ||||||||

| 27-10-1942 | Singapore: SimeR | 650 Eng | Trein 38 | |||||

| 26-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 8 | |||||

| Trein 14 | ||||||||

| 28-10-1942 | Singapore: Changi | 650 Eng | Trein 39 | |||||

| Tarsao 130 (a) | ||||||||

| Trein 15 | ||||||||

| 29-10-1942 | Singapore: Changi | YP | 28-01-1943 | Kanyu 151 | ||||

| Trein 16 | 650 Eng | Konyu 166 | ||||||

| 30-10-1942 | Singapore: Changi | XP | 28-01-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 8 | ||

| Trein 17 | 650 Eng | Trein 40 | ||||||

| 31-10-1942 | Singapore: Changi | WP | 1/2/1943 | Kinsayok (a) | ||||

| Trein 18 | 650 Eng | Rintin 181 (l) | ||||||

| 15352 | Singapore: Changi | VP | 1/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 8 | ||

| 2/2/1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 19 | 650 Eng | Trein 41 | ||||||

| 15383 | Singapore: Changi | UP | Rintin 181 | |||||

| 3/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 8,9 | |||||

| Trein 20 | 650 Eng | |||||||

| 15411 | Singapore: Changi | TP | Trein 42 | |||||

| 3/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 9 | |||||

| Trein 21 | 650 Eng | |||||||

| 15442 | Singapore: Changi | SP | Trein 43 | |||||

| Kinsayok 171 | ||||||||

| Trein 22 | 650 Eng | |||||||

| 15472 | Singapore: Changi | RP | 4/2/1943 | Rintin 181 | ||||

| Trein 23 | 650 Eng | Niki-Niki 282 | ||||||

| 15503 | Singapore: Changi | QP | 4/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 9 | ||

| 6/2/1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 24 | 650 Eng | Trein 44 | ||||||

| 15533 | Singapore: Changi | PP | 6-2 Kinsayok 171 (a) | |||||

| 6/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 9 | |||||

| Trein 25 | 650 Eng | 8/2/1943 | ||||||

| 15564 | Singapore: Changi | OP | Trein 45 | |||||

| 19-2 Non Barad 96 | 625 | |||||||

| Trein 26 | 650 Eng | 8/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 9 | |||

| 15595 | Singapore: Changi | NP | 9/2/1943 | |||||

| Trein 46 | ||||||||

| Trein 27 | 650 Eng | 8-2 Tamarkan 55 | ||||||

| 15625 | Singapore: Changi | MP | 9/2/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 9,10 | ||

| 10/2/1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 28 | 650 Eng | Trein 47 | ||||||

| 15656 | Singapore: Changi | LP | Taruna 26 | |||||

| 19-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 625 | JP 10 | |||||

| Trein 29 | 650 Eng | |||||||

| 15686 | Singapore: GreatW | 650 Eng | Trein 48 | |||||

| 21-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | JP 15 | |||||

| Trein 30 | ||||||||

| 13-11-1942 | Singapore: GreatW | 650 Eng | Trein 49 | D-force | ||||

| 22-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 31 | ||||||||

| 31-12-1942 | 20000 all Eng | Trein 50 | ||||||

| 23-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 51 | ||||||||

| 24-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 52 | ||||||||

| 25-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 53 | ||||||||

| 26-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 54 | ||||||||

| 27-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 55 | ||||||||

| 28-03-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 555 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 56 | ||||||||

| 18-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 560 | D-force | |||||

| Trein 57 | ||||||||

| 18-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | JP 10,11,14 | |||||

| 19-04-1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 58 | ||||||||

| Takanun 218 (l) | ||||||||

| 19-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | JP 10,11,14 | |||||

| Trein 59 | ||||||||

| 20-04-1943 | 28-4 Kinsayok (l) | |||||||

| 2-5 Takanun 218 | ||||||||

| 20-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | JP 11,12 | |||||

| Trein 60 | ||||||||

| 22-4 Kanchan 50 (l) | 600 | |||||||

| 26-4 Tarsao 130 | ||||||||

| 29-4 Kinsayok 171 | ||||||||

| 21-04-1943 | 30-4 Rintin 181 | |||||||

| 1-5 Kuye 190 | ||||||||

| 22-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | JP 11,12 | |||||

| Trein 61 | ||||||||

| 23-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | JP 11,14 | |||||

| Trein 62 | ||||||||

| 24-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 63 | ||||||||

| 25-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 64 | ||||||||

| 26-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 65 | ||||||||

| 27-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 66 | ||||||||

| 28-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 67 | ||||||||

| 28-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 68 | ||||||||

| 29-4 ThaMa Kam? | 600 | |||||||

| 30-4 Kanchanb 50 | ||||||||

| 4-5 Tarsao 130 | ||||||||

| 7-5 Rintin 181 | ||||||||

| 13-5 Takanun 218 | ||||||||

| 29-04-1943 | 16-5 Niki-Niki 282 | |||||||

| 19-5 Sonkurai 294 | ||||||||

| 30-04-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 69 | ||||||||

| 1/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 70 | ||||||||

| 2/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 71 | ||||||||

| 3/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 72 | ||||||||

| 4/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 73 | ||||||||

| 5/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 74 | ||||||||

| 10/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | F-force | |||||

| Trein 75 | ||||||||

| 11/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | H-force | |||||

| Trein 76 | ||||||||

| 11/5/1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | H-force | |||||

| 13-05-1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 77 | ||||||||

| 20-5 Tonchan 139 | ||||||||

| 14-05-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | H-force | |||||

| Trein 78 | ||||||||

| 18-05-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | H-force | |||||

| Trein 79 | ||||||||

| 18-05-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 600 | H-force | |||||

| 22-05-1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 80 | ||||||||

| Tonchan 139 | ||||||||

| 22-05-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 270 | H-force | |||||

| 29-06-1943 | ||||||||

| Trein 81 | ||||||||

| Konkoita 262 | ||||||||

| 29-08-1943 | Singapore: Changi | 230 | K-force | |||||

| Trein 82 | Med. Party | |||||||

| Singapore: Changi | 115 | L-force | ||||||

| Trein 83 | Med. Party | |||||||

| 3/2/1944 | Singapore: Changi | 30 | JP 18 | |||||

| Trein 84 | ||||||||

| 23-04-1944 | Singapore: Changi | F-force | ||||||

| Trein | ||||||||

| 4/5/1944 | Singapore: Changi | H-force | ||||||

| Trein |